England’s third national lockdown could last until March as scientists question whether the new measures will be enough to contain the runaway infection rate.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced the new stay-at-home order on Monday night as he revealed the health system was less than three weeks away from becoming overwhelmed by coronavirus patients.

Mr Johnson did not say when the lockdown would end but signalled a review would take place in mid-February.

Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove clarified on Tuesday morning that the relaxation of lockdown rules was tied to the pace of vaccinations.

He said the UK faced a “race against time” to vaccinate as many people as possible over the next few months before ministers can look at easing restrictions in March, taking into account the three-week lag for immunity to kick in after the initial injection.

Mr Gove's comments came hours before Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced a further £4.6 billion ($6.23bn) in fresh lockdown grants to help businesses survive the third shutdown.

“We can’t predict with certainty when we’ll be able to lift the restrictions," Mr Gove told Sky News.

"What we will be doing is making sure as many people are vaccinated as possible. As we enter March, we will be able to lift some restrictions, but not necessarily all.”

However, leading epidemiologist Prof Andrew Hayward said lockdown on its own may not be enough to bring the infection rate under control.

He called on the government to take a more proactive role by encouraging better compliance with the rules, especially in poorer communities, where people may have no choice but to go to work even if they are experiencing coronavirus symptoms.

"We need to do more than just stay at home and wait for the vaccine. We need to be actively bearing down on it," he told BBC's Radio 4 Today programme.

“What we need to do is empower local communities,” he added. “We should pay (organisations) to work with those communities to encourage testing, support isolation, shielding and encourage vaccinations.”

Mr Gove added that the UK was considering bringing in further rules for international travel.

Ministers are

The shutdown, which will become law on Wednesday morning, came as Britain expanded its vaccination programme by becoming the first nation to start using the shot developed by the Oxford University and drugmaker AstraZeneca.

Mr Johnson said people must stay at home again, as they were ordered to do during the first wave of the pandemic in March, because the new virus variant was spreading in a “frustrating and alarming” way.

“As I speak to you tonight, our hospitals are under more pressure from Covid than at any time since the start of the pandemic,” he said in a televised address.

From Tuesday, primary and secondary schools, colleges and universities will be closed for classroom learning, except for the children of key workers and vulnerable pupils.

University students will not return until at least mid-February. People were told to work from home unless it was impossible to do so, and to leave home only for essential trips.

All non-essential shops and personal care services such as hair salons will be closed, and restaurants can only operate takeaway services.

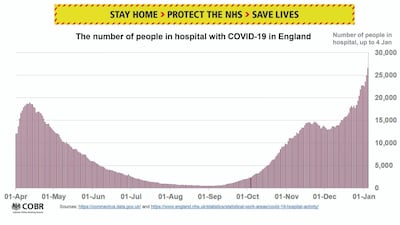

As of Monday, there were 26,626 Covid-19 patients in hospitals in England, an increase of more than 30 per cent from a week ago.

That is 40 per cent above the highest level of the first wave in the spring.

This chart shows how hospital admissions in the UK have shot up exponentially in recent weeks:

This chart follows the rise of patients in ventilation beds in hospitals across the UK:

Large areas of England were already under tight restrictions as officials try to control an alarming surge in cases in recent weeks, blamed on a new variant of coronavirus that is more contagious.

Authorities have recorded more than 50,000 new infections daily since passing that milestone for the first time on December 29.

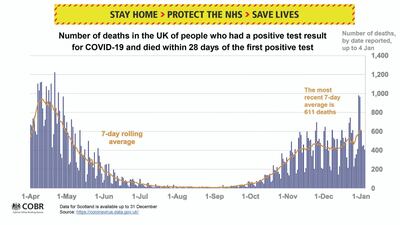

On Monday, 407 virus-related deaths were reported, pushing the confirmed death toll total to 75,431, one of the worst in Europe.

The UK’s chief medical officers warned that without further action, there was a “material risk” of health services being overwhelmed within the next three weeks.

Hours earlier, Scotland’s leader Nicola Sturgeon also imposed a lockdown with broadly similar restrictions. It will last from Tuesday until the end of January.

“I am more concerned about the situation we face now than I have been at any time since March last year,” Ms Sturgeon said in Edinburgh.

UK health authorities began injecting the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine around the country, fuelling hopes that life may start to return to normal by the spring.

“The weeks ahead will be the hardest yet but I really do believe that we’re entering the last phase of the struggle,” Mr Johnson said.

Britain has secured the rights to 100 million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, which is cheaper and easier to use than some rivals.

It does not require the super-cold storage needed for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

The new drug will be administered at a small number of hospitals for the first few days so authorities can watch for any adverse reactions.

Officials said hundreds of new vaccination sites, including local doctors’ offices, will open this week, joining more than 700 centres already in operation.

A “massive ramp-up operation” is now under way, Mr Johnson said.

The goal was that by mid-February, about 13 million people in the top priority groups – care-home residents, all those over 70 years old, front-line health and social workers, and those deemed extremely, clinically vulnerable – will be vaccinated, he said.

Brian Pinker, 82, a dialysis patient, received the first Oxford-AstraZeneca shot early on Monday at Oxford University Hospital.

“The nurses, doctors and staff today have all been brilliant, and I can now really look forward to celebrating my 48th wedding anniversary with my wife, Shirley, later this year,” Mr Pinker said.

But aspects of Britain’s vaccination plan provoked controversy.

Both vaccines require two shots, and Pfizer had recommended that the second dose be given within 21 days of the first.

The UK’s joint committee on vaccination, however, said authorities should give the first vaccine dose to as many people as possible, rather than setting aside shots to ensure others receive two doses. It has stretched the time between doses from 21 days to within 12 weeks.

While two doses are required to provide full protection, both vaccines provide high levels of immunity after the first dose, the committee said.

Making the first dose the priority will “maximise benefits from the vaccination programme in the short term”, it said.

Stephen Evans, a professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said policymakers were being forced to balance the risks of this change against the benefits in the middle of a deadly pandemic.

“As has become clear to everyone during 2020, delays cost lives,” Prof Evans said.

“When resources of doses and people to vaccinate are limited, then vaccinating more people with potentially less efficacy is demonstrably better than a fuller efficacy in only half.”

Monday’s urgent announcement was yet another change of course for Mr Johnson, who had stuck with a regional alert system that mandated varying restrictions for areas depending on the severity of local infections.

London and large areas of south-east England were put under the highest level of restrictions in mid-December, and more regions soon joined them.

But it soon became clear that the regional approach was not reducing the spread of the virus, and critics have been calling for a tougher national lockdown.

While schools in London were already closed due to high infection rates in the capital, Mr Johnson had said students in many parts of the country could return to classrooms on Monday after the Christmas holidays, to the dismay of teachers’ unions.

“We are relieved the government has finally bowed to the inevitable and agreed to move schools and colleges to remote education in response to alarming Covid infection rates,” said Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders.