“In the first six months of last year, we had six cases of lung cancer,” said Ali Soufan, a pulmonary specialist at Alaa Eddine hospital. “In the past six months, we had 60.”

Dr Soufan blames the increase on the widespread burning of rubbish, an ad hoc solution to Lebanon's latest waste-disposal crisis which began more than two years ago when the country's main landfill closed, leaving refuse to pile up on streets.

The rubbish crisis has become a potent example of the Lebanese state's dysfunction. Former prime minister Tammam Salam called Lebanon a “failed state” in May last year after members of parliament failed to elect a government despite meeting more than three dozen times. Lebanon spent nearly two years without a government until one was formed under the premiership of Saad Hariri late last year.

Stopgap solutions have included the open burning of rubbish at temporary dumping sites across the country. The resulting air pollution at first affected mostly poorer areas of the country but has become so widespread that Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a report this month entitled “As if you are inhaling your own death: the health risks of burning garbage in Lebanon”.

The environment minister responded by insisting things were fine.

“We should not alarm people with a problem that does not exist,” Tarek Khatib told Lebanese channel OTV.

But in the area where Dr Soufan practises, south of the coastal city of Saida, smoke from burning rubbish regularly engulfs nearby neighbourhoods. On a recent evening, it spilled over the country’s main highway as the sun set, diffusing the light and obscuring what was otherwise a clear blue Mediterranean sky.

Dr Soufan, who said the pollution was affecting increasingly younger patients, sighed when asked if he had raised the problem with the local municipality.

“They say they are not the ones doing it,” he said. “And there are some groups that don’t want it to stop.”

Mr Hariri's government had promised to tackle the rubbish problem but faced its own crisis in November when the prime minister issued a surprise resignation that threatened to send the country back into political paralysis and stoked fears of an economic collapse. The crisis was resolved — at least for now — when Mr Hariri withdrew his resignation, but not without diplomatic intervention by France, the country’s former colonial ruler.

Mr Hariri said he had tendered his resignation to send a “positive shock” to Hizbollah, the Lebanese party and militia that has grown in the past five years from a non-state actor confined to Lebanon into an army with influence across the region.

But for all its problems, does Lebanon indeed qualify as a “failed state?”

The country certainly fits many of the criteria: non-state actors wield considerable power, corruption is widespread, external intervention by other states is a norm. Daily electricity cuts are a fact of life in even the most affluent parts of the country, and the only truly safe drinking water comes from a bottle.

_______________

Read more:

Few signs of economic progress during Lebanon's 'year of the ostrich'

Lebanon must present a more appealing face to foreign tourists

_______________

“For me, failed state is if you’re talking about Beirut in the 1980s, or Somalia — that’s not what Lebanon is,” said Nadim Houry, director of HRW’s Terrorism and Counter Terrorism Programme. “I would say it’s a proto-state. During and since the end of the civil war, it’s a state that has outsourced or abandoned many functions.”

The Washington-based Fund for Peace publishes an annual Fragile States Index that this year ranked Lebanon the 43rd most fragile state out of 178 countries, a slight improvement from last year. From 2005 to 2013, the list was called the “Failed States Index” but the fund abandoned the term in 2014 as “loaded” and adopted “fragile” instead.

If he could fix only one problem, Fady Jreissati, chief executive of Lebanon's Sakr Real Estate Group, said it would be corruption.

“It is affecting the economy, the trust in the government, and the international donors for Lebanon. If you need funds, the funders will question every single dollar. It affects the trust of the locals and the diaspora,” he said.

Mr Jreissati is also the president of Lebanese National Energy, an NGO that seeks to “boost the Lebanese economy … and stop brain drain”. Lebanon’s economy is reliant on remittances from abroad, another mark of a fragile state. Mr Jreissati hopes the group can create an environment that encourages young Lebanese to stay in Lebanon rather than seek their fortunes abroad.

He hoped some of the government’s recent accomplishments would increase investor confidence.

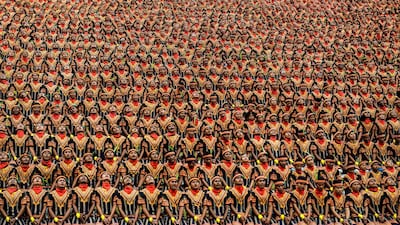

Earlier this year, the Lebanese army, along with Hizbollah, retook parts of northern Lebanon that had been controlled since 2014 by armed groups connected to Al Qaeda and ISIL.

As far as failed states, Lebanon’s solutions to problems are sometimes a paradox: while it was positive the state had regained control of territory controlled by a non-state actor, it required the support of another non-state actor to do so.

Mr Jreissati said the instability in Lebanon predated the creation of the modern Lebanese state and its often-hostile neighbours, and that the economy would always rise and fall as a result. The solution, he said, was to continue building up the state and its economy.

“People always ask, ‘Is it the right time in Lebanon?’” Mr Jreissati said. “My answer is that it is never the right time. If you’re asking that question, take your family and live abroad. You stop worrying about the right time. You will have five good years, you will have a crisis. The phoenix is symbolic of Lebanon — they try to bury us, we rise again.”

Mr Jreissati said he hoped a new electoral law would spur further positive change. Parliamentary elections have not been held since 2009, and the current parliament has extended its term twice. The law passed this year changes the system of representation in parliament that had been in place since 1960.

"I think as we head toward elections, we're going to see a lot of new faces, and we've been seeing that," said Habib Battah, the editor of Beirut Report news website.

“I think the state has failed to provide basic services; I don’t think the state has failed.”

Mr Battah said the ability to contest elections made Lebanon unique in the region.

“Lebanon remains the only place in the Middle East where you can really confront or criticise the government’s power ... It’s increasingly rare to find places in the region where you feel you can actually practise journalism.”

“People are very frustrated — but in the long-term politically, I’m optimistic. In the short term, I’m worried about the environment,” Mr Battah said.

“There’s corruption and vulture-like behaviour in much of the world and much of the Middle East, but Lebanon’s political class have turned the state into something that is there to serve their interests, rather than vice versa,” Mr Houry said. “It’s a true misunderstanding of economic liberalism.”

He said Lebanon’s current leaders might do well to look back to the presidency of Fouad Chehab, whose period of rule from 1958-1964 remains unique.

“He was the only president who tried to build up the state," Mr Houry said. “As a human-rights activist, it wasn’t fully rosy, but most of the state institutions and infrastructure are all from this era.”

In addition to elections, 2018 will likely bring other reckonings.

The government “thought that Costa Brava and the Dora landfills will last through 2020, they will barely last through 2018”, Mr Houry said, referring to the current main rubbish disposal sites. “I think what is interesting in the last few years is that the failure of the state is affecting a greater portion of the population, and in some ways the more affluent parts of the country.”

More: The World in 2017 - in pictures