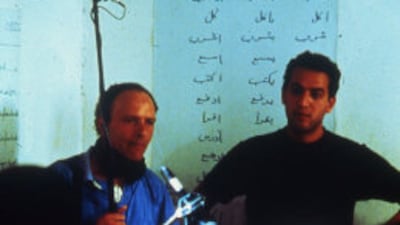

The first time that Omar Al Qattan filmed in the Palestinian territories, he was a 22-year-old on set with his mentor, the director Michel Khleifi.

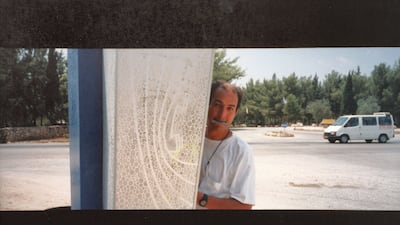

Happy weeks were spent scouting locations in the West Bank region in search of the perfect settings for the scenes depicted in the script in only his second visit to the birthplace of his parents. He soaked up the breathtaking scenery and filmed in a restored Ottoman fortress village surrounded by olive groves.

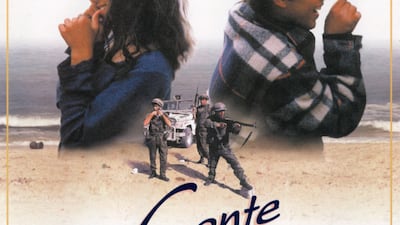

The result was 1987's Wedding in Galilee, the first studio feature film shot in Palestine, depicting life under curfew following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. It would go on to win a clutch of awards, including the prestigious International Critics Prize at Cannes, and propel Khleifi on the path to directorial eminence.

“It was wonderful,” Al Qattan recalls. “When you work in film you get to do a lot of scouting so you really know a place, especially a small place like Palestine.”

In the years since, Al Qattan has worked in and for Palestine many times, but he stresses that this has never been simply because of his own heritage. "It is a matter of a right to be able to identify with whatever you like," he tells The National. "But the issues for me are political. I think really you need to transcend these affiliations, these loyalties.

"I'm not really sure that cultural identity is actually that powerful a bond, or as powerful a bond as the sense of injustice that inhabits us to be the sons or grandsons of refugees, regardless of how successful or comfortable they turned out to be in life.

"Through this sense of outrage, anyone can identify with you, anyone can support you on that basis, whereas if you come from a sort of clannish or sectarian perspective then it becomes like a sort of closed canal.”

Al Qattan’s reference to a comfortable life is an important one. His father Abdel Mohsin went on to become a successful businessman and his son is now chairman of the foundation set up in his name.

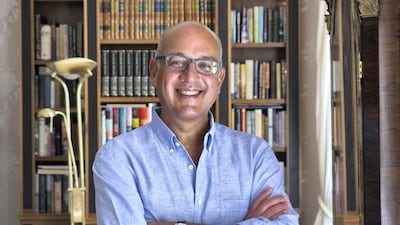

He is not one to be pigeonholed but, when asked, provides a label with a hint of embarrassment: “I guess ‘diaspora philanthropist’ is about right.”

The answer is rooted in the journey of his parents as refugees from Palestine – his father after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war and his mother, Leila, after her family was exiled during the British Mandate over her father’s refusal to salute the Union flag. They met and married in their country of refuge, Kuwait, while working as teachers. There, they had three children before moving to Lebanon for their education where their fourth child, Omar, was born.

Al Qattan points out that, in fact, he belongs to many diasporas – those of Palestine, Kuwait and Lebanon. “It might seem confusing to some that I have these multiple identities but it's not an invention of mine; it's the reality of my life,” he says. “I find that it’s incredibly enriching. I don't think it's an issue.

“It was a problem when I was younger, for sure. When I became an adolescent, it did seem sometimes like it would be so nice just to be an English boy without these complications. But now I think how impoverishing that would have been if I had sort of ignored the rest and how isolating as well.”

When the young Omar was sent to board at Millfield Preparatory School in Somerset at the outbreak of the civil war in Lebanon in 1975, he arrived in what felt like an alien culture. Unable to speak English, he ate “terrible food” and was awash with homesickness.

“I think it hardened me in a way,” Al Qattan, now 56, says over Zoom. “It made me maybe try to resist any temptations for sentimentality or nostalgia, especially after a couple of years when it was really clear that there was no going back.”

Then, though, he pined for the childhood he had left behind by the warm Mediterranean Sea and the school that more or less nestled inside a forest. It was a idyllic – until it wasn’t.

