Unkempt commercial buildings at the start of the main street in downtown Amman mark Jordan’s bookshop quarter.

The small area intersecting Al Salt and Saladin streets was once a busy destination for book lovers in the country of ten million, but the last two decades have seen a decline in reading.

Several major bookshops have closed as low demand hit the district, due to a smaller pool of readers and poor economic conditions, recently made worse by the impact of the coronavirus.

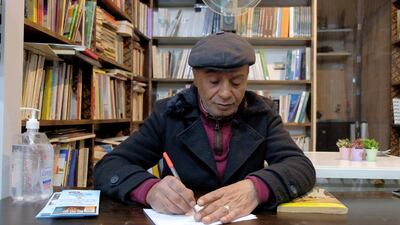

“We have not imported books in any real quantities in years,” says Nabil Al Muhtaseb, owner of one of the oldest bookshops in the district, which carries his family’s name.

He points to a drop in education standards affecting the country’s reading culture, and a younger generation of parents who do not encourage their children to read.

“Students stopped coming,” he said, attributing their absence to the scrapping of research requirements in most high schools in the 1990s and the halt of government support for a student book basket.

The decline is a reflection of political and social change in Jordan, where the last decade has been marked by economic stagnation and high unemployment that reached a record 23.9 per cent last year.

Despite the challenges, Amman’s book vendors are trying to re-establish a base by lowering their prices and advertising on social media.

A partial literary revival in the Middle East that accompanied the Arab uprisings from 2011 has inspired a generation of younger authors and helped bookshops in Amman mitigate loss of volume sales.

Many now give prominent positions on the shelves to the wealth of new works that emerged on the Arab uprisings for readers seeking fresh perspectives on the events of the last decade.

Literary legacy

Around the middle of the last century a common saying was: ‘Cairo writes, Beirut publishes and Baghdad reads.

Amman, meanwhile lacked the literary and educational prowess of Beirut, a city unshackled by the censorship imposed across the rest of the Levant.

But Jordan – a country carved from the remnants of the Ottoman Empire in the 1920s – developed into a somewhat diverse society made up of refugees and émigrés from Palestine, Syria and Iraq that helped keep its arts scene vibrant and varied.

Mr Al Muhtaseb’s ancestors founded his bookshop in Amman during the late 1940s, after arriving as refugees from the Palestinian city of Hebron in the West Bank.

Back then he had a lot of young customers, but now many prefer to spend their time online and gaming, he says.

A renewed demand has been created for novels in Jordan and across the region since the Emirates Foundation in Abu Dhabi set up a prize for Arabic literature modelled on the Booker Prize in 2008.

“It is a well marketed prize,” says Mr Al Muhtaseb, pointing to rows of novels on the main shelves in his store.

Like most bookstores in the area, the space is sparse and its neon lighting is outdated. The tiled floor and other fixtures show their age and could do with renovation. Unlike bookshops in Europe and the United States, there is nowhere to sit and flip through the volumes.

The selection is varied, from award-winning author Ahmed Saadawi's dystopian vision of US-occupied Iraq, Frankenstein in Baghdad to thrillers by American author Dan Brown, translated into Arabic.

But a main seller at Al Muhtaseb and other bookshops are mainstream religious books on Islam, reflecting a society that has become more conservative since the early 1980s.

Some customers still come looking for something more niche, including a class of Iraqis who fled to Jordan after the 1991 Gulf War that seek high quality and rare editions, especially books on Sufism, he said.

At Kunouz Al Marefa bookshop nearby, the shelves hold fiction works by Jordanian author Ayman Al Otoum, a former political prisoner and controversial author Salman Rushdie, but not his banned Satanic Verses.

On prominent display is Desire for a Parting, the latest work by Algerian novelist Ahlem Mosteghanemi who helped bridge a west-east divide in the region with her widely read works that examine human relationships in a politicised context.

Despite the emergence of the Gulf literary scene, with countries like the UAE promoting reading through festivals, competitions and organisations that encourage emerging writers, Mr Al Muhtaseb misses the books by Lebanese publishers that used to adorn his bookstore.

He no longer imports books from Lebanon because a well-to-do middle class that used to buy Lebanese books has withered.

“Lebanon is the king of the book,” Mr Al Muhtaseb said, pointing to a long literary heritage. A Lebanese monastery in Khinshara in the Metn Mountains is home to one of the first Arabic printing presses and the country has produced many of the Arab world’s most famous modern writers, including Amin Maalouf, Elias Khoury and Jabbour Douaihy.

A buyers’ market

At Al Raed, a multi-story bookshop with a large children’s section, a whole floor of books was marked for sale at one dinar each, or $1.40, in an attempt to clear stock from the warehouse.

The shop is run my Mr Al Muhtaseb’s nephew Raed, who likes the French writer Alexandre Dumas and books on chess.

He said the one-dinar sale helped bring in some new customers but not enough to sustain the business he inherited from his father, or restore the “special ritual” that once saw downtown goers make time to stop by the book district.

Hussein Yassin, a relative newcomer to the business has also had to drop his prices. He opened his bookshop in 2012 just outside the downtown area, in Jabal Amman, naming it Al Azbakeyeh after Cairo’s famed book district.

Mr Yassin, a former Jordanian student leader, started his business by borrowing the equivalent of $14,000 from a friend. He bought 100,000 books from a distribution agency that had changed ownership and bolstered his collection through donations.

“Books are my hobby,” he said. “Every day I receive donations from people in the form of books.”

Until the coronavirus, he set up stalls across Jordan, and sold copies at low prices or gave away books he received for free, in an individual effort to revive the reading culture.

He openly sells banned books, boosting the appeal of the bookshop to secular and politically inclined punters. Among them are books by Israeli historian Avi Shlaim and the late George Habash, founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and the Character of the Prophet, by late Iraqi poet Marouf Rasafi, whose work angered many clerics in the Middle East.

Around 70 per cent of his shop’s 115,000 Facebook followers are 18 to 25 year olds and the majority are women, statistics he finds “surprising given the rise in younger generations spending more time online.

However recent events have made life harder, even for Amman’s most successful book sellers. The impact of the coronavirus on the economy and consequent downturn in sales forced Mr Yassin to move to a much smaller shop in the same neighbourhood this year.

He is still buying books “but not like before” and he no longer travels to Egypt and India looking for cheap books.

But he is not to be deterred, attributing the decline “to the economy, not the people”. He has temporarily rented more space next door while preparing another makeshift stall to open in a few days, with books on sale for one dinar.

“The book should not die,” Mr Yassin said. “It is supposed to be re-read, to be given a new life.”