It was in the summer of 2003, just after the US invasion of Iraq and ousted president Saddam Hussein’s escape, that Abdulrazzaq Al Saiedi sought to understand what Iraqis like him really thought about the former regime and what hopes they had for the country's future.

More than 17 years and seven governments later, to Mr Al Saiedi's dismay, people’s trust in the judiciary and its ability to hold people to account is still as low now as it was back then.

"The sense we got in 2003 from focus groups was at least that people were hopeful for what is to come," Mr Al Saiedi told The National.

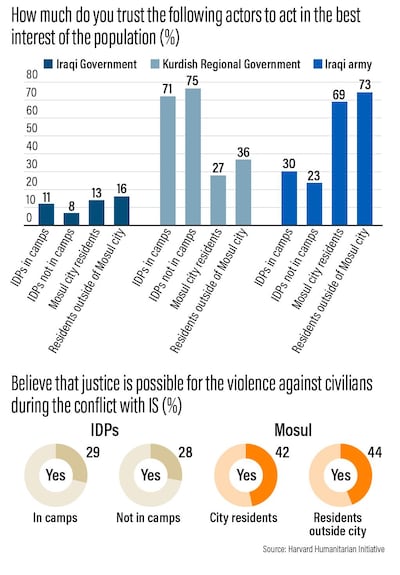

A survey last year of more than 5,000 people conducted by Mr Al Saiedi, shows sentiments have remained starkly the same across Mosul and among people who fled the northern city during the ISIS occupation.

“Despite the difference in demographics between the people staying in and around Mosul and internally displaced persons, this absence of trust was the common denominator,” he said in an online conference held to discuss his findings.

In the 2019 study, Mosulites said they trust the army more than IDPs did, most likely because of the military’s role in liberating Iraq’s second largest city from the grasp of ISIS in 2017.

Iraq then and now

In a 2003 debrief, while working with a human rights group, Mr Al Saiedi attended a coalition force briefing to discuss restoring electricity to the capital.

“They said there would be power shortages that year. It frustrated me to hear that people would not have electricity before the summer heat,” he said.

Now, electricity scarcity remains a painful sore and to Mr Al Saiedi, a reminder that the status quo has not changed more than a 15 years later.

An International Energy Agency report last year showed that power cuts occur daily even though available supply has increased by a third.

After leaving Iraq, Mr Al Saiedi worked as a journalist, a human rights officer and earned a master’s degree in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School at Harvard University in the US.

“People ask me about the US invasion and I tell them that we had won," he said.

"We won our freedom. But we lost our security.”

Yet without the fall of Saddam Hussein, Mr Al Saiedi and others like him would not have had the opportunity to report on Iraq’s realities.

“We had no freedom of the press; no ability to speak out against the government.”

Through his research, Mr Al Saiedi hopes that policy makers heed the public’s call for better governance and stronger trust.

“The era of ideology is over. Nowadays, people assess their governments on their ability to provide them with a decent and prosperous standard of living," he said.

Little has changed under Mustafa Al Kadhimi

The Iraqi people made their feelings about the state of the country clear when anti-government protests swept the nation in October last year. The ongoing demonstrations caused then-prime minister Adel Abdul Mahdi to resign in May. Hundreds of protesters were killed or injured in violent crackdowns carried out by the security forces.

The demonstrations brought Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al Kadhimi to power, but one year later, his government has made little progress in tackling the protesters' demands.

Basic services, electricity, jobs, an end to corruption and accountability for hundreds of civilian deaths are just some of the items on that list.

But for now, it remains uncertain whether Mr Al Saiedi will be getting the same responses from disillusioned Iraqis another decade from now.