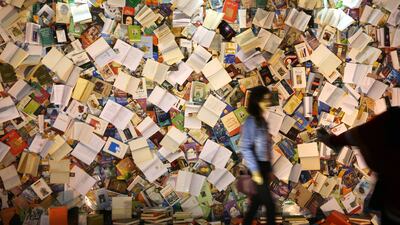

As pupils in the US head back to school this month, they might notice something different about their libraries: more books have been banned and reading restrictions have increased.

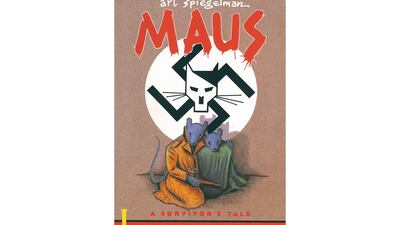

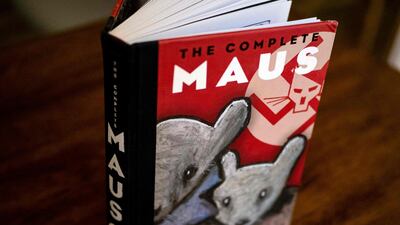

Earlier this year, a Tennessee school district stirred controversy after banning Maus, a Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel that tackles the horrors of the Holocaust — though a Texas school district reversed a decision this week to ban Anne Frank's Diary: The Graphic Adaptation from Israeli filmmaker Ari Folman after international criticism.

The scope of school book and library policing in a country that positions itself as a beacon of free speech is “wildly unprecedented”, said Patrick Sweeney, political director of EveryLibrary, a non-profit organisation and the only political action committee for libraries in the US.

From Pennsylvania to Florida and Arizona, a number of districts in almost half of US states have presented bills that codify forms of book-banning. In the past two years, six states have passed laws that mandate parental involvement in reviewing books, with five more considering similar policies.

And “thousands” of books could be affected, EveryLibrary reported.

“There's never been anything like this before,” Mr Sweeney told The National.

“There have been have been occasional attempts to legislate book-banning and codify book-banning into law to regulate what Americans are allowed to access, but nothing that's this orchestrated.”

Many of the state and local bills aim to create strict requirements regarding the materials that are allowed in classrooms or school libraries, and have required districts to post instructional materials online so that parents know how to submit objections to content.

In Tennessee, for example, a new law gives a politically appointed commission authority to issue blanket bans on books and also gives the state's textbook commission the task of creating an appeals process for challenged books if a pupil, family member or school employee disagrees with a decision made by a local board.

Tennessee teacher Sydney Rawls went viral on TikTok recently when she described the impact the law has on teachers and school libraries, as she catalogued the hundreds of books she keeps in her classroom.

She described the frustrating reality of having to tell pupils they are not allowed to read books until she has completed logging and submitting all of her classroom reading options for approval.

“The kids want to read books,” she said. “The kids in here are asking me, 'can I go get a book and read', and they're so excited. And I have to say, 'no, you can't because I haven't had the chance to go through … to catalogue them'.”

More than 1,100 kilometres away, Florida science teacher Emily Jones empathised with Ms Rawls. New legislation in her state, pushed by far-right Governor Ron DeSantis to “combat wokeness” in the classroom, requires school districts to have all reading and instructional materials reviewed by a district employee with a “valid educational media specialist certificate”.

“There's constantly books being presented to the school board to be banned. They haven't officially banned any yet, but there's constant scrutiny,” Ms Jones told The National.

“We have to be very cautious about what we have on our personal bookshelves. That's probably the more stressful part for a classroom teacher. I can't imagine how language arts teachers feel.”

A majority of the top 10 most challenged books in the past year have been “sexually explicit”, have concerned LGBTQ issues or have been written by authors of colour, the American Library Association reported. Among those considered “sexually explicit” for example, is Toni Morrison's classic The Bluest Eye, which grapples with the trauma of racism and childhood abuse.

A sponsor of the Tennessee legislation, state senator Jack Johnson, said his bill was passed with support from legislators, parents and community leaders.

“As a former teacher myself, I kind of like the idea that it provides a degree of protection for that teacher,” Mr Johnson recently told local media. “Those materials that are in the classroom have been made publicly available and parents and other stakeholders can see what is in the classroom.”

There is evidence that the impact of some of these policies is seeping into even basic reading materials. A Florida district drew national attention this week after it rejected a donation of dictionaries to its library because of a new book-freeze policy enacted to comply with the DeSantis law.

School officials told local news in Florida that this is because the law requires all reading material in schools — donated or purchased — be “selected” by a certified education media specialist. The district does not currently have any of these specialists working in its schools.

For Mr Sweeney, the laws do nothing to enhance parents' ability to make decisions about age-appropriate books for their children because those systems are already in place.

“Not a lot of Americans knew that they always had control over what their children checked out from school, their public library,” he said.

“I started as an elementary school librarian. At any time, parents could come in and tell me what they felt was appropriate for their child and not appropriate for their child.

“We're seeing public outcry about something that there's already been a solution for.”