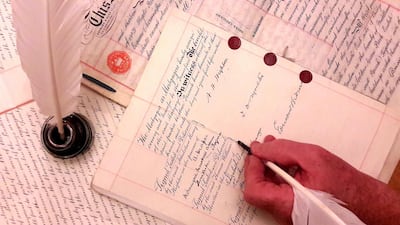

British lawyers may have used sheepskin for legal documents for centuries because of its unique anti-fraud qualities, a new study found.

Researchers examined 477 documents dating from the 16th to 20th centuries and found that most of them were written on sheepskin parchment, according to a new paper published in the journal Heritage Science.

The high fat content of sheepskin compared with pelts from goats and calves meant that any changes in documents showed up easily – making it harder to tamper with wills and land deeds.

Sheepskin was plentiful and cheaper, with between two and five million skins available every year over the centuries.

But evidence from the writings of judges and officials of the time showed that skins from sheep were preferred over alternatives and despite the growing use of paper.

One of the paper’s authors, Sean Doherty of the University of Exeter, said: “Removing fat during the parchment-making process can cause the layers within sheepskin to separate more easily than those of other animals.

“To make fraudulent changes to documents after signing, the original text would have to be scraped off. This could cause the layers within sheepskin parchment to separate and leave a visible mark on the document, resulting in the fraud being easily detectable.”

Academics found a document written by a senior royal official from the 12th century urging the king’s scribes to use sheepskins “for they do not easily yield to erasure without the blemish being apparent”.

Researchers took 645 samples from 477 property deeds from 1499 to 1969 and examined proteins from the parchment to identify the animal skin used. All but 23 were from sheep, while it was unclear from the remainder whether they were from sheep or goats.

The documents were considered of little historical value and many were turned into lampshades during the 20th century after a 1925 law meant they were no longer needed for claims on property.