Boris Johnson’s message for the crucial second week of Cop26 was clear-cut: “Pull together and drive for the line.”

The British Prime Minister has been immersed in the climate change summit for the past week and more, making him desperate for it to succeed, not only for his own legacy but for that of the planet.

The second week of the Glasgow summit is crucial to find agreement and unity on the key areas to keep potentially catastrophic global warming in check.

After a rest day on Sunday, talks resumed on Monday with a focus on protecting people and natural habitats from the effects of climate change that it may be too late to stop.

The UK is promising £290 million ($391m) to help vulnerable countries adapt to climate shocks.

"These issues often don't get the profile they deserve but there is a lot to fight for at Cop26," said Camilla Born, an adviser to summit chief Alok Sharma.

"Lives and livelihoods are at stake. Parties have the opportunity to set a new precedent for action in negotiations."

Aside from that, negotiators are under pressure to deliver an ambitious Cop26 that addresses the urgent need to cut fossil fuel emissions, among other action.

What remains to be done to reach an enduring agreement that will mark Glasgow 2021 as the moment when the world united to save itself?

How to finish Paris?

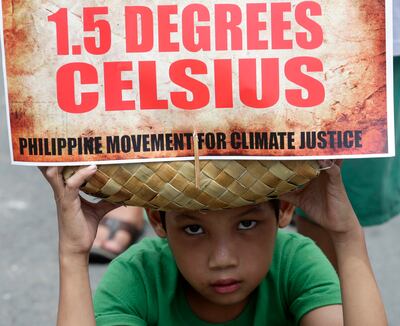

Foremost among the contentious issues will be to resolve Article 6 of the 2015 Paris Agreement to fix rules to reduce individual country emissions. States must work together to ensure the global temperature is higher that 1.5°C above that of pre-industrial times.

A deal on Article 6 is seen as crucial because it aims to promote a balanced approach to assist governments in enforcing their National Determined Contributions through voluntary international co-operation. This essentially means that by paying a price on carbon, states exceeding their NDCs would bear the costs of climate change.

But delegates have failed to reach an agreement.

Brazil and India may be willing to drop demands to count the carbon credits amassed under previous agreements in exchange for richer nations granting poor countries a share of proceeds from carbon market transactions. Until now, this was a red line for the US and the EU. But Laurent Fabius, the former foreign minister of France, said the general atmosphere had improved in Glasgow and “most negotiators want an agreement”.

But negotiators were still struggling late on Saturday to put together a series of draft decisions for government ministers to finalise during the second week.

The coming days will be vital for a breakthrough on Article 6.

How much for a tonne of carbon?

Carbon pricing has come to the forefront of policy measures as a way to reduce emissions to a level consistent with the Paris target of 1.5°C.

A higher price for carbon is seen as essential to fund the transition to net zero emissions by 2050, which is estimated to cost $44 trillion or up to 3 per cent of annual global GDP.

Tax or permit plans that try to price in the damage done by emissions create incentives to go green. So far, only a fifth of global carbon emissions are covered by such programmes, pricing carbon on average at a mere $3 a tonne.

"We haven't landed on a system yet that everyone feels can work," the UK's International Trade Secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan told broadcasters on Monday.

The International Monetary Fund has recommended a global average carbon price of $75 per tonne by the end of the decade.

But that figure should be at least $100, and right away, to reach net zero emissions by 2050, climate economists say.

The three largest emitters, China, the US and India, account for about half of global carbon emissions today and will struggle to agree the $100 a tonne mark. Negotiators are in for a tough week.

How do we demonstrate transparency?

One negotiating issue for Cop26 that remains unresolved at this late stage is transparency. Under the Paris Agreement, nations set targets on their future greenhouse gas emissions, but it is not known how these are reported nor whether they are transparent and fair.

The discussions on transparency should have been finalised last year but were postponed owing to the pandemic. Failure to get transparency right threatens to undermine any agreement to minimise warming.

Paris lets governments set their own emissions-cutting targets, with many of them are in the distant future, and verifying that countries are staying honest to their commitments and goals is tricky.

China does not like the idea of providing data in formats set by other nations. Brazil and Russia too have baulked at disclosing details on emissions-cutting targets.

Countries do not have to show internationally that they have implemented their climate promises because they have only to demonstrate progress.

This activity to report on “progress” is, therefore, the only means of keeping track on whether countries do what they said they were going to do.

There is currently a large element of trust needed for the entire system of global co-operation to work. Whether this can be firmed up into something more tangible is unknown.

What are the key dates for tackling climate change?

2023

All UK companies will have to disclose how they intend to transition to net zero, although any commitments made will not be binding.

2030

World leaders representing 110 nations have signed a declaration to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030. They account for 85 per cent of forests globally, and include Brazil, Colombia and Democratic Republic of the Congo.

2030

Ninety countries have agreed to cut their methane emissions by 30 per cent by 2030 compared with 2020 levels. The pledge, was signed by more than half of the world’s top 30 methane emitters, but not by China, Russia or India.

A so-called Breakthrough Agenda also aims to drive down the cost of sustainable solutions such as electric vehicles, green steel and hydrogen production by 2030.

2040s

While rich countries agreed to phase out coal power in the 2030s, the 2040s will be the moment when the rest of the world shuts down coal power stations.

The fossil fuel is the single biggest contributor to climate change, with coal-burning energy plants a major source of greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution.

For the first time, major users including Poland, Vietnam and Chile agreed they will no longer build or invest in new coal power.

2050

The core aim of Cop26 has been to reach a consensus on actions to secure net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

The world’s biggest banks and institutions have also confirmed that they will be aligned with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

2060

China’s date to hit carbon neutrality with a promise to end peak emissions before 2030.

2070

The date that India will belatedly meet net-zero emissions. While the promise is 20 years later than the 2050 goal, it is the first time that India has set such a target. The country, the world’s third-biggest emitter of carbon dioxide, has promised to source half of its energy from renewables by 2030.

2100

The International Monetary Fund estimates that unchecked warming would slash 7 per cent off global output by 2100. The Network for Greening the Financial System group of world central banks suggests it could be as high as 13 per cent.