For thousands of years, the Mediterranean’s perilous maritime route along the Skerki Bank has been of major strategic importance for conquerors - and a treasure trove for looters.

It is a watery graveyard for hundreds of vessels sunk during battles from antiquity to modern times or come to grief in the relentless opposing currents and menacing series of rocky elevations hidden just below the surface.

Now, the area bordered by Sicily in the north and the Tunisian coast to the south-west, has yielded some of the secrets in its depths to an international team of underwater archaeologists.

In the largest and most ambitious international mission ever conducted under the auspices of Unesco, experts from Algeria, Croatia, Egypt, France, Italy, Morocco, Spain and Tunisia mapped an area of seabed 10km square in an effort to study and protect their shared underwater cultural heritage.

Two robots and multibeam sonar were used to document the remains of six shipwrecks dating from ancient times to the 20th century, three of which were previously unknown.

The multilateral team for the mission, which has been four years in the planning, finally came together for two weeks last year and on Thursday they unveiled their findings.

“Underwater heritage is very important," Unesco archaeologist Alison Faynot told The National. "You think it is extremely protected and unreachable and yet it is quite fragile, and just a change in the environment or seabed can have a very dangerous impact on it.”

“People see underwater cultural heritage as a treasure and something to collect, but it is really significant. All its little details give us so many clues about where we come from.

“In the Mediterranean, it shows why it means so much since eight countries are involved and have come together because they want to share the heritage.

“Underwater cultural heritage is not a treasure, it is vulnerable and because of it we really need to protect it and educate people in protecting it.”

The group's mission consisted of two standalone projects that were focused on conducting a thorough study of the Skerki Bank on the Tunisian continental shelf as well as following in the footsteps of the American archaeologists Robert Ballard and Anna Marguerite McCann in the Sicilian Channel.

It was while undertaking a full-scale survey of the ocean floor around the Keith Reef, a particularly hazardous zone of the Skerki Bank, that they discovered three previously unknown wrecks: one, believed to be a merchant vessel dating as far back as the 1st century BC; and two, a metal vessel and a wooden vessel, from the late 19th or early 20th centuries.

The archaeologists used a robot called Hilarion, which spent 18 hours under water, to verify and document the targets of the newly mapped area, and multibeam sonar garnered more information about the area.

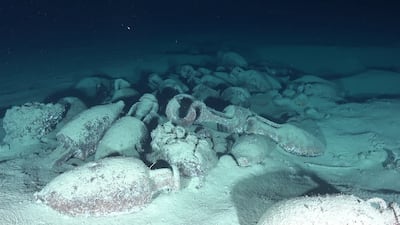

Three Roman wrecks discovered on the Italian continental shelf during the Ballard-McCann expeditions from the 1980s to 2000 were also documented in high-resolution images by a robot called Arthur, weighing less than 80kg, with powerful lights and capable of going 2,500 meters deep.

Such underwater heritage is vulnerable to exploitation, trawling and fishing, trafficking and the impacts of climate change, which is why the mission's aim was to demarcate the precise zone in which many shipwrecks lie, and to document as many artefacts as possible.

Following on from the framework of the 2001 Unesco Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage for areas outside territorial waters, the project was originally launched in 2018.

"We have had eight countries working together to protect shared heritage," Ms Faynot said.

"We chose these areas as the first because Italy came to us in 2018 and notified us about some of the wrecks. It is a very dangerous area and we wanted to protect the wrecks there. It was dangerous for the robot ... we had to hope it did not get stuck.

"The robot can grasp items and blow air on to it and push the sediment away so we could see what is there.

"The mission was possible due to France giving us access to its ship and robots which can go really deep. The technology available made it possible for us to do this work."

Together, the two robots filmed 400 hours of video footage and took more than 20,000 images.

Archaeologists found that the state of preservation of the shipwrecks and artefacts discovered by Ballard and McCann to be almost the same as nearly 30 years ago, and the new higher resolution photos and videos are helping to characterise and date the ships’ cargo.

But the three discoveries on the Tunisian shelf were cause for particular elation not only because of their very existence but also the potential they might represent for other as-yet secret archaeological remains lying on the seabed.

"When we found the new ships it was a [feeling] of relief because of all the effort we have all put in and that there are still things to learn from such a heavily looted area and that there is still something to protect," Ms Faynot said. "We just felt happiness and excitement that there is still more to learn."

"We would like to come back to these sites with another mission because there could still be more to find.

“Every step of the way has been a learning curve for us. We now need to work together to protect them. Surveys and missions are an answer, as is education in the first steps to protecting them."

The team did not retrieve objects from the ships but hope to return with more advanced technology in the future.

"The technology is slowly developing, that’s why it is so important not to retrieve and collect artefacts, we decided collectively not to do it, we have documented it so we can come back maybe with better tools," Ms Faynot said.

"We would love to go back to Tunisia and dive there and do a human survey and not a robotic one. There are many areas of the world we would like to go to next."

A documentary of their work is due to be shown in Paris later this year.