Turkey’s doctors are leading a rush of people leaving the country amid economic turmoil and what medics say are deteriorating conditions and growing violence at work.

About 2,700 doctors applied for good conduct certificates to allow them to seek work abroad last year, nearly double the number for 2021, according to the Turkish Medical Association, or TTB.

The association says the rate of doctors leaving the country has increased 70-fold over the past 11 years.

Medics across Turkey went on strike earlier this month, protesting against long-hours, poor pay and rising levels of violence facing hospital staff.

Many are choosing to search for jobs in Europe and North America where they can command salaries up to three times higher than in Turkey.

“There’s a lack of personal benefits and the salary is low considering the work doctors carry out [in Turkey],” said MG, 34, a physician who recently moved to Germany. “Shift rates are so low as to be insulting.”

MG asked for his name not to be used to avoid problems with the authorities when he travels back to Turkey.

He cited failure to address the rise in workplace violence and the lack of value given to medical professionals as reasons for leaving.

“The number of patients is very high and the referral chain doesn’t work – everyone just comes to hospital as they see fit and patients’ relatives just wander in.”

MG – now working in psychiatry in Germany – said wider societal issues also influenced his decision, such as high inflation, social polarisation, restrictions on personal freedoms and growing anxiety for the future.

“Seeing such problems in my own country demoralises and demotivates me,” he said. “Even if I am discriminated against in another country, I cannot stand experiencing these issues in my country.”

TTB general secretary Vedat Bulut said more than one in eight younger health professionals, including nurses, technicians and other health workers, favoured working abroad because of poor conditions in Turkey.

Older staff, many of them highly valued specialists with years of experience, are seeking foreign jobs to raise their earnings.

“They also say they don’t see any future in Turkey due to changes in society,” Dr Bulut said.

The migration of doctors is reportedly leaving large gaps in healthcare services in Turkey. Shortages in specialist fields such as oncology, rheumatology and paediatric neurology are particularly acute, said the TTB.

“Many hospitals don’t have these sub-specialists, people who have a high level of expertise and are in high demand overseas,” Dr Bulut said.

“Even accounting for the differences in the cost-of-living, they can earn two to three times more abroad than what they get in Turkey.”

High on medics’ concerns is the violence directed against health workers, usually when patients or their relatives are frustrated by long waiting times or what they perceive to be inadequate treatment.

A January report from the Health and Social Service Workers’ Union said 422 staff were subjected to violence last year, despite new laws that increased the penalties for attacking health personnel.

A cardiologist in Konya, central Anatolia, was shot dead in July last year by a man who blamed the doctor for his mother’s death.

In the most recent publicised attack, an ophthalmologist was beaten by two men in Izmir, western Turkey, on Monday over the results of an eye test.

The medical profession has also been under political pressure. The TTB’s president was convicted of a terrorism offence in January, having called for an investigation into claims about the use of chemical weapons in northern Iraq, where Kurdish militants have tried to establish a border sanctuary, amid raids by the Turkish army.

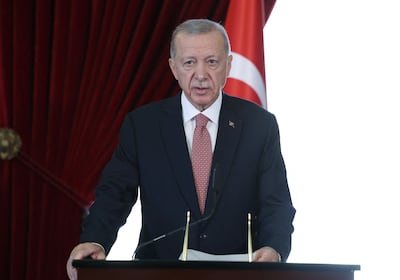

During the Covid-19 outbreak the association faced calls for its closure – led by ultranationalist leader Devlet Bahceli, a key ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan – over its criticism of the government response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Following reports of medics leaving Turkey due to poor pay and working conditions in March last year, Mr Erdogan responded by saying: “Let them leave.”

Within days he backtracked, promising health reforms and urging doctors to “shift back … to their own country”.

Asuman Dogan, a physical therapist and board member of the Ankara Chamber of Medicine, said frequent organisational change in the health system led to job insecurity while even doctors in the private sector “struggle to make ends meet”.

“Physicians are frustrated by these problems, by hard working conditions, drudgery and mobbing,” she said. “They are experiencing burnout and frustration.”

Ankara-based family doctor Umit Yasar Oztoprak described the “desperate mood” among staff in family health centres due to the “daily routine” of verbal and physical violence, a lack of time for patient consultation and the threat of malpractice lawsuits, among other issues.

Meanwhile, wider migration from Turkey shows up in official Turkish and European figures.

The Turkish Statistical Institute reported that 139,531 Turkish citizens left the country in 2022.

The EU received 58,000 first-time asylum applications from Turkish citizens last year, up from 20,315 in 2021, the European Commission’s Eurostat agency said.

Most applicants wanted to move to Germany, where authorities reported a 203 per cent annual leap in the number of asylum claims from Turkey in the first seven months of 2023.

The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees said about 23,850 Turks applied for asylum, the third-largest national group behind Syrians and Afghans.

And in the UK, which signed an immigration deal with Ankara last week, the Home Office said some 1,360 Turkish citizens were caught crossing the English Channel between April and July. The figure for the whole of 2022 was fewer than 1,100.

In a recent interview with the Sozcu newspaper, the EU’s Turkey representative, Nikolaus Meyer-Landrut, said there were 778,000 visa applications from Turks last year, the highest for any country.

He also revealed for the first time that Turkish students studying in Europe had applied for asylum at the end of their courses.

But it is the flood of expensively trained medical staff that is most worrying.

Dr Bulut said he expected around 3,000 doctors to leave this year. Turkey has about 180,000 doctors in total.

“Many of these people are highly qualified doctors so when they leave, the health system in Turkey suffers disproportionately,” he said.

“In four or five years, we will see many people unable to reach the health services they need. We will have to spend more to treat people because of delays and there will be a rise in preventable deaths.”