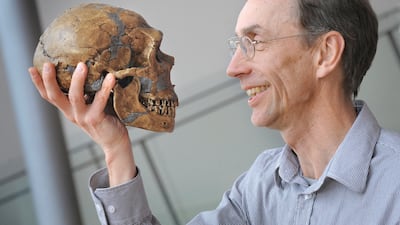

Swedish geneticist Svante Paabo on Monday was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine for his groundbreaking work on the genome of humanity's extinct relatives, including the Neanderthal.

Here, The National explores Dr Paabo's past and explains why his work is so significant to modern-day medicine.

Who is Svante Paabo?

Dr Paabo was born in Stockholm in 1955 and earned a doctorate at Sweden's Uppsala University.

He became a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Zurich and later at both the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Munich.

In 1999, he founded the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. He also currently holds the position of adjunct professor at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan.

He is the son of Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Sune Bergstrom, who in 1982 was recognised for his work on prostaglandins and related substances.

Who is Linda Vigilant?

In Dr Paabo's 2014 book Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes he declared that he was bisexual and had assumed he was gay until meeting US primatologist and geneticist Linda Vigilant at the University of California.

He said her “boyish charms” attracted him to the extent they married and had a son and a daughter, whom they are raising in Leipzig.

Dr Vigilant is now a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute in the department of primatology. Her specialism is genetic analysis of wild primate populations.

Why did Paabo win the Nobel Prize?

Dr Paabo overcame the technical challenges resulting from the degradation of DNA over tens of thousands of years and became one of the founders of palaeogenetics,

The Nobel Committee said Dr Paabo had “accomplished something seemingly impossible: sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal, an extinct relative of present-day humans”.

London's Natural History Museum said Neanderthals are “our closest ancient human relatives”, with “Neanderthal and modern human lineages separated at least 500,000 years ago” — although the date of the divergence has also been estimated to have occurred about 650,000 years ago.

Neanderthals and early modern humans lived alongside each other for part of their existence, though there is evidence of some interbreeding, as humans today have inherited about 2 per cent Neanderthal DNA, according to the museum.

“[Paabo] also made the sensational discovery of a previously unknown hominid, Denisova,” the Nobel Committee said, referring to his breakthrough after examining a 40,000-year-old fragment of a finger bone found in Siberia.

Denisovans were an archaic Asian people first identified in 2010 by Dr Paabo and fellow scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.

The findings were based on mitochondrial DNA the scientists extracted in 2008 from a juvenile female finger bone excavated from Denisova Cave in Siberia's Altai Mountains in 2008.

Dr Paabo and his colleagues concluded that Denisovans descended from an earlier migration of Homo erectus out of Africa and were probably in existence from anywhere between 50,000 to 400,000 years ago.

What is the significance of Paabo's work?

Having discovered this ancient flow of genes to present-day humans, Dr Paabo's work has the potential to transform scientists' physiological understanding of present-day humans, particularly how the human immune system reacts to diseases ranging from schizophrenia to severe Covid-19.

“The fact that a good fraction of the people running around in the world today have DNA from archaic humans like Neanderthals is of important consequence to who we are,” said David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“So I think that knowing that and trying to understand the implications of that for health is something that will be with us for the rest of our the rest of our time as a species.”

Chris Stringer, a palaeoanthropologist at the NHA, said that Dr Paabo's findings had revolutionised our understanding of the past and were “central to human evolutionary studies”.

His verdict endorsed the assessment made by the Nobel panel.

The findings “opened a new window to our evolutionary past, revealing an unexpected complexity in the evolution” and provided “the basis for an improved understanding of genetic features that make us uniquely human”, Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam and Anna Wedell of the Karolinska Institute wrote for the Nobel Assembly.

How much did Paabo get for winning Nobel Prize?

Dr Paabo received 10 million krona ($900,000) upon winning the award.