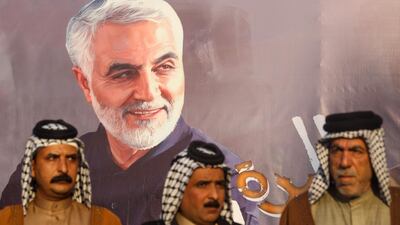

A year after the US drone attack on Qassem Suleimani, the assassination of the commander of Iran's elite Quds Force and architect of Tehran’s proxy wars in the Middle East still reverberates.

His sudden death was not only a game changer in the US-Iran stand-off in the region, but also left a huge void in the Iraqi arena and opened a Pandora’s box of unrest in the country.

In a documentary to commemorate the first anniversary of Suleimani’s death, former Iraqi prime minister Nouri Al Maliki acknowledged that “the situation in Iraq has been hugely impacted”.

In the 12 months since Suleimani was assassinated alongside top Iraqi militia leader Abu Mahdi Al Muhandis, the security situation has disintegrated as Iran-backed militias assert their authority on streets where Iraq’s government, weakened by a year of pro-reform protests, a severe Covid-19 outbreak and an economy that is teetering on the edge of collapse, has little control.

Shortly after midnight on January 3, 2020, Sham Wings Airlines flight 501 from Syria landed at Baghdad International Airport with Suleimani among its 156 passengers.

Al Muhandis, deputy head of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Forces, which is primarily made up of Iran-backed militias, waited near the passenger stairs to receive the important visitor, unaware of three US drones circling overhead.

As the two men and their seven aides drove away from the airport, two missiles were fired from the drones. One hit the entourage vehicle, while the other missed its target. A third missile followed, hitting the speeding car carrying the two leaders. Both were killed.

Hours later, US President Donald Trump – who ordered the operation – claimed that the killing of the man he referred to as the "number one terrorist anywhere in the world" had saved the lives of American personnel that Suleimani intended to kill in planned attacks in Iraq.

But security experts say the assassination heightened tensions and exacerbated the risks faced by US personnel on the ground there.

From a political and security perspective, the situation today is "more unpredictable, more dangerous" than it was when Suleimani and Al Muhandis were alive, Sajad Jiyad, an Iraq-focused analyst and fellow at The Century Foundation, told The National.

“If the Americans thought that they would make things better or safer for them, or his loss would mean that Iran becomes weaker, the events this year show that’s not true,” he said.

A few days after the assassination, Iran retaliated by firing nearly two dozen ballistic missiles at two Iraqi military bases where US troops were stationed.

Hours after the attack, the Pentagon reported 11 US soldiers wounded, but a month later the number increased to more than 100 soldiers who sustained traumatic injury in the attack.

Meanwhile, influential Iran-allied Shiite militias grew more defiant after Suleimani's death, launching further rocket and bomb attacks on US assets in the country.

Critics of the Iran-allied militias in the PMF, or the Hashed – the umbrella term used to describe the militias – were targeted in a series of assassinations as the security environment became increasingly lawless in Iraq.

Suleimani was the focal point for much of Iran’s policy in Iraq. He not only played a broker role in forming Iraq’s successive Shiite-led governments, but was also integral in forming, training and funding the Shiite militias that gained influence after the 2003 invasion that overthrew former dictator Saddam Hussein.

When ISIS overran the country in 2014, he orchestrated the fight against the militants through the government-sanctioned PMF.

His popularity was reinforced by images from the front lines of him instructing field leaders in fluent Arabic and sharing food and tea with the fighters.

In the absence of Suleimani and Al Muhandis, divisions emerged among different factions inside the PMF.

“Al Muhandis was a recognised leader of the PMF, all the groups recognised his leadership, they listened to him,” Mr Jiyad said.

With his death, the groups are becoming “more disunited and that will lead to more competition, more unpredictability and there is going to be less and less control over the PMF”, he said.

That division became clear during the pro-reform protests in Iraq last year, when Iran-backed militias were accused of targeting protesters and activists in violent crackdowns.

Since taking office in May, US-backed Prime Minister Mustafa Al Kadhimi struggled to control the militias.

In one recent incident, security forces arrested nearly a dozen militiamen accused of plotting a rocket attack against the US embassy, but they were released days later under pressure from militia leaders.

The assassination last January coupled with the protests "made Iran-backed militias stick together as they feel they are facing an existential threat", said Hamdi Malik, associate fellow at the Washington Institute think tank.

"But they are experiencing growing division," because of the absence of Al Muhandis, he said.

Iraq-US relations also suffered in the aftermath of the assassination, with pro-Iranian politicians in parliament pressing for the expulsion of US troops from Iraq.

The regular attacks against the US embassy in Baghdad and logistics convoys for the US-led International Coalition by previously unknown Shiite militias increased tension on the ground ahead of the anniversary, and President Trump vowed to retaliate if any soldier is killed by such attacks.

Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei warned on Thursday that “revenge ... is certain and will be exacted at the right time”, state news agencies reported, after the country announced that it is ready to charge 48 individuals who authorities believe to be behind the assassination.

As the anniversary approaches, the atmosphere in Iraq is tense and Iraqis are worried that a new cycle of violence could erupt if US assets in Iraq are attacked once more.