The palm-sized sculpture of a boat will highlight the movement of people throughout history at London’s British Museum at the opening of Refugee Week.

The boat made of reclaimed metals and wood symbolises the journey to Europe made by migrants across the Mediterranean as they flee wars in the Middle East, Central Asia and West Africa.

A piece of bicycle mudflap has been folded and welded to look like a fishing boat. Inside, matchsticks burnt at the tip appear like migrants, huddled together as they make their cold and dangerous sea crossing.

Syrian-born, Cambridge-based artist Issam Kourbaj, donated the work to the museum and described it as a “humble gesture” reflecting on global migration. “It's not only about Syrian refugees. It is about many refugees of ecological, economic political causes,” he told The National.

More than 82.4 million people have been forced to flee their homes, more than ever before. One in 95 people – over one per cent of the world’s population – is displaced.

Yet migration and refugees will be an issue for humankind, said Kourbaj. “I don't think that at any time historically the idea of refugees ever stopped, because its [part of] life. The word refugee can have many different meanings.”

He points to the world’s oldest known refugee, King Idrimi, who fled Aleppo around 3,500 years ago, with his statue housed at the British Museum. The limestone statue of the King, which he commissioned of himself, includes cuneiform carvings of his own life.

His new work, Precarious Passage (2016-2023), is part of a continuing series which he began in 2016 and saw the creation of a flotilla of over a thousand small boats, which he has presented alongside installations, performance and text.

The original series was dedicated to the millions of Syrians fleeing brutal attacks on civilians after the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011.

It soon came to encompass the global migration to Europe. “European colonisers interfered with the world, and the world became poorer. The only resources now are in Europe,” he said, “When Europeans travel abroad, they are called explorers, but when it's the other way round, it is labelled in a negative way.”

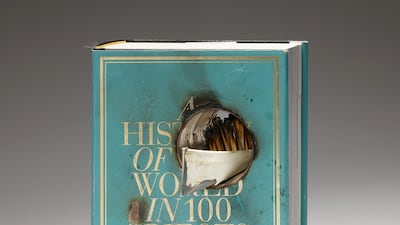

In this new iteration, the boat appears through a large hole that was drilled into the copy of the British Museum’s A History of the World in 100 Objects. It is a nod to former museum director Neil McGregor’s naming of Kourbaj's boats as the 101st object to encapsulate our modern age, in 2020.

Hartwig Fischer, director of the British Museum, said the work would be presented for the first time to mark refugee week, “Issam Kourbaj’s Precarious Passage highlights the challenges people are facing who seek refuge from violence and poverty throughout history.

“I am grateful to him for the gift of this artwork,” said Fischer.

“The Museum continues to support Refugee Week and its aim to promote awareness around the hardship of being displaced today as well as the creativity and resilience of refugees,” said Fischer.

Boats are an important metaphor for migration, said Kourbaj: “Metaphor means to cross over. Just like a boat is transporting you from one place to another.”

The artist came to the UK in the 1990s, to study theatre in design. As an art student in Damascus in the 1980s, Kourbaj was fascinated by the boat makers of Syria’s island of Arwad, whose ageless woodcarving craft is said to have existed since the Phoenicians. “I used to go there and draw them,” he said.

Decades later, he came across a 2,300-year-old miniature lead model of a boat carrying three goddesses, housed in Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum. The ancient sculpture that was excavated in Tartus is an important reminder that anyone can be displaced. “This is how Syria sent goddesses across the Mediterranean in the past,” he said.

While researching his series, Kourbaj visited refugee camps on the Isle of Lesbos in Greece in 2016 and met Syrian refugees in the UK on the Isle of Bute in Scotland in 2019.

The artist questions the government’s handling of migration, where asylum seekers are threatened with deportation to Rwanda. “In our culture, somebody knocks at your door, you open the door. You don't close the door in their face or lock them in the basement.”

Refugees to the UK had real reasons to be here, he added. “I doubt that anybody would leave their own country just for the sake of leaving if we don’t have a reason to leave.”

He hopes the work will highlight the need to treat refugees with more dignity. “People who were forced to migrate forced to migrate [need] an ear to listen to, to respect their human rights,” he said.

“They need to be respected, regardless of where they are coming from.”