On Thursday night, the Israeli commercial vessel Helios Ray suffered four explosions, two on each side of the hull, above the waterline. The stricken vessel was forced to head to the nearest port, Dubai.

Capt Ranjith Raja of the data firm Refinitiv told the AP that the Israeli-owned vessel had left the Arabian Gulf on Thursday bound for Singapore.

On Friday at 2:30 GMT, the vessel stopped for at least nine hours east of a main Omani port before making a 360-degree turn and sailing towards Dubai, likely for damage assessment and repairs, he said.

It is now thought that commandos of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard mounted a sabotage operation on the vessel.

"This was indeed an operation by Iran. That is clear," Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told Kan radio.

Initial Israeli assessments suggested that the ship had been hit with missiles, but Security Cabinet Minister Yoav Gallant, who was formerly a commander in the Israeli military, later told news outlet Ynet that "Iranian commandos" had carried out the attack using limpet mines.

This was also the assessment of Israeli inspectors who examined the ship in Dubai.

Security analyst Charles Lister also concluded that limpet mines were used in the attack, based on photos of the damage.

It appears the ship, which was delivering cars to the region, had been specifically tracked and singled out, with devices placed above the waterline, an echo of the Fujairah tanker attacks in the UAE in 2019.

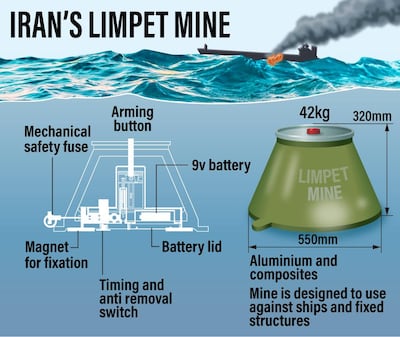

But what is a limpet mine?

In essence, it is an explosive device that can be stuck to a ship and then detonated.

It is designed to be used by frogmen or swimmers who approach an enemy vessel from below and then fix the bomb to the underside of the ship.

It will have a timer or a trigger so it will detonate when the divers are a safe distance away.

The mine gets its name from the small molluscs that attach themselves to rocks.

There are numerous variations of limpet mines employed over the last several decades but modern ones usually use magnets to stick to the side of a ship.

Once the diver has attached their charge, they can set the timer, usually delayed by a mechanical or chemical fuse. Some include a secondary anti-tamper mechanism to make them harder to remove.

Most are not designed to destroy the ship.

The relatively small explosives – the swimmers need to be able to carry the devices some distance – are intended to be placed in critical locations that will disable rather than sink the vessel.

These include the rudder, propellers, shafts and anything else that lies below the water and which the ship needs to move.

But they have also been used to scupper a ship by blowing a hole in the side.

However, the issue here for military targets is that warships are, by design, meant to withstand battle at sea and their armoured hulls are hard to penetrate.

By contrast, the impact on a commercial vessel, such as a tanker or cargo ship, can be significant.

What can ships do about limpets?

Military harbours will often have access restrictions or cordons and measures to enforce them, such as anti-diver netting, infrared or ultrasound detectors.

Most navies also keep lookouts on deck, checking for signs that divers are approaching the vessel underwater. If they believe they spot something, US Navy personnel are reportedly authorised to drop a concussion grenade into the water.

These cause a sound wave that on land will disorientate a person but underwater can kill a nearby diver.

Then they call an Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) team. These EOD divers will then check the underside of the vessel for any sign of a device.

The US has teams permanently stationed in Bahrain.

Many countries restrict the sale of the equipment needed to build and use limpet mines – meaning most of such attacks are carried out by states.

Limpet mine attacks quite are hard to stop if the ship is stationary, especially on commercial rather than military vessels, but a moving target is harder to catch and affix the explosive.

Any famous cases of limpet mines being used?

Yes, several. But not many are from the last few decades – and they are not as widely used as movies might have you believe.

In one famous raid during the Second World War, an allied Z Special Forces unit – a combination of British, Australian, New Zealand, Indonesian, South African, Dutch and Timorese soldiers trained in covert attacks behind enemy lines – sunk six Japanese ships in 1943 while they were in Singapore harbour.

Sneaking in on a converted Japanese fishing vessel, they paddled into the harbour and then placed the mines on tankers and cargo ships. The incident took the Japanese by surprise and they ruled out a foreign attack as so implausible that instead, they blamed local saboteurs.

More recently, French overseas intelligence force used a limpet mine to sink the Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior – used most famously by the activists to disrupt commercial whaling – while in port in Auckland in 1985, killing one person.

The scandal eventually led to the resignation of French Defense Minister Charles Hernu.