After more than a decade of leadership turmoil, outsiders would be forgiven for switching off from the latest election in Australia.

After all, in a country with a parody Twitter account (@WhoIsPM) that gives twice-hourly updates on who is currently in charge of the nation, it can feel futile to commit to learning very much about the current prime minister.

And by the polls, which put the opposition Labor Party marginally ahead on Monday, it is likely that conservative Prime Minister Scott Morrison will lose his job after just nine months.

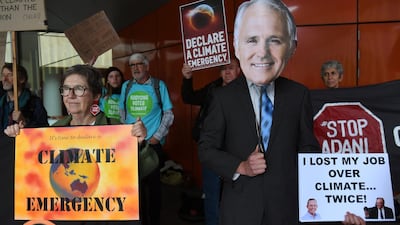

But as Australians vote at booths housed in primary schools around the nation on Saturday, May 18, there is one issue on the agenda that should make the world sit up and pay attention: climate change.

As one of the world’s top per-capita greenhouse gas emitters, and at the frontline of climate change devastation – from increasing regularity of extreme weather events and heatwaves to mass coral bleaching at the Great Barrier Reef –the environment is firmly on the agenda.

In fact, a Lowy Institute poll released earlier this month found that climate change had emerged as the No 1 concern for Australians, with 64 per cent of adults considering it a “critical threat”.

Coming amid global environment protests, Australia’s election could prove to confirm the growing evidence that climate change is overtaking other concerns, such as migration and terrorism, as the most important issue among Western voters.

Who is Scott Morrison and what are the Coalition's key policies?

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison launched the official election campaign for the Liberal-National Coalition on Sunday, promising to focus on economic management and support the “decent, simple and honest” aspirations of Australians.

He has promised to cut income taxes and to launch a first home buyer scheme, which would allow borrowers to purchase their first home with a low five per cent deposit.

But Mr Morrison has been broadly criticised for a campaign that has been light on policies and focused on criticising the opposition, despite his own party’s obvious disarray.

The conservative Liberal Party has been rocked by division in recent times, having had three different leaders in four years – with Mr Morrison coming to power by unseating former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull during yet another challenge in August 2018.

Neither of Mr Morrison’s two immediate predecessors as prime minister, Mr Turnbull and Tony Abbott, were present at the campaign launch on Sunday. Former prime minister John Howard, who led Australia from 1996 to 2007, did not show up either.

_____________

Recent Australian Prime Ministers:

_____________

Much of the rupture has been put down to an internal culture war over climate change, which has dogged the party since Mr Howard’s refusal to sign the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. The right-wing of the party is heavily influenced by self-confessed climate deniers, including another former prime minister Tony Abbott.

The Coalition has promised to cut emissions to 26 per cent less than they were in 2005 by 2030. But this is far less than what advisers say Australia needs to do in order to meet its Paris obligations.

There has also been criticism of the methods the Coalition is proposing to reach its targets, including using Kyoto carry-over credits, which are effectively bonus points accrued from Australia beating its 2020 carbon target, rather than an actual reduction in CO2.

Who is Bill Shorten and what are Labor's key policies?

Relative to the Coalition, Australia’s Labor party has had a long period of stability, with Bill Shorten now holding the position of Opposition Leader for six years.

This can be at least partly attributed to the leadership selection rules that were brought in by Kevin Rudd during his second run as prime minister, requiring that 75 per cent of the party room to agree before changing an elected leader.

While lacking in the fiery charisma of past Labor leaders, Mr Shorten does appear to have worked hard to repair much of the damage inflicted by the repeated leadership spills of the Rudd-Gillard era by prioritising teamwork and consultation.

Labor’s key policies focus on health, education and cost of living. Its housing affordability policy centres on stimulating construction of new affordable homes through reforms to negative gearing and capital gains taxes, rather than granting government loans to buyers as the Coalition is promising.

On climate change Labor is targeting a 45 per cent emissions cut by 2030. The party promises to do this through several mechanisms, including the national energy guarantee – a policy originally devised by the Coalition and later abandoned which requires energy retailers to reduce emissions.

