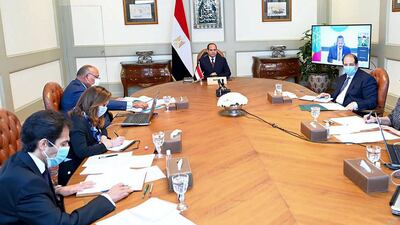

Egyptian President Abdel Fatah El Sisi wore a stern, maybe even angry, look during a videoconference summit called to find a resolution for a decade-long dispute over an Ethiopian Nile dam Egypt fears could impact on its life-and-death share of the river’s water.

The image of Mr El Sisi’s apparent displeasure, released by his media office, also showed Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed on television screens as he addressed the summit.

Hanging on the wall behind the Egyptian leader in a conference room was a framed Quranic verse often cited to comfort the faithful when in a predicament.

“With hardship there will be easiness,” reads the verse depicted in calligraphy and perhaps summing up the mood of the Egyptian leader as he strives to defend what the pro-government media in Cairo calls Egypt’s right to live against Ethiopia’s intransigence and recklessness.

After nearly a decade of protracted negotiations, Egypt has failed to persuade Ethiopia to commit to a legally binding agreement on the filling and operation of its Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, or GERD, and on a mechanism to ensure a sufficient flow of water to Egypt during multiple-year droughts. Proving elusive also is a standardised protocol to resolve future disputes.

Egypt depends on the Nile for nearly all its water needs. A reduced share of the Nile water could cost hundreds of thousands of jobs and disrupt its delicate food security. Mr El Sisi has said Egypt’s water share was an existential issue and that Cairo would never accept a status quo imposed on it. A general-turned-president, he never publicly spoke of military action to settle the dispute, although that option was never categorically taken off the table.

That intensely dreaded status quo, however, has been imposed on Egypt along with fellow downstream Sudan when Addis Ababa on Tuesday announced that the first-year target for filling its colossal dam was completed, a move Cairo and Khartoum have long insisted must not be made without an agreement in place.

That first filling is unlikely to reduce their share of water given the modest amount involved, but it constituted a dangerous precedent since Addis Ababa has said it intended to build a series of dams upstream, also on the Blue Nile, the main tributary of the Nile.

Tuesday night’s summit, chaired by Cyril Ramaphosa, the South African President and current chair of the African Union, followed the failure to produce a deal after nearly two weeks of talks this month by irrigation ministers and experts from Ethiopia and downstream Egypt and Sudan.

Ethiopia on Tuesday sought to inject a positive note in the gloom surrounding the negotiations, saying progress had been made on a deal to ease tensions with Egypt and Sudan. Mr Ahmed's office said the three nations had reached a “major common understanding that paves the way for a breakthrough agreement.” More talks were imminent, his office added.

The statement came as new satellite images showed the water level in the reservoir behind the nearly completed $4.6 billion dam at its highest in at least four years.

Mr Ahmed's office indicated that enough water had accumulated to enable Ethiopia to test the dam's first two turbines – an important milestone towards producing energy. The dam, which has become a national symbol to Ethiopians, is designed to produce 6,000 megawatts on completion, allowing Addis Ababa to provide electricity for the first time to 65 of its 110 million people.

A statement by Mr El Sisi’s office, meanwhile, emphasised Egypt’s “sincere will to continue to achieve progress over the disputed issues”.

The leaders, it said, agreed to “give priority to developing a binding legal commitment regarding the basis for filling and operating the dam.”

Sudanese Irrigation Minister Yasser Abbas said in Khartoum that once the agreement had been solidified, Ethiopia would retain the right to amend some figures relating to the dam’s operation during drought periods.

“Generally, the atmosphere was positive” during the talks, he said.

He also said that the leaders agreed on Ethiopia’s right to build additional reservoirs and other projects as long as it notified the downstream countries, in line with international law governing transnational rivers.

“There are other sticking points, but if we agree on this basic principle, the other points will automatically be solved,” he said.

Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and Ethiopia’s leader called Tuesday’s meeting “fruitful”.