Nicole Condrey met her husband Ron while jumping out of a plane.

She was working to earn her skydiving licence in 2013 and brought her brother along for a jump. Mr Condrey, a Master Naval Parachutist and a tandem instructor, was strapped to the back of her skydiving-newbie brother.

“Ron was like, can I ask her out on a date? And my brother's like, ask me again when we get to the ground,” Ms Condrey laughed.

“He did such a good job of talking [my brother] through that whole event that when we got to the ground, my brother essentially offered my hand in marriage to Ron.”

But beneath that calming presence, Mr Condrey was battling silent turmoil that all too many veterans share.

Seventeen US veterans die by suicide every day, according to 2019 figures — and Mr Condrey was one of them.

A decorated US Navy Special Warfare veteran who worked as an explosive ordnance technician over 14 deployments to Afghanistan, Somalia and elsewhere, Mr Condrey, who died in 2018, had been struggling with a service-related traumatic brain injury and an ensuing mental health decline.

The post-9/11 years saw veteran suicide rates skyrocket by an average of 47 more deaths per year between 2001 and 2018.

Younger veterans returning home from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and other conflicts from America's Global War on Terrorism bore the brunt of that deadly spike, with the suicide rate among soldiers aged 18-34 rising by 95.3 per cent.

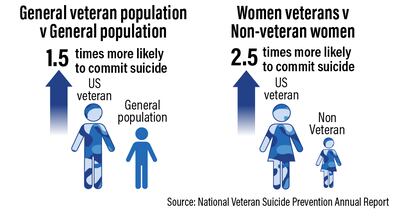

Veteran suicides are also increasing at a greater rate than that of the general US population, though they mirror a general rise.

A majority of veterans who died by suicide in those years had not had interactions with or received treatment through the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

“I think often people assume that all veterans come to the VA health system for care, but they don't. The minority of veterans come to the VA for care,” John McCarthy, director of data and surveillance at the VA's Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, told The National.

He said it was “discouraging to see rates increase year after year” but added that he believes the department “has done a tremendous job with suicide prevention initiatives”.

Several people emphasised to The National that the VA system is not user-friendly.

Joan Hampton is a licensed professional counsellor in Gulfport, Mississippi, where she works with the community's large veteran population. She said many clients come to her after attempting to get care through the VA, which failed to meet their specific needs.

“They're assigned a diagnosis of something that is really low level, like adjustment disorder with anxiety, when these people come back with real trauma and they should have the diagnosis of PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder],” Ms Hampton told The National.

She added that many of her clients were “seeing [therapists] for general issues” through the VA, but did not receive specialised expert care for PTSD.

A representative for the VA told The National that the department has provided training and consultation to competency to 7,519 unique providers in Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), and has 125 PTSD Clinical Teams nationally who focus on providing specialty care.

Ashley Dwyer, a US Army veteran of the Iraq war, now works with a mental health coaching group.

She said that there are persistent cultural problems in the military around mental health, pain and trauma, in addition to structural hurdles with the VA.

“I think that this mentality that you're raised within the military, where ‘pain is just weakness leaving the body’, makes it really hard to address mental and emotional pain … there's almost a flavour of shame that comes with it,” Ms Dwyer told The National.

Her journey from the military service into mental health care began when she first returned from Iraq at 19 years old. She was greeted by Vietnam War veterans at the airport.

“That just made such a huge impact on me … It also put this cautionary tale in my head, about needing to stay on top of my mental wellness because so many of the veterans before me struggled.”

Brianne Sampson, director of clinical support and emotional wellness at veterans' organisation Hope for the Warriors, said challenges such as integrating back into the workforce are especially hard for veterans of America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“[They] have been in life-and-death situations and can find some of the office politics or employment policies challenging when comparing them to the severity of situations experienced in combat,” Ms Sampson told The National.

Joshua Sooklal, a former navy medic who suffered several traumatic brain injuries while deployed in the Middle East with the Marines, agrees.

“In the military, their ‘job’ was connected to the survival of their brothers and sisters on their left and right. When they leave the military, they take on jobs that pay the bills … and miss a sense of purpose,” Mr Sooklal told The National.

He now works as a military and veterans' programme manager for Hope for the Warriors, engaging with fellow veterans on mental health issues.

Mr Sooklal added that transitioning servicemembers are taught how to conduct a job search, complete a resume as well as VA benefits and disability forms, but are lacking the “mental or emotional preparation needed” to transition to civilian life.

Although the struggle for many veterans endures, there are some signs of progress.

From 2019 to 2020, there were “unprecedented” veteran suicide reductions for the first time since 2001, according to the VA's 2022 report. The general suicide rate declined in those years, too.

In January, the VA expanded healthcare access for veterans in acute suicidal crises. Now, veterans can go to any VA or external healthcare facility for emergency care “at no cost”, whether or not they are enrolled in the system.

“The VA wants to prevent suicide for all veterans, not just those in the VA. So this is a really exciting development,” Dr McCarthy said.

He added that even the existence of his position is a show of progress.

“Now we have a very established process for compiling information … and that data has allowed us to have the annual report, and lots of other reports within VA that has led to a lot of suicide prevention initiatives.”

For Ms Condrey, her late husband continues to help veterans.

She recently shared her and her late husband's story at a veterans' group event in Ohio, after her speech a veteran in attendance told her that he had gone skydiving on “one of the worst days of his life” — his wife was divorcing him and his best friend had died by suicide.

As he scrolled through his mobile phone trying to find a picture of his skydive, the veteran told Ms Condrey that his partner “saved his life” that day by listening to his experience and sharing his own.

When he found the picture, it was Ron.

The military taught many veterans that “pain is weakness leaving the body”, but Ms Condrey said her husband taught her that the greatest shows of strength come dressed as vulnerability.

“Ron was the first one to go into a group of veterans who were struggling … talk to them, and then break down in tears and tell them 'I'm struggling, too,'” she said.

“Ron was the epitome of showing other people that he wasn't a rock to lean on. We want to be that rock for people. They're going through some hard time, 'I'll be that rock for you'.

“Well, rocks aren't comfortable to lean on … and if you're willing to open up and tell people that you're also struggling — that is half the battle, because now people know it's OK to feel that way.”

!['We need to give these veterans credit for the struggle that they went through before this happened and not put the blame on them ... Don't you dare be mad at him [for dying by suicide], he did it as long as he physically and mentally could,' Ms Condrey said](https://www.thenationalnews.com/resizer/v2/3YL7QMIJVRGFJJWJ6WGSGEEAH4.jpg?smart=true&auth=255a894c98f47384a4df5bf00e29748626b6e82814eacc989700cd29c5851d3d&width=400&height=225)