Mahida flicks her hands lightly as she bobs her head back and forth. Dressed in a black, embroidered abaya, a veil and dangling gold earrings, Mahida smiles as the thin man next to her plays a long, melancholy tune on the flute. Her rich voice cracks through the small club in downtown Cairo, calling out in a Nubian dialect: "Oh sweetness be upon you Yusuf, my candles are lit. Father, our home is full of the sleepless."

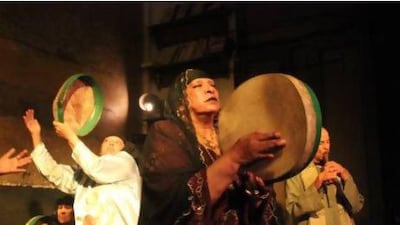

Behind her, three women and two men strike water-buffalo skins stretched across wooden frames. As the music builds to a crescendo, the audience is captivated as one of the female drummers steps forward, hopping quickly from foot to foot, hoisting her drum into the air and striking it forcefully.

There is no microphone or stage. The audience sits on cushions, partially encircling the group. The Mazaher ensemble is performing the ancient practice of Zar music.

Considered a healing rite, the Zar is one of the only forms of traditional Egyptian music where women play the lead role. And on stage, Mahida runs the show.

It is an energetic, polyrhythmic style of music originating from the border between Egypt and Sudan, and it possesses a distinctly African sound. Though it is still practised in East Africa and some Gulf countries, in Egypt the Zar is on the verge of extinction.

Historically, the ritual is believed to placate jinn, or spirits, that harm participants' mental health. As a rite, the music and trance-like dancing that accompany Zar are meant to be a release of tension and stress for women. For Mahida, its value in the modern world is simple: "People need to get this stuff out of their hearts."

Each week, the Zar musicians gather at Makan, a venue devoted to preserving and archiving Egypt's folk music.

"Zar is a very old music that was kept away from any light and ignored by the state. It's always been underground and so it remains unique in its music and melodies," says Ahmed El Maghraby, the founder of the Egyptian Centre for Culture and Art, which runs Makan.

Music experts have long criticised the Egyptian government for neglecting the country's folk music. Worried that this centuries-old music was vanishing, El Maghraby has spent years documenting the performances of Mazaher and others from Upper Egypt, where the music was originally popular.

Of this once-thriving art form, Ahmed estimates that fewer than 25 performers remain today. Mahida places that number even lower, saying that only about 10 women remain who can perform the vital healing ritual that comes with the music.

"I've learnt from my mother, but my voice is something from God," says Mahida. "We all inherited the music from our families. I learnt from my mother, my mother from my grandmother, it's something that's passed down generation to generation."

Mahida, whose sole profession is performing Zar, began practising when she was 11 years old. The songs she sings are the same ones her grandmother sang. They are the songs of African slaves brought into Egypt centuries ago. Each song possesses its own rhythm and is sung to a different spirit. But the Zar gatherings act as a vital form of expression for women in conservative, strictly patriarchal rural communities, according to the folk music expert Zakaria Ibrahim.

"In the past, men could meet in coffee houses and spend hours but women couldn't," says Ibrahim, "For women in a Muslim country, the Zar acted as a kind of woman's club, where they meet each other and speak about mutual suffering."

While many Egyptians are familiar with Zar, Mahida says its often misunderstood because it is portrayed in movies and on television as a form of black magic and exorcism. The country's conservatives have denounced it as un-Islamic, while many take issue with the prominent role women play in the ceremony.

All of that changes once people hear the music, says El Maghraby. "There are a lot of Egyptians who discover this Egyptian dimension to the music. There's an exchange of energy in these small shows that keeps the intimate relationship of Zar intact."

Though the rite is still practised in Cairo, widespread interest in it has died out. Thirty years ago, it would have been easy to find a Zar performance in Port Said or the Delta region. Now, Ibrahim says, it is rarely performed outside the capital city. There is little interest from the next generation to take up the family craft, and Mahida is aware that Zar may vanish in Egypt.

"I do have children, but they aren't interested, and we're the last people playing Zar and the generation afterwards just isn't interested at all, it will go with us when we stop playing."

Though the ritual of Zar may end with Mahida's generation of performers, El Maghraby hopes Makan can keep this unique music from disappearing altogether.