Adeeb Sami was lying on the ground in Al Noor Mosque, a bullet lodged in his spine and another in his shoulder, as his son Ali, 23, frantically pressed at his wounds to stop the bleeding.

He remembers thinking that this was probably the end. So he knew what to say.

“I said to him, ‘You have to look after your mum and your sisters’, and Ali said, ‘Dad, why are you talking like that?’

“I said, ‘It’s like in the movies, you have to say that’.”

That dark humour runs throughout Mr Sami’s recollections of that day on March 15, when a terrorist entered two Christchurch mosques and carried out New Zealand’s worst mass shooting, killing 51 people.

What else can he do but laugh about it all now, he says. After all, he spent much of his life in Iraq but “came to New Zealand to get shot”.

But the humour is laced with sadness. The sounds of his friends taking their last breaths around him still come to him at night.

It is the last night of Ramadan, and the Adeeb family are have gathered at their cliffside home in Christchurch for iftar.

Mr Sami’s wife Sana Mullayounus and his daughter Hamsa, Ali's twin, are cooking mountains of food in the kitchen, while he breaks his fast with dates from the UAE. Despite his wounds, he has fasted all month.

The call to prayer sounds through the house a little after 5pm as the family gather to pray. The only way to tell that Mr Sami was inflicted with a near-fatal injury three months ago is that he is rising and sitting on a stool rather than kneeling.

Mr Sami does not know how he is walking around again so soon, and says even his doctors are astounded.

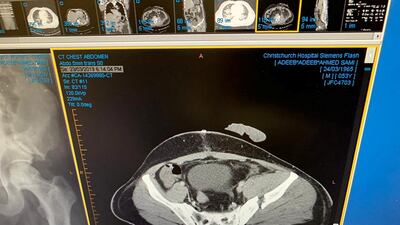

He shows off an X-ray proudly, pointing out an almost polka-dot array of shrapnel still lodged in his side and a cavernous fracture in his pelvis.

Mr Sami flies back to the UAE on Friday to resume his job as a director at Aecom, and he will carry a clearance letter for airport security to prove that the metal setting off the detectors is inside him, rather than on him.

“They called me ‘the penguin’ for a long time because of the way I was walking,” he says from the head of the table.

Laughs erupt from his older son Abdullah, 29, and Hamsa, while his wife shakes her head with a wry smile.

“When I woke up from the coma someone asked me how I was feeling and I said, ‘Like I’ve just been shot'.”

Mr Sami was supposed to fly to Christchurch with his wife on April 1.

“Whenever I got to bed somebody was whispering to me, ‘You have to go to Christchurch on March 14’,” he says. “So I changed all the flights. It cost me a lot of money.”

The morning of the attacks was Hamsa and Ali’s 23rd birthday. Mr Sami had not yet told his Christchurch friends that he was back in the city.

He wanted to do so by posting a picture on Facebook of the sweeping seaside views from his coastal home, and one of his car’s personalised "Adeeb" licence plates, with the caption "Home sweet home". He decided he would do that later, after Friday prayer.

Instead, he went off to renew his passport with Hamsa. A beaming selfie of the two of them at a cafe was taken at 12.51pm, less than an hour before the attacks began.

Mr Sami then left his daughter and went to Al Noor. He did not know Ali was there, or that Abdullah was on his way, too.

“The imam did the speech in Arabic and he had just started the speech in English. I remember, he had just said: ‘My dear brother and sisters’. And then we heard shooting.

“I thought it was a joke or someone making fireworks.”

Mr Sami was hit by a bullet in the side almost immediately. He was sitting beside his friend, Abdelfattah Qasem.

“I felt I got the bullet and I directly lay down. In that moment, Fattah said, ‘What’s going on Adeeb?’ and I said there’s a bullet in my back.

“He said, ‘Don’t worry, I will save you.' And then the shooter came back and shot him.”

Mr Qasem died in the attack.

As the shooter returned to his car to reload, Mr Sami saw Ali in the back room, dialling 111.

He dragged himself to his son and told him to put his phone down and lie on the ground, throwing himself on top of him.

“The guy returned back and started shooting again. This time he used a different weapon.

"Whoever he sees alive he’s shooting again. I remember some guys, they started loudly praying in Arabic, and he came and shot them one by one.

“Then I got the second bullet in my shoulder, which came exactly by Ali’s face. He had a big red mark from it. I could feel him shaking beneath me.

