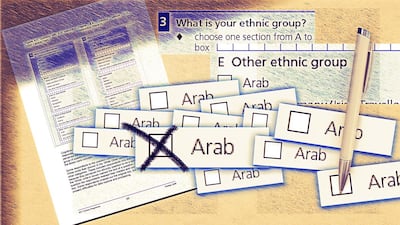

Arab residents in Britain have been urged to stand up and be counted amid fears that this year’s census could represent a missed opportunity to provide a comprehensive map of a community that has evolved rapidly in recent decades.

Since the first national census began in 1801 UK residents have given details about how they live, love, work and self-identify, but it took 210 years for Arabs to make a mark.

However, experts warn that a single tick box fails to properly gauge the scale and diversity among the Arabic-speaking community, some of whom do not ethnically identify as Arab.

Without a broader understanding of the nuances of culture and terminology, valuable opportunities to ensure they are not marginalised might be missed.

Nevertheless, the 2021 census, which is going ahead in England and Wales despite current coronavirus restrictions, will provide unprecedented data on the Arab community. For the first time there will be data to compare with the 2011 census results.

Should Arabic speakers tick ethnicity box in census?

Chris Doyle, Director of the Council for Arab-British Understanding, says it is essential people within the Arabic-speaking community fill the census and tick the box -- not just those who see themselves as very definitely Arab.

"It's in the interest of these communities to widen representation," he tells The National, "not for nefarious reasons but for needs assessment, to ensure those communities aren't marginalised, to help with inclusion [and also] so new arrivals can settle in well."

It is a legal obligation for people in the UK to fill out the census which is being conducted in the fourth week of March. Experts in social trends believe that concerns around data-gathering, misidentification and the absence of suitable categories mean not everyone is happy to do so.

The England and Wales 2011 Census showed a total of 366,769 people ticked the ‘Arab’ box or provided a write-in response.

Demographers believe this number represented a bare minimum, given evidence that the categories were misunderstood by a substantial number of respondents.

The census form did not record any breakdown in the numbers. The proportion of people born in the UK or other countries who identified as Arabs is not known in relation to first-generation Arabs, much less data on ‘mixed Arabs’ – where only one parent is an Arab.

The term ‘Arab’ itself is problematic as not everyone from an Arabic-speaking country identifies with the categorisation -- Amazighs, Berbers, Copts, and Yazidis, to name just a few existing ethnicities within the Arab world. There are also many who speak Arabic or come from countries in the Arab League who would not classify themselves as Arab.

For those who take issue with the Arab categorisation, the census does collate information on languages spoken, including an Arabic option.

This could help determine the size of the community, but of course not everyone with origins in the region necessarily speak the language, particularly those who are of mixed and first-generation heritage.

Census helps government in allocating resources

The census is an important tool in providing valuable population information to help councils and governments plan services. Without accurate data on the make-up of a community, their needs may be side-lined and resources allocated elsewhere.

“If an MP or mayor doesn’t know the make-up of community then it will remain marginalised,” says Mr Doyle, whose organisation produced a report on British-Arab communities that included a critical assessment of the 2011 Census.

The increasing wariness of people on matters of security and data-gathering has also had an impact on the way people view the census. This can sometimes be compounded by experiences of repression and discrimination, whether in their country of origin or in the UK.

British-Arab communities remain severely under-researched and Mr Doyle said that more knowledge on the community is crucial to ensure their visibility and empowerment.

“We don’t all belong in nice easy boxes so we have to take these censuses as they are and use them to our advantage,” he says.

Roshni Goyate, co-founder of The Other Box, an organisation that provides diversity, equity and inclusion training, agreed. She said while they are a necessary part of the discourse on inclusivity, categorisations fail to take into account the fluidity of identity and people’s unique circumstances.

"The Arabic speaking community is such a diverse group of people -- to tick just one box deletes all of that nuance," Ms Goyate said. “If we think about the Arabic speaking community, there's such a diverse group of people, even within London, let alone the whole of the UK.

"And then the political situations, their reasons for coming to the UK as immigrants are so varied and diversified that having to tick just one box deletes all of that nuance, which is in itself problematic, especially in the times that we live in now with the Islamophobia and racism prevalent in the UK.”

Census can counter negative British-Arabi stereotypes

Nevertheless, Mr Doyle said that even if one accepts that British-Arab communities are fragmented on national, ethnic or religious lines, the people who discriminate against them see them as a unified whole.

"This is reason enough to unite under a British-Arab identity to counter negative stereotypes and marginalisation," he tells The National.

Ms Goyate understands the importance of having solidarity and critical mass in developing inclusivity but believes designations must go hand in hand with transparency and education.

"I think whoever is in charge of these boxes and forms must also communicate with awareness that they understand boxes are problematic. But these are the functions that the boxes serve at the moment," she tells The National over Zoom.

When it comes to the companies Ms Goyate trains, she always advocates for write-in responses that allow people to make their own declaration, no matter the challenges this poses for categorisation by the statisticians.

Regardless of the shortcomings, data increasingly rules the allocation of resources and there is undeniably strength in numbers. In the coming years, the national statisticians will be advising the government on whether to abandon the national census altogether for more regular and cheaper updates from a variety of sources.

The forthcoming census exercise could well be the last opportunity to stand up – or in this case fill in – and be counted.

Census 2021: Five reasons why Arabic speakers should take part

1. The ethnic category exists

2. Widens representation and allocation of resources

3. Provides comparative data

4. Shows trends among the Arab population

5. Increases awareness on Arabs and reduces marginalisation