Personal items belonging to the renowned British theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking will go on public display at London's Science Museum next year.

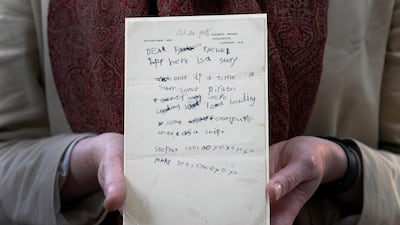

Objects to be exhibited include his speech synthesisers and a wheelchair, as well as letters he wrote to scientists and world leaders during his five-decade academic career.

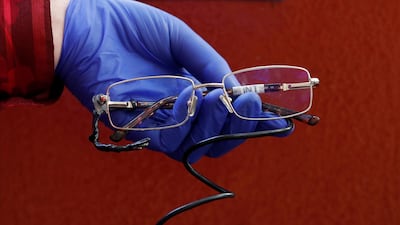

The museum will also display a pair of his glasses, which allowed him to communicate using an in-built sensor he controlled by twitching his cheek.

Mr Hawking, considered one of the greatest scientific minds of the last century, died in 2018 after suffering from motor neurone disease for most of his adult life.

The Science Museum Group acquired the contents of his archive under an agreement with Cambridge University Library.

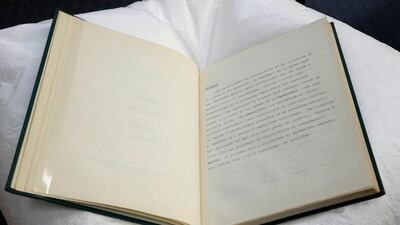

The £4.2 million ($5.9m) deal means 10,000 pages of Mr Hawking's scientific papers and other documents will remain at the University of Cambridge, where he taught and completed his PhD.

The archive, which includes documents dating from 1944 to 2008, including his academic papers and TV scripts from appearances on shows such as The Simpsons, will be housed alongside papers from Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin.

Hawking dedicated his life to unravelling the mysteries of the universe, particularly the nature of time and space.

His bestselling 1988 book A Brief History of Time popularised the scientific laws of the universe and the creation of black holes.

"We are very pleased that these two important institutions will preserve our father's life's work for the benefit of generations to come and make his legacy accessible to the widest possible audience," his children Lucy, Tim and Robert Hawking said.

"Our father strongly believed that everyone should have the chance to engage with science so he would be delighted that his legacy will be upheld by the Science Museum and Cambridge University Library."

University librarian Jessica Gardner said it was "profoundly important" his archive was preserved in Cambridge, "alongside the work of his hero, Newton, and so many other scientists".

"It's a really important part of the legacy," she said.