The party also plans to make 50 per cent of new cars electric by 2030.

But Labor has been criticised for plans to spend A$1.5bn (Dh 3.8bn) boosting natural gas supplies in Queensland and the Northern Territory, as well as its ambiguity over the highly contentious proposed Adani coal mine.

What are the latest polls predicting?

Labor retains a narrow lead according to Newspoll, which put the opposition ahead of the ruling Coalition, 51 per cent to 49 per cent on Monday.

The polls are unchanged over the past two weeks on a two-party preferred basis. Based on the poll, Labor would have 77 seats in Australia’s lower house, just one seat above the 76 required to form a government. The Coalition would have 68 seats, with six going to other parties.

Currently, Labor holds 69, the coalition 73 and other parties 8.

The Newspoll also showed voters' net approval of Mr Shorten climbed eight points to his highest since March 2015, although his rating still trails Morrison's, by 10 points.

The election contest is expected to come down to a number of tightly fought seats in the eastern states of Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, many of which feature independent candidates pushing for strong action on climate change.

Why are Indigenous people taking Australia to the UN?

Lawyers for eight residents of the Torres Straight Islands, a group of more than 270 low-lying islands between Australia and Papua New Guinea, said on Monday that they would file an unprecedented complaint against Australia to the UN for falling short of its Paris climate accord pledges.

Australia is among the 185 countries to ratify the Paris Agreement on global warming, pledging to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 26 to 28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

But the country last year stripped requirements for cutting emissions from its centrepiece energy policy and has since been warned by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that it needs to cut emissions more sharply to meet its targets.

Lawyers said the complaint could take up to three years to be ruled on at the UN. They added that it would also be the first legal action worldwide brought by inhabitants of low-lying islands against a nation state.

The complaint argues that Australia lacks adequate policies to cut its emissions, contributing to rising sea levels that are already threatening homes and damaging burial grounds and sacred cultural sites on the islands.

The Australian government has also failed to fund adequate coastal defences like sea walls, the complaint said.

Those behind the action are worried their islands could disappear beneath the ocean in their lifetimes, curtailing their ability to practice their law and culture.

"We're currently seeing the effects of climate change on our islands daily, with rising seas, tidal surges, coastal erosion and inundation of our communities," Kabay Tamu, one of the plaintiffs and a sixth-generation Warraber man, told Reuters.

"If climate change means we're forced to move away and become climate refugees in our own country, I fear this will be colonisation all over again."

While Australia would not be forced to comply with the UN panel's ruling, Sophie Marjanac, one of nine lawyers involved in the case, told Reuters that any decision in favour of the islanders would be a moral and political victory for them.

A spokesman for Australian Environment Minister Melissa Price said the government was committed to addressing climate change by meeting its international targets, investing in renewable energy technology, and protecting the environment.

Why do so many people vote in Australia and what is a ‘democracy sausage’?

Australia has boasted voter turnout figures of above 90 per cent in its recent federal elections.

This is largely because voting is compulsory in Australia, with failure to vote at a federal election without a valid and sufficient reason attracting a fine of A$20 (Dh51).

However, there has been in an increase in recent years of people spoiling ballots or casting “donkey votes”, where an elector numbers the preferential ballot paper from top to bottom regardless of preference.

Another quirky feature of Australian voting is the barbecued sausage wrapped in a slice of bread that is served up at polling booths around the country.

The charity sausage sizzle has long been a part of voting in Australia, but the term “democracy sausage” first entered popular lexicon in 2012 and has since become known worldwide.

The humble sausage (usually made with beef and /or lamb) has not been immune to change, with many food stalls now offering vegan, gluten free and hipster-friendly toppings including avocado and pulled meats.

However, the most heated debate has not been about the gentrification of the sausage, but whether the fried onion should be placed on top or below it (on top, obviously).

Twitter hashtags #Auspol #Ausvotes and #democracysausage even include a sausage emoji, while a website has been created to map the locations of election day barbecues – and polling booths – across the country.

* With additional reporting by Reuters