“The whole eight minutes, I thought it’s the end. The whole time I was thinking about Ali, I wanted Ali to be safe.

"I couldn’t describe my feelings when I knew he had survived, I’ve never been so happy.”

Only three people rose after the shooter left Al Noor, and Ali was one of them. He took off Mr Sami’s trousers and used them to press on his wounds.

He remembers someone near by asking him for help, and him saying he needed to help his father first. He still does not know who that person was.

It was then that Mr Sami told him to look after his family, joking that it was what people say in the movies.

“I was hearing my friends around me making the gurgling sound. Until now I can hear it in the night. Fattah was sitting so close to me. He was the first guy I met when I came to this country.

“I sat down with those guys before the shooting and after, I saw them lying down like that.”

Across town, Hamsa and Sana had just walked into a supermarket.

“One of my friends called me and said, ‘Did you hear anything from Adeeb?’ I said, ‘What, he’s at the mosque, he’s praying'," Sana says. "I didn’t know Ali was at the mosque. That’s when Hamsa said Ali had started going.

“I was driving like a crazy person. Hamsa got out and ran away through Hagley Park to go to the mosque.

"One lady came from Hagley and said, 'He’s still shooting people'. When I knew that my husband and my son was there I fell down to the street.”

The family converged on the hospital, with hundreds of other distraught families looking for loved ones.

“We were asking about the name, Adeeb Sami, and they said we don’t have the names, we gave them numbers.”

Mr Sami’s injuries were so severe that he was immediately placed in an induced coma.

His friends were astonished to see him there, not knowing he was in the country. Mr Sami blames that failed Facebook post.

He was in a coma for three days, undergoing three major, life-saving operations.

But he still remembers the first thing he asked for when he woke up.

“I couldn’t talk… they gave me the board to write something. I wrote ‘Federer’.”

Mr Sami dissolves into fits of laughter as he recalls his first lucid moments after being shot twice, asking for the outcome of the Indian Wells Masters. For the record, Federer lost in the final.

“You can see what’s important to him,” Sana says.

Mr Sami spent 19 days in hospital, before being discharged to recover at home.

Photos from the following months show him in a hospital bed flanked by his family, and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, or with Prince William, or with Ms Ardern again during another visit to the city.

They also show his wizening body, losing 14 kilograms in the months since. That photo from the cafe with Hamsa, taken just before the shootings, looks almost like a different person.

“Prince William said it would take a year or so to recover and I said, ‘No I’m from Iraq’. And he said, ‘You’re well versed in it then’,” Mr Sami says.

The day he arrived home, he posted that "home sweet home" Facebook post. He had promised Christchurch mayor Lianne Dalziel he would.

Mr Sami has nothing but praise for the response of emergency services, and the government, after the attacks.

He recalls being near by when a car bomb went off in Baghdad in 2006 and the emergency response taking much longer.

He does not blame the shooter, either.

“You have to blame the leaders who fuelled that hate speech. But Jacinda changed it to a speech of love. She protected the Muslim community.

“He shot us again and again. Until now I ask myself, if you’re a human being and you hit a dog while driving, could you turn around and hit him again?

"Why this amount of hate? He shot 80 people in eight minutes. Each minute he killed or injured eight people.”

Recovery has been long and difficult. Mr Sami now has a 35-centimetre scar running down his torso, and a colostomy bag. He will have to fly back in September to have that removed.

Christchurch is still one of his homes and he still loves it. And perhaps some good can come from the attacks, he muses.

“We’ve never had problems, but for them I’m something different,” Sana says.

“I’m wearing my scarf even when they’re wearing shorts and skirts. I’m still full of clothes. People are talking more to me now.”

Given that Ali and only two others saw clearly what happened in the mosque that day, he has had to face questions from a lot of family members who want to know what happened in their loved ones’ final moments.

“I am lucky. But in a way, I’m like ‘Why?’ and now I need to find out what’s my reason,” he says. “Why did God save us? We have to make something good out of life.”

Father and son agree that life has changed. Small moments have taken on new significance and they have become more thoughtful, more reflective.

“God sent me on the 14th,” Mr Sami says, “and he saved me also when he stopped my bleeding.”

It is not exactly a higher calling, but something of a wider purpose, he says.

But you will not ever stop him from posting on Facebook about Roger Federer.