A veteran Iraqi economist who is advising the country's new Prime Minister, Mustafa Al Kadhimi, has revealed astounding figures on government waste in the resource-rich but impoverished nation.

Mudher Salih told of a state obsessed with generating money from its oil sector without acting to develop the country or plug holes in the budget that have been sucking liquidity out of public finances for years.

The electricity sector costs the government about $10 billion (Dh36.73bn) a year to run but generates only 7 per cent of its operating costs in revenue, Mr Salih told the official Iraqi news agency on Tuesday.

Iraq also suffers crippling power cuts and imports electricity and gas from Iran to boost production.

Official datas show its generation capacity at 16,000 megawatts, compared with the 24,000 to 30,000 megawatts needed to satisfy demand.

Mr Salih, a former central bank official, is one of the few senior independent experts in Iraq who survived purges under Saddam Hussein.

He retained a senior position in the state after the consolidation of the Shiite political ascendency in 2005, the year Iraq had its first democratic poll post-Saddam.

Mr Salih said Iraq imported $50bn worth of fuel in the past 10 years, although it is one of the top five members of Opec.

"This amount could have been used to build 10 large oil refineries," he said.

"Big structural changes are needed in the electricity and oil sector."

Mr Salih said that without "real" investment, Iraq would have no capacity to develop and progress.

Without "real" investment, Mr Salih said Iraq will have no capacity to develop and progress". He added that investment was mostly made to produce more oil and that revenues outside the sector are non-existent.

Mr Salih said the government would be taking "emergency measures and they will be very difficult, in addition to a long-term reform process to activate the private sector".

His comments echoed a warning by the World Bank in a recent report about Iraq "facing a combination of acute shocks, which the country is ill-prepared to manage".

The report, from spring this year, highlighted challenges including the collapse in oil prices, the coronavirus, pandemic and "growing discontent over poor service delivery, rising corruption, and lack of jobs."

The World Bank predicted a debt trap that would "create pressures on the exchange rate and inflation".

It assumes that if oil prices stabilised in the low $30s a barrel, Iraq would still need to raise $67bn in financing, equal to 39 per cent of gross domestic product, to cover spending.

"Implementing reforms in Iraq has become even more crucial for the sustainability of growth and job creation," the report said.

Mr Al Kadhimi has signalled his intent to fix the economy by appointing his confidant Ali Allawi, a former investment banker, as Finance Minister.

He said he found state coffers were "nearly empty" when Parliament confirmed him as premier on May 5.

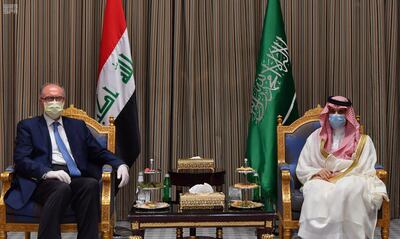

Mr Allawi's first trip abroad as an official over the weekend was to Saudi Arabia, the default destination for most Arab nations in economic trouble.

In March this year, Mr Allawi made a presentation at a closed-door meeting in Berlin in which he charted a historical analysis of corruption in Iraq.

A copy of the presentation, entitled The Political Economy of Institutional Decay and Official Corruption: The Case of Iraq, was seen by The National.

Mr Allawi said that until the 1980s, "Iraq was not perceived as a corrupt country".

He traced the start of the malaise to the 1970s.

He said fear of the one-party Baath state in that decade and "ideological fervour" replaced "religio-ethical norms and conventions as the main enforcement tool to prevent the occurrence of widespread corruption".

Mr Allawi said the First Gulf War in 1990-1991 ushered in "catastrophic economic, social, and administrative collapse".

It was superseded by the era after the US-led invasion in which he said corruption "had risen markedly, and institutional decay was everywhere".

Mr Allawi said he had come across estimates of individual Iraqi assets outside the country of between $100bn and $300bn.

"The best estimates are approximately $125bn to $150bn," he said. "The large majority of these assets are illegitimately acquired."