Just how far Col Muammar Qaddafi is disliked and isolated in the region and beyond was highlighted when, with characteristic effrontery, he appealed for Arab and Muslim solidarity against foreign air strikes on Libya.

His March 20 call to help confront “this aggression” did not resonate. Days later, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates contributed warplanes to enforce the western-led no-fly zone.

Unlike other authoritarian figures in the Middle East, Libya’s “Brotherly Leader” has no friends, allies or proxies.

Saudi Arabia accused him of plotting to assassinate King Abdullah, then crown prince, in 2004, and Col Qaddafi has alienated and infuriated fellow Arab leaders over the decades.

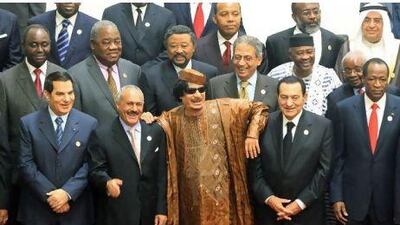

He regularly berated them in personal terms after huffily turning his back on the Arab world to seek closer ties with Africa, where he has titled himself “King of Kings of Africa”. There, with the exception of a handful of countries including Zimbabwe, he is regarded with similar disdain.

“No one likes Qaddafi. He’s quite possibly the most unpopular Arab leader. His regime is unique in not having any positive distinguishing characteristics of any kind,” said Shadi Hamid, director of research at the Brookings Doha Center in Qatar. Nor does it have any “recognisable ideology”, he added in a telephone interview.

Col Qaddafi is equally unpopular on the “Arab street” where sympathies, fanned by the eager reporting of Arab satellite channels, are strongly behind the Libyan rebels, despite deep suspicion of western motives.

"Never in modern history has an Arab ruler been almost universally reviled by both Arab governments and the Arab public," Shibley Telhami, a Middle East expert at the University of Maryland in the US, wrote last week in Politico, a Washington-based multimedia journal.

“Even among those who oppose the West, such as Hassan Nasrallah of Hizbollah, hatred of Qaddafi trumps anger with the West.”

Lebanon’s Shiites hold him responsible for the disappearance of their charismatic cleric, Imam Mousa al Sadr, when he visited Libya in 1978.

Palestinians, meanwhile, remember Col Qaddafi’s expulsion of thousands of Palestinian workers from Libya in 1995. It was his theatrical way of demonstrating that the Oslo agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organisation two years earlier had failed to solve the Palestinian problem.

For Cairo, Col Qaddafi has long been a temperamentally unstable neighbour. Relations have oscillated since Egypt won a decisive border war against his forces in 1977. They nosedived in late February when Col Qaddafi’s regime accused Cairo of helping to foment the rebellion in Libya.

Ordinary Arabs, who are striving for dignity as well as freedom, regard Col Qaddafi as a despot. And they are aware of how his theatrics play in the West.

For decades he has strutted the stage as a self-styled philosopher, delivering quixotic speeches full of sound and fury, accompanied by extras including gun-toting female bodyguards and curvy Ukrainian nurses.

Gerald Butt, a Cyprus-based author of several books on the region, says Arabs know Col Qaddafi “has done the Arab image no good”.

It was not always this way. In the early 1970s, Col Qaddafi cut a dashing figure as a swashbuckling young revolutionary. Western media seeking interviews stood a better chance if they sent a woman reporter. Most relished the assignment.

But like many rock stars, Col Qaddafi refused to quit in his prime. “The contrast in his looks and appeal between now and the early 1970s could not be greater,” Mr Butt said.

Cosmetic surgery and a hair transplant in the mid-1990s served only to make the Libyan leader look raddled and bizarre.

His ill-advised grooming, of course, pales in comparison to his other actions: years of hardline rule and, most recently, his decision to wage war on his people when they pressed for change.

Mr Telhami, who takes opinion polls in Arab countries, wrote: “Popular blogs and commentaries reveal that, despite ambivalence, Arabs who oppose the [western-led no-fly zone] intervention remain a minority.”

There have been no demonstrations in the Arab world to protest against the allied strikes. Even so, there has been agonising in the opinion pages of many Arab newspapers about that intervention.

“Much as Qaddafi is despised, it’s painful for Arabs to see western warplanes hitting an Arab state again,” Mr Butt said in an interview. “Many believe it’s a plot to seize control of an oil-producing country, not to protect Libyan civilians.”

Arab governments knew, however, that there was little risk of a popular backlash when, in an unprecedented decision, the Arab League invited the UN Security Council to intervene in a member state.

Their imprimatur paved the way for France and Britain to secure vital international legitimacy for the no-fly zone. The US had taken a back seat until then.

In stark contrast, with the exception of Kuwait, there was unanimous Arab opposition when the US, without a similar UN mandate, led the invasion of Iraq in 2003 that toppled Saddam Hussein.

“Saddam was viewed differently in the region,” Mr Butt said. “No one approved of his violent excesses against his own people, but he was somehow respected as a strongman who consistently stood up to the West.”

Support for action against him has come from the most unlikely figures, including Sheikh Yusuf al Qaradawi, an influential, Egyptian-born cleric and strong critic of US policy, who appears regularly on Al Jazeera.

He scoffed at Col Qaddafi’s portrayal of the air strikes as a “crusade” and insisted that the Libyan leader was no model of what a good Muslim leader should be. The cleric also issued a fatwa authorising Libyan security forces to assassinate Col Qaddafi.

There was stinging condemnation, too, from prominent Saudi clerics who were approached by sons of Col Qaddafi in late February, hoping to secure religious rulings against the revolt in Libya.

One cleric, Ayedh al-Garni, replied: “You are killing the Libyan people ... You are killing old people and children. Fear God.”

It is hard now to imagine that Col Qaddafi once dreamed of becoming a champion of the Arab world in the mould of his great idol, the Egyptian revolutionary leader Gamal Abdel Nasser.

He embraced Nasser’s pan-Arabism early in his rule and tried, without success, to merge Libya, Egypt and Syria into a federation. A similar attempt to join Libya and Tunisia together ended in acrimony.

Rebuffed in his efforts to unite the Arab world, Col Qaddafi turned his ambitions towards Africa in the 1990s. He adapted his wardrobe accordingly, sporting colourful clothes emblazoned with emblems of the African continent.

He lobbied in recent years for an “alternative USA” – a United States of Africa. But his grandiose schemes met with as little enthusiasm in Africa as they did before in the Arab world, which is now anxiously waiting for him to quit the stage before it is drenched in more blood.