Of all the unintended consequences of the September 11 attacks, the collapse of Britain’s Labour Party is probably one of the most important and least foreseen.

On 9/11, the disintegration of Labour would have seemed unimaginable. Three months before the destruction of the World Trade Centre, the Labour Party had been led to a second landslide victory by Tony Blair. Yet today, the party has been out of power for more than a decade and faces many more years in the wilderness before it has a realistic chance of returning to government.

“It changed the way Britain was governed,” says Bronwen Maddox, director of London’s Institute for Government think tank.

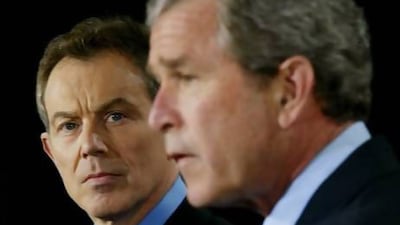

The march to Labour’s catastrophe began only nine days after the Al Qaeda attacks. On September 20, 2001, then-president George W Bush addressed a joint session of Congress to outline America’s response. The only foreign leader in the US Capitol that evening was Mr Blair.

To loud cheers, the president gave him a shout out: “I'm so honoured the British prime minister has crossed an ocean to show his unity with America. Thank you for coming, friend.”

On that same day, at a White House dinner, the outline of the coming military action in Afghanistan was discussed along with one other intervention: removing Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq.

Sir Christopher Meyer, the British ambassador to the US at the time, attended the dinner and later told reporters Mr Blair gave no indication that regime change in Iraq would be a problem.

His acquiescence was hardly surprising.

In April 1999, the prime minister had given a major speech in Chicago, in which he said: “War is an imperfect instrument for righting humanitarian distress; but armed force is sometimes the only means of dealing with dictators.”

He mentioned two dictators by name. One of them was Saddam Hussein. The other was Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic. As Mr Blair delivered the speech, Nato planes were bombing what was still called Yugoslavia, including its capital Belgrade, to force Milosevic to remove his troops from Kosovo. The bombing campaign was successful.

Robin Lustig, who at the time was one of the BBC’s main news presenters, points out: “Blair’s history in his first three years in office was one of co-operating with American presidents and having success: the Good Friday Agreement and Kosovo [with Bill Clinton] and then Afghanistan. This profoundly shaped his view of how to use power.”

Mr Lustig says the former prime minister shared “a quasi-messianic worldview” with Mr Bush.

“He felt he had been put on Earth to fight evil.”

The former BBC man recalls, “I interviewed him and asked, ‘What do you say to people who call you Bush’s puppet?’ Blair answered, ‘It’s worse than that, I agree with him.’”

In any case, after the September 20 meeting, the events were now linked: the 9/11 attacks, and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

“The invasion of Iraq was tragic,” says Ms Maddox.

“It profoundly changed Blair’s premiership. If Iraq hadn’t happened, Afghanistan would have gone so much better.”

Ms Maddox points out a deeper consequence of linking Afghanistan to Iraq.

“Iraq subverted his domestic agenda. It allowed the Labour Party to turn on Blairism,” she says.

Mr Lustig agrees. The Labour Party rank-and-file membership really wasn’t aligned with Mr Blair’s worldview.

“There were two main streams to the Labour Party: anti-Americanism and a socialist, almost pacifist strain. Blair was not a socialist and he was pro-American.”

But the man knew how to win elections and electoral victories can paper over a lot of cracks.

Even after it became clear that the American and British occupation of Iraq was heading for failure, Mr Blair won a third election in 2005, with a working majority of 66.

When he stood down in 2008, fulfilling a long-standing agreement to let Gordon Brown become prime minister, he went without a word of apology for following Mr Bush into Iraq and Afghanistan. Both conflicts were continuing and clearly had not succeeded.

Mr Blair and all those associated with him became poison to many in the Labour Party.

The Labour Party without Mr Blair at the top became poison to press baron Rupert Murdoch, who withdrew his support for Mr Brown in the 2010 general election.

Mr Murdoch and his fellow conservative newspaper owners have never given Labour support since.

The general election in 2010 had no winner. A coalition government was formed between the Conservative Party, led by David Cameron, and the Liberal Democrats, led by Nick Clegg.

Gordon Brown stood down as Labour leader. The contest to replace him was between the Miliband brothers, David and Ed.

David, regarded as the more capable of the two, was closely identified with Mr Blair. He never stood a chance.

Ed Miliband was elected leader by the party. He moved Labour back towards its more socialist, pacifist roots. His most notable act was to lead a parliamentary vote against joining the US in bombing Syria after its president, Bashar Al Assad, used chemical weapons against his own people.

Even though then-president Barack Obama considered the use of chemical weapons to be a red line, he decided not to use force against the Syrian leader after the UK declined to join America in military action.

In the 2015 general election, the Conservatives won a straight victory over Labour. Mr Miliband resigned and the party selected Jeremy Corbyn as leader.

Mr Corbyn returned the party the rest of the way to its pre-Blairite status quo. Anti-Americanism and pacifist socialism had been Mr Corbyn’s worldview for 50 years. A key part of that worldview was that the European Union was a tool of global capitalism.

When Mr Cameron called a referendum on Britain leaving the EU, Mr Corbyn was exactly the wrong person to use his position as party leader to convince Britons to vote Remain. The country voted for Brexit by a small majority.

In 2019, Mr Corbyn led Labour to its worst electoral defeat in 85 years. “Corbyn would not have happened without Blair’s Iraq folly,” Mr Lustig asserts.

Ed Miliband and Syria, Mr Corbyn and Brexit. How different Britain would be today without 9/11 and Mr Blair in charge, committing the country to fighting alongside America, come what may.

Today, the Conservative Party has an 80-plus-seat majority in Parliament. Labour is now led by Keir Starmer, a remarkably uncharismatic lawyer. The party still remains split over the Blair legacy.

Historical precedents say it will take at least two elections for Labour to overturn the Conservative majority. The next one is scheduled for 2024, and under the Fixed Term Parliament Act, it could be another five years before another is held after that.

The Conservatives have been in government since 2010. There is a good chance they will still be there at the end of this decade.

When Osama bin Laden gave the greenlight for the 9/11 attacks, his target was America.

He could never have thought that their success would lead to twin wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and that the Iraq war in particular would lead to the destruction of the Labour Party, turning Britain into a one-party state.