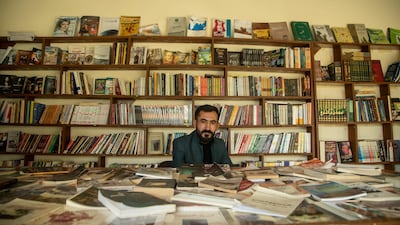

Books were Kamiran Khalaf's sole consolation after ISIS stormed his homeland in Sinjar. Now he wants them to help heal the wounds of his city and society after the militant group's genocide against the Yazidi minority.

Opening a bookshop in the northern Iraqi city, parts of which are still in ruins six and a half years after the massacre, seems a brave venture, but for Mr Khalaf, 25, it is a remedy for his tortured homeland.

"It's not just a bookstore, it's an idea to salvage Sinjar from the killings, conflicts and strife", he tells The National at the recently opened venue, set in a small park in the bustling city centre.

To reach that goal, Mr Khalaf hopes to "boost culture to weed out the sectarian ideas and strife among the segments [of the city's diversified society] and plant humanity, love and peace among them again".

As well as Yazidis, Sinjar and surrounding areas were home to other religious and ethnic groups, including Sunnis, Shiites and Christians.

For centuries, the Yazidis – who follow an ancient monotheistic religion, but are falsely seen by some as devil-worshippers – lived in the mountains in north-west Iraq where their ancestral villages, temples and shrines are located.

They cite discrimination and second-class treatment by governments and society, a feeling that turned them into a closed community.

In August 2014, ISIS fanatics captured Sinjar and surrounding villages, taking thousands of Yazidis captive and slaughtering others. Thousands of young women were forced into sexual slavery by the militants while mass graves containing the bodies of thousands killed are still being uncovered.

Others fled in time, escaping to nearby Mount Sinjar, where many were flown to safety by the US-backed Iraqi forces. Some, like Mr Khalaf's family, travelled to Syria on foot, including his ailing mother, who made the difficult journey barefoot.

“They stayed for 13 days in the mountain in fear and horror without food and drink and under tragic circumstances,” Mr Khalaf recalls bitterly.

“Some people were dying in front of their eyes of hunger and thirst. Some had to make hard choices to take one of the parents because they couldn’t carry both. It was a real disaster.”

He was working in another part of Kurdistan at the time, but weeks later the family reunited in one of the displacement camps in northern Iraq, where despair crept over him.

“We lived in hell inside the camp. Whenever the pain increased, I read, read and read until reading became like eating and drinking to me,” he says.

To help others escape the new reality, he turned a small tent into a free lending library with about 600 books gathered from his own collection and donations covering a range of literary genres. The idea was welcomed by camp inhabitants, particularly young people looking for ways to kill time and escape the monotony of camp life.

In November 2015, a US-backed patchwork of armed forces – made up of Baghdad-run troops, Kurdish fighters, Yazidi militias and Turkish Kurdistan Workers’ Party rebels, known as the PKK – took back Sinjar and surrounding villages.

“The city was scary,” Mr Khalaf says, describing a visit to Sinjar a few weeks after the liberation.

“No one was in the streets except the fighters and stray dogs ... with three quarters of the houses booby-trapped [by ISIS], others demolished and charred cars.”

Last October, his hard work paid off and he realised his dream of opening a bookshop in Sinjar, helped by a grant from Germany’s Goethe Institute, which covered half of the total cost of $7,000.

Books started to pour in from activists and publication houses in Iraq.

Now, his Urshina bookshop, which means the Land of Peace in the old Syriac language, offers about 5,000 titles, including novels, poetry, politics, economy, history, philosophy and celebrity biographies.

The prices are affordable, ranging from $0.70 for children’s stories to $35 for a set of encyclopedia. He also lends them at a nominal fee to encourage reading.

Books are neatly organised on wooden shelves or spread on a table in the middle of the small shop, while others are suspended from the ceiling.

The selection is varied.

There are titles by Yazidi authors who tell the story of the horrific suffering their people have endured. Among them is The Last Girl by Nobel Peace Prize-winner Nadia Murad about her enslavement under ISIS.

Others are novels by Iraqi writers chronicling Iraq under Saddam Hussein and the events that followed the 2003 US-led invasion, including the award-winning author Ahmed Saadawi's Frankenstein in Baghdad.

Also on display are books translated into Arabic, including Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and The Sea and Plato's The Republic.

“These books are the only rescuers for Sinjar,” Mr Khalaf says.

He believes that the city needs a cultural and intellectual rebuilding “to be linked to Baghdad and other areas through culture and to gain its weight and value among Iraqi society”.

Every Friday he invites residents – mainly young people – to the park to discuss books and attend readings, which he plans to expand to workshops and other cultural events that reach out to the wider community beyond Sinjar.

“We had enough wars, we want to live in peace,” he says.

After enduring 74 assaults since the late 16th century, Yazidis need more than just security and services, he says.

“We want peace, humanity and respect as a segment who lives in Sinjar. We don’t want to be like Jews and Christians who have fled Iraq.”