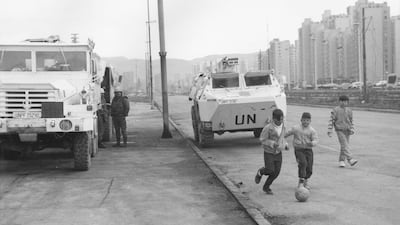

For the past three decades Bosnia has largely enjoyed peace after the horrors of the civil war that caused 100,000 deaths, the majority from the Muslim community.

But the country is now in danger of sinking into ethnic violence again with a bombastic campaign driven by ethnic Serbs attempting to break away.

Bosnia is on a “dangerous path” the UN Security Council heard this week.

Experts told The National that the country could again “come apart” with the increasingly desperate Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik pushing for a split.

Tension is rising among the country’s two million Muslims who are terrified at the prospect of a return to the genocide of the 1990s.

Mr Dodik’s secessionist campaign could inflame ethnic tensions in the country, which is made up of Muslims, Serbs and Croats, who have managed to co-exist in relative peace in the two largely autonomous regions of Republika Srpska (Serbia) and the Federation of Bosnia.

“If this does expose Bosnia to be that fragile, then a lot of other things could start to come apart,” said Prof Michael Clarke of the Rusi think tank.

Alarm is also growing in the international community, particularly after a pronouncement by Mr Dodik to split Serbs from the multi-ethnic Bosnian army.

Bosnia was at “critical juncture in its post-war history” the US ambassador to the UN, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, told the Security Council on Wednesday. “The heated rhetoric must stop,” she said. “Milorad Dodik has called for the Republika Srpska’s withdrawal from the armed forces and from state-level institutions … this is a dangerous path.”

That path could lead to the 700-strong European Union peacekeeping force (Eufor), that polices the 1995 Dayton Accords, being rapidly reinforced to compel the Serbs to disarm.

“You could see a scenario where a dispute between Republika Srpska and the Bosnian Federation could lead to the Bosnian Serbs withdrawing from the multi-ethnic Bosnian Army and effectively setting up their own army,” said Brig Ben Barry, of the International Institute of Strategic Studies. “Now that would pose a very, very difficult question for Nato and the EU.”

The former British Army officer, who commanded an infantry battalion in Bosnia during the 1992-1995 civil war, said that Eufor was too small “to coerce the Bosnian Serbs” into disarming.

“Things could quickly get worse and the EU could be forced to make a judgment that this has gone so far outside the Dayton Accords that it must take military action compelling the Bosnian Serbs to desist from their course of action,” he said.

A tinderbox legacy exists in Bosnia, particularly with the aggressive Serb militias in their enclaves in the north and east of Bosnia, said Balkans expert Dr Jessie Barton Hronesova.

“There are still some paramilitaries that exist and there are some still some maniacs around the region,” the Chatham House think tank academic told The National.

“These are right wing, Serb nationalist organisations, that have their own militia and vigilantes. If they really got into some serious fights that the state was not able to deal with then the EU or someone would be invited to intervene.”

Whether the EU and Nato, which have the legal sanction to take unilateral military action, have the stomach for a strong military intervention is questionable given recent failures.

“The danger is that there'll be no appetite from the West this time to send forces in to hold it together because of the Iraq and Afghanistan legacies,” Prof Clarke said.

In previous contingency planning, four Nato infantry battalions were in a state of high readiness to deploy to Bosnia and enough combat aircraft “to make the sky go dark”, according to Brig Barry. It is understood that planning is being updated.

Concerns are being driven after Christian Schmidt, the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina, said in a confidential report this week that the country faces “the greatest existential threat of the post-war period”.

While this has created alarm there is still disbelief in Bosnia that the barbarism of the 1990s might return. “I simply don't think anyone really believes that this could flare up in really large scale conflict,” Dr Barton Hronesova said.

But it was having an unsettling effect among the 1.8 million Bosnian Muslims who suffered more than 60,000 deaths in the civil war, including the Srebrenica atrocity in which 8,000 Muslim men and boys were executed by Serb paramilitaries.

“The Muslim population is very concerned, but I think there is also a little bit of complacency too as Dodik has been doing this for quite a while,” Dr Barton Hronesova said.

Prof Clarke believes it is a difficult moment for them. “This is terrifying for the Bosnian Muslim population [who] have a real problem, because even with all of our help, they've only just about been able to hold the country together,” he said.

This comes from the desperate politics of Mr Dodik, 62, attempting to cling on to his shrinking powerbase in the northern Bosnian city of Banja Luka.

The political leader since 1996 was once regarded as a moderate, but has increasingly become more nationalistic, invoking the right of Bosnian Serbs to self-determination, using rhetoric such as “RS exit” (Republika Srpksa) to gain a similar legitimacy as did Brexit.

While he has some support from Russia and Serbia, it is thought that he is deliberately stoking the nationalist flames to remain in power and out of jail.

“He knows that the moment he's out of politics he's probably in prison or in exile,” said Dr Barton Hronesova, who previously worked for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

“He's meant to be the defender of the nation within Bosnia and Herzegovina, but he's just the defender of himself,” she said. “He's basically saying that within the next six months we're going to secede, and we need to take all of these steps in order to do so. He's struggling for his political life and taking an extremely dangerous, interest-based high-stakes gamble.”

Mr Dodik also suggested that if his people were attacked then Russia would assert its right to defend fellow Slavs.

That might be overplaying it as President Vladimir Putin is unlikely to get overtly involved in the Bosnia conflict because there will be little reward, unlike his land grabs in eastern Ukraine or Crimea.

But Moscow may also sense an opportunity to undermine Nato in the Western Balkans, as it has done in Northern Macedonia and Montenegro.

“This could go in an unwelcome direction because the Balkans have become an arena of competition between the EU, Nato and Russia,” said Brig Barry. “If Serbs are forcibly disarmed, which is one of the things that would have to be done, Russia’s reaction could be problematic.”

The brewing conflict comes at a time when neighbouring Serbia is re-arming its military with new helicopters, tanks, drones and missiles after a 70 per cent increase in its defence budget since 2015 to $1.4 billion a year. There is also a growing aspiration for a “Serbian World” which others in the region fear is code for a “Greater Serbia”.

But Belgrade is unlikely to risk its position with Brussels while it is in talks to join the EU. A new conflict would probably be unpopular and there are elections in April.

Outside the fiefdom of Mr Dodik, the desire for war appears low, but enmity remains and events could take an unforeseen and violent turn.

“It’s all very hard to predict,” said Dr Barton Hronesova. “I do not want to devalue the seriousness of this because it is extremely serious, but I really cannot believe that a conflict is on the cards.”