"It sort of started to dawn on me as an 11-year-old that this is not an adventure; it was very serious.”

The trauma of the rupture and the loneliness was compounded by the racism he encountered at school. Lacking the means to answer back with language, Al Qattan admits that he sometimes resorted to his fists until he developed some defence mechanisms.

He credits an “eccentric, extraordinary, generous kind of spirit” exhibited by teaching staff for helping him find his feet.

Despite failing all his secondary entrance exams except French, the teenage Omar went on to study at Westminster School, one of the country’s most prestigious. “When I asked my eventual housemaster why they'd taken me, he said: ‘Well, we've never had an Arab boy before, and we thought it would be interesting.’ Which wasn't technically true – there had been a couple of others.

“So I was in that atmosphere of, on the one hand, a lot of stereotyping and unpleasant, racist comments and, on the other hand, we were still in an era in certain sectors of British society where there was this international outlook and curiosity.”

Al Qattan found solace in books. Reading, he says, was the only way he could catch up on English. When he discovered how much he loved books, he went on to read English literature at Oxford University.

Having dabbled in theatre at school and university, Al Qattan then decided to pursue his interest across the Channel, studying film and directing at the Institut national superieur des arts du spectacle in Brussels, where he created short documentaries and dramas under the tutelage of Khleifi.

After Wedding in Galilee, Al Qattan quickly flourished in his own right. His first film, Dreams & Silence, an early exploration of political Islam, won the 1991 Joris Ivens Award and was broadcast in Europe and Australia. In 1994, under the Sindibad Films production company he co-founded, he produced Khleifi's Tale of the Three Jewels, the first feature film shot entirely in the occupied Gaza Strip. It premiered at Cannes and picked up a host of international awards.

Despite his illustrious film career, Al Qattan found himself slowly being drawn into the philanthropic arm of the “family business”. His father had made his fortune through a contracting business in Kuwait and wanted to channel his riches towards educational outreach programmes focused on the arts in Palestine.

Yasser Arafat once told Abdel Mohsin that he wished him to become the Palestinian Rothschild. “For that to happen, we need a Palestinian Ben-Gurion,” the retort came.

The famous quip by Al Qattan’s father was often repeated in public, much to the irritation of the now-late leader of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, and symbolises the family’s at times delicate footing within the political arena.

In 1993, the A.M. Qattan Foundation was born and the youngest of the Al Qattan siblings redirected his creative efforts towards empowering others. Almost three decades on, the foundation employs more than 100 people across the West Bank and Gaza.

A $24 million dark grey cube on a hillside in Ramallah was the patriarch's dying wish. Opening a year after his death in 2017, the cultural beacon that is the A.M. Qattan Foundation Cultural Centre is the first of its kind in the Occupied Territories, housing a gallery, library, theatre, artists’ residencies and public plaza.

Al Qattan also opened The Mosaic Rooms as a cultural space in 2008 in London, not far from where he now lives.

He has intermittently chaired the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit since 2012 and the Shubbak Festival of Contemporary Arab Culture in 2013 and 2015. He produced Khleifi's last film Zindeeq, which received the 2009 Muhr Award for Best Arab Feature at the Dubai Film Festival.

As well as following in his father’s footsteps in philanthropy, he also rejuvenated the waning Al-Hani Construction and Trading Company in Kuwait as a means of financing the A.M. Qattan Foundation. There, he has undertaken large-scale public projects such as the Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Cultural Centre and Kuwait National Library.

Prior to the pandemic, Al Qattan returned to Palestine often, saddened by the dramatic decline he has witnessed over the decades. “The landscape has been completely brutalised,” he laments. “It’s not just the apartheid rule but the awful settlement building, which is going on everywhere.”

But the disenchantment and cynicism among the population was the most painful to observe. “It's based on a sort of hopelessness and very dark outlook,” he says. “I find that harder to accept even than the chaos of the uprising.”

He hopes that the AM Qattan Foundation’s work can help remedy this, particularly by encouraging the involvement of youth.

Al Qattan has been actively steering the Foundation in a different direction to make it less of a family enterprise and more of an independent, public institution. But the input of the younger generation, whether his own offspring or those of others, is crucial to these plans. He says that it is far easier to shape the future with the young, who are still open to new ideas, than it is with older generations.

"If we want to build something for the long term, we have to focus on young people, especially children," Al Qattan says.

Even at arm’s length, the guiding hand of the prodigious creator is making a difference.