Leading analysts have told a Chatham House panel that America's changing foreign policy priorities have led to countries in the region working more closely with Beijing.

“For China itself, the United States' strategic contraction from the region is a problem, not a privilege, for China,” said Zhang Chuchu, assistant professor of international relations at Fudan University.

“We need to take consideration of the local powers, for instance Saudi Arabia or the Emirates. We have to look at all those regional powers as aspirational political actors.”

Ahmed Aboudouh, associate fellow of the Chatham House Middle East and North Africa Programme, said the Belt and Road Initiative was something that expanded Beijing's appeal to regional countries, in addition to strong trade ties.

“I think Middle Eastern countries do not see China's increased engagement with the region as something new per se but it has been intensified since Xi Jinping came to power,” he said.

“Middle Eastern countries have received this increased interest by China in the Middle East by strategic hedging. They do not want to be the battlefield of great power competition and they want to maximise their opportunities from both from both sides and I think Middle Eastern countries are enjoying strategic autonomy.”

Ms Zhang said the Gulf countries were able to cultivate ties with both sides, even with increased competition between Beijing and Washington.

“They are trying to use this big power competition as an opportunity to hedge between different powers and maximise their own interests,” she said. “They know very well that if they just sign with China and they leave the United States, then it's not in their own interest.

“You can see that although there is competition between both sides, the competition is asymmetric competition – for instance, China is promoting unmanned, unmanned drones in the region, which is a market that the United States doesn't want to open. So it's not that China is going to confront the United States directly.”

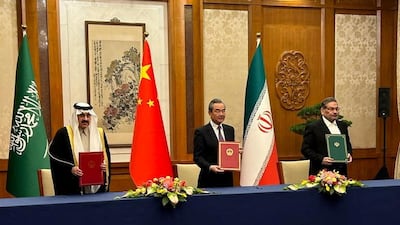

The announcement that China had been involved in rapprochement talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia earlier this year marked a gear shift for the Chinese diplomatic profile in the region.

“We can talk about the broader role that China wants to play in the Middle East and mediating this specific deal was I think a big success for China,” said Mr Aboudouh.

“China now is being seen as a trusted partner – a partner who is interested in stability, in de-escalation and wants to be friendly to powers in the region and take these powers into consideration.”

He added that the development challenge was a fundamental pillar of western foreign policy in the region.

“I think also that China's negotiation of this deal changed the long-held western conviction that denuclearisation north of Iran is a prerequisite for normalisation with its Arab neighbours.”

Dawn Murphy, associate professor of national security strategy at the US National War College, said specific countries' pursuit of co-operation with China carefully balanced their own interests.

“I would see the Emirates as the leading edge, whether it's health co-operation or artificial intelligence or digital,” she said.

“The UAE is a good example of the ways in which many Arab Gulf countries are using their development strategies to [pursue] their vision of what they want to be in the longer term and how that really complements China's approach to the region.”