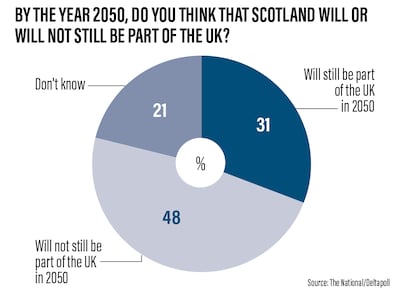

Fewer than one in three Britons believes that Scotland will still be part of the United Kingdom by 2050, The National can reveal.

Even the patriotic fervour of the mourning period for Queen Elizabeth II did not convince Britain that its destiny is to stay together, polling data shows.

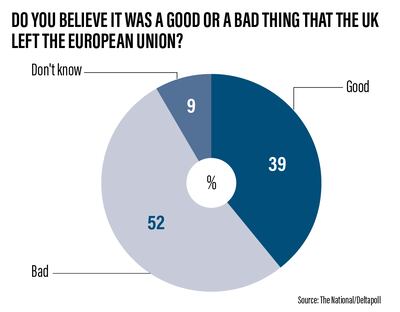

A state-of-the-nation survey by Deltapoll for The National also reveals a distinct lack of enthusiasm for Brexit more than two years after the UK left the EU, a move that changed the dynamics of the Scottish independence debate.

A narrow majority of Britons saw Brexit as a bad thing, and 46 per cent said it had gone worse than they expected, compared to only 19 per cent who were pleasantly surprised.

Asked about Scotland, only 31 per cent said it would still be part of the union by mid-century, while 48 per cent said it would not.

Opinion was more closely divided on Northern Ireland, with 46 per cent expecting it to stay in the UK and 32 per cent predicting it will leave, as nationalists gain strength on both sides of the Irish border.

Only Wales, where nationalists are a smaller presence on the political landscape, is seen as highly likely to stay put, with 61 per cent believing it will and 19 per cent saying it will not.

Other findings in the wide-ranging exclusive poll:

- A majority (62 per cent) said that relations with the Arab world must be maintained or improved.

- A majority (52 per cent) of the British public do not have confidence in Liz Truss to perform at the highest levels as a world leader

- A majority (56 per cent) said the UK had done enough to help Ukraine while 76 per cent backed the imposition of sanctions on Russia for its actions.

- A majority (78 per cent) backed global action to address the Europe-wide energy crisis

- A majority (54 per cent) wanted the UN to lead efforts to resolve the Ukraine war

- A majority (71 per cent) wanted the government to prioritise energy costs over addressing climate change challenges

- A majority (54 per cent) agreed that Iran posed a nuclear threat to the UK and the world

The poll was conducted during the first four days of mourning for the late queen, who typically spent her summers in Scotland and died at Balmoral Castle, a Highland country retreat that belonged to her personally.

In a procession highly charged with British tradition and symbolism, her coffin was taken from Balmoral to the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, then lay at rest in St Giles’s Cathedral before her final journey to London.

But people polled during those days of remembrance for the queen had little confidence that the union would long survive her, despite the brief outbreak of national pride.

“As far as attitudes to independence are concerned, it probably won’t make a huge amount of difference,” Mark Diffley, a researcher and analyst on Scottish public opinion, told The National.

“The proposition for independence does not include Scotland becoming a republic. It includes retention of the monarchy. So you can vote for independence and be a monarchist.”

The queen came to the throne in 1952 when Britain still had vestiges of the imperial might that once cemented Scotland’s place in the union, but her 70-year reign saw a growing clamour for self-government north of the border.

Her deep attachment to Scotland pushed her about as close as she ever came to expressing a political view, most notably in the last days of the referendum campaign in 2014 that ended with a No vote to independence.

Procession of Queen Elizabeth II's coffin in Edinburgh - in pictures

The queen’s guarded comment that people should “think very carefully about the future” was interpreted as a subtle nod to the No campaign, without making any explicit endorsement that would have compromised her neutrality.

David Cameron, the prime minister at the time, later had to apologise after letting slip that the queen had "purred down the line" when he briefed her on the result.

A similar coded comment came in 1977, during a time of debate over Scottish devolution, when the queen told parliament: “I cannot forget that I was crowned Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.”

Scottish nationalists have sought to make a virtue of the monarchy’s popularity, saying the 419-year-old union of the crowns would continue in an independent Scotland and highlighting the queen’s links to the country.

“Indeed, while she was everyone’s queen, for many in Scotland she was Elizabeth, Queen of Scots,” said Ian Blackford, the leader of the Scottish National Party in the House of Commons, during parliamentary tributes.

But there have long been doubts, from Scotland to the Caribbean to Australia, over whether the queen’s heirs would be able to match her popularity in countries considering loosening ties with Britain.

Mr Diffley said it was too early to assess King Charles III’s popularity in Scotland, but said the monarchy was a little less popular than in the UK at large and that younger people in particular were less enthused.

But although a good chunk of Yes voters would support a Scottish republic, it is generally a low priority and “there’s not really any votes in this,” he said.

“Even pro-independence supporters and the first minister herself would say that there will be challenges in terms of currency, trade, borders and membership of the EU. The last thing you want to do is to throw in, ‘also, by the way, we’ll get rid of the monarchy’.”

The SNP wants to call a second Scottish independence referendum in 2023 but the UK government says the question has been settled for a generation, arguing that it alone has the power to sanction such a vote.

When The National visited the historic Scottish border town of Coldstream last year, there was much despair at the thought of an international border running along the River Tweed.

"If we had voted yes in 2014, Scotland would be bankrupt right now," said Ian Fraser, 49, from Lanarkshire, a Scottish expat who lives in Dubai.

"Our annual deficit is too wide and there are never any answers on the main topics, like the five year budget forecast, the currency, how we would get back into the EU and the borders. It's quite scary, truth be told.”

But the SNP’s argument is that Brexit has effectively invalidated the 2014 referendum because Scotland voted that year, by a 55-45 margin, to remain in an EU-member Britain that no longer exists.

"Unfortunately, they got dragged out of the EU by the English. I think they have every right to have another referendum based on the new reality," said fellow expat Michael Bowles, 51.

Nationalists may be bolstered by the finding that Brexit is not proving popular. While 52 per cent of Britons said leaving the EU was a bad thing, more than six years after the referendum, only 39 per cent saw it as a good thing.

"Obviously not being part of the EU is helping our cause," said Wendy Miller, 59, an independence supporter from Aberdeenshire. "We need to secure our referendum," she said.

Ms Miller, who lives in Dubai, said she was a big supporter of the idea of an independent Scotland. “We need to secure our referendum,” she said. “Obviously not being part of the EU is helping our cause.”

The poll confirmed a strong generational divide on Brexit. While 70 per cent of millennials had a negative view of Brexit, 55 per cent of those in the baby boomer generation saw it as a good thing.

In addition, there was a lukewarm response to the bilateral trade deals touted by Brexit supporters as one of the main advantages of Britain’s economic autonomy.

Only 34 per cent said post-Brexit trade deals had been a good thing, while 43 per cent thought they were a bad thing.

“Intuitively, those who see that Brexit has overall been a good thing for the UK also harbour positive views to whether Brexit has gone better than expected and the trade deals the UK government has signed post-Brexit,” Deltapoll’s polling report said.

“They are also more supportive of focusing on building relationships with countries outside the EU and either maintaining or having a weaker relationship with the EU.”

Deltapoll interviewed 2,096 adults in Britain between September 9 and 12.