Northern Ireland marked its 100th anniversary on Monday as faltering efforts to commemorate the centenary encapsulate the rift at the heart of the British province.

Ever since Ireland was freed from British rule in 1921, Northern Ireland's existence has been controversial, and the knot in an often bloody tug-of-war between warring factions.

The province's troubled past, fragile present and uncertain future are disputed endlessly between pro-UK unionists and republicans who favour an alliance with Ireland.

Northern Ireland was created on May 3, 1921, when the island was split in two after the Irish war for independence.

"The centenary of Northern Ireland is by its very nature divisive, and it can't be anything but divisive," said Jonathan Evershed, a researcher at University College Cork.

Two weeks ago, black smoke from a burning roadblock billowed into the Belfast sky, symbolising the divisions overshadowing the centenary landmark.

As hooded youths hurled masonry, riot police poured out of rusty, armoured Land Rovers to form ranks.

All sides know their roles in this well-versed piece of street theatre, which provides the backdrop to the 100 years of the divided British province.

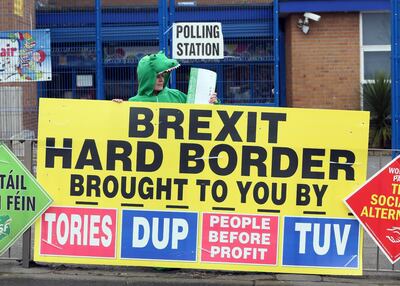

Scenes of unrest returned last month to Northern Ireland’s streets, the former battleground of ‘The Troubles’ where tempers are fraying over the fallout from Brexit and other tectonic political shifts.

At least 88 officers have been injured in clashes emanating from pro-UK loyalist enclaves, angry with a post-Brexit "protocol" they feel is casting them adrift from mainland Britain.

"All generations are angry and frustrated at what's going on," said David McNarry, of the Loyalist Communities Council.

"This damn protocol is a European invention to take away my Britishness," he said.

The focal point of much of the violence is at so-called "interfaces" where loyalist and pro-Ireland nationalist areas adjoin.

Towering "peace walls" separate communities, crisscrossing the Belfast landscape, a reminder of the divisions that remain even after The Troubles ended in 1998 with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

The latest violence saw loyalist youths face off with police who were preventing their advance towards a gate in the barrier.

In the early evening on April 19, teenagers covered their faces and scanned the ground for bricks and stones to throw.

A mother pushing a pram scooted her child out of the way as a small gang charged a police Land Rover, climbing on the bonnet, prying off a wing mirror and pulling at locked door handles.

Police on the front line remained inside their vehicles, their windscreens and sirens covered in metal grids that parried the worst of the debris.

Early in the evening, a switch pressed by an unseen hand slammed shut the gates in the "peace walls", completely sealing the neighbourhoods off from each other.

A convoy of police vehicles pulled in from a side street, parking in practised formation to block the road to the gates.

Ranks of riot police wielding batons and shields quelled the worst of the violence, for one night at least.

The unrest paled in comparison to clashes earlier in the month, when water cannon and dog units waged a running battle with gangs throwing petrol bombs and fireworks.

Loyalist and nationalist youths faced off in a night of disorder that shocked the UK and left the area by the peace gates charred and pockmarked.

A teddy bear has since been hung on the gates with a hopeful handwritten dedication: "Peace for our children's future."

Against this backdrop, it is hard to imagine a happy birthday for Northern Ireland.