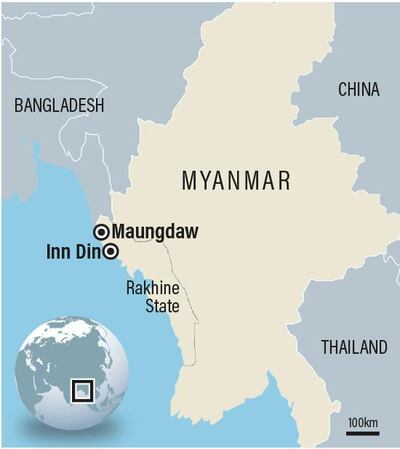

A narrow dirt path runs through the village of Inn Dinn, in northern Rakhine state in Myanmar. On the western side, 900 Rakhine Buddhists live, farm and worship at a large pink monastery. To the east is an overgrown tangle of brush and burnt trees.

A Buddhist woman drinks tea in her yard, which overlooks the remains of charred huts. “There was a fire,” she says, but she doesn't know who started it.

What happened in Inn Din has been well documented. A report released in August by a UN Fact-Finding Mission established how during a Myanmar "clearance operation" in September 2017, soldiers shot and stabbed villagers, raped women, and burned homes while driving 6,000 ethnic Rohingya from their homes.

A Reuters investigation in February detailed the murder of 10 Rohingya men and boys at the hands of Myanmar troops, police officers and Rakhine Buddhist villagers on September 2, 2017. The Myanmar government corroborated this report when it sentenced seven soldiers involved to 10 years imprisonment.

But on a recent government-controlled press tour of Rakhine, there is no acknowledgment of the massacre of Inn Din, or of other events last year, when 700,000 ethnic Rohingya were driven from their homes in a state-sponsored campaign of ethnic cleansing that left 10,000 dead and was described by the UN Fact-Finding Mission as genocide.

Instead, the first tightly controlled visit to the state since the UN mission announced its findings reveals how in the past year, the Myanmar government and the passage of time have conspired to destroy evidence of this genocide. In its place an entirely different narrative has been constructed in the minds of the remaining, mostly Buddhist locals.

While memory of the Rohingya’s patrimony is being erased in Rakhine state, it remains compelling and vivid in the minds of Rohingya refugees living in exile in southern Bangladesh. And it is their eye witness testimony of ethnic cleansing, experts suggest, that may one day be sufficient basis for international war crimes prosecutions.

Long before last year’s campaign of mass displacement and destruction, the Myanmar government had subjected its Rohingya people to systemic persecution. Since the Rohingya are Muslim and speak a language similar to the Chittagonian dialect of southern Bangladesh, Myanmar's government and much of its Buddhist population consider them illegal “Bengali” immigrants. They cite this belief to justify denying the Rohingya citizenship, education, and the right to travel freely.

Rohingyas, however, are native to the land that Myanmar calls Rakhine state – a land that was inhabited by their ancestors long before it was crudely divided into two British colonies that later became Muslim-majority Bangladesh and Buddhist majority Myanmar.

Hatred of the Rohingya has intensified in the years since Myanmar opened its doors to international aid and investment, as Rakhine Buddhists, who are outnumbered by the Rohingya in northern Rakhine state, see themselves as receiving less assistance. Powerful Buddhist nationalist groups have capitalised on this resentment, creating a climate in which politicians can score points by appealing to Buddhist nationalism.

When a group of poorly armed Rohingya insurgents known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) launched a series of attacks on security installations in Rakhine state on August 25, 2017, Myanmar’s military responded with a campaign of unprecedented violence. According to the UN Fact-Finding Mission, “the nature, scale and organisation of the operations suggests a level of preplanning and design on the part of the Tatmadaw [military] leadership."

The Tatmadaw's commander Min Aung Hlaing stated at the height of the operations: "The Bengali problem was a long-standing one which has become an unfinished job despite the efforts of the previous governments to solve it. The government in office is taking great care in solving the problem.”

The nature and the scale of this apparent genocide campaign, recounted in grisly detail by Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh to the members of the UN mission, are no longer evident in the landscape of Rakhine state. The government has bulldozed the remains of Rohingya villages and built new ones in their place, inviting non-Rohingya to settle there. Ruins are enveloped by foliage, covering nearly every trace of last year’s atrocities. Through a combination of concealment and neglect, Myanmar authorities have transformed their crimes scenes into a land of alternative facts, where physical evidence of crimes has been destroyed, and the history of the Rohingya has been erased.

In Inn Din, village administrator Kyaw Soe Moe denied knowledge of the mass graves documented by Reuters and confirmed by Myanmar’s imprisonment of seven soldiers. “I haven’t heard of any mass graves here.”

Other villagers, and security forces, likewise denied knowledge, consistently replying: “I’m not from here,” or “I wasn’t here at the time”.

This is apparently a deliberate government policy, says Matthew Smith, the chief executive of Fortify Rights, one of the main groups documenting Myanmar’s crimes against the Rohingya. “The authorities routinely cycle people in and out of sensitive areas. This could be a tactic to suppress the truth.”

Fifty kilometres up the coast, in the district capital of Maungdaw, the charade continued. The reporters were ushered into a brightly lit conference room in the office of the General Administration Department – a powerful administrative body controlled by the military. Three local officials flicked through PowerPoint slides showing the bloody remains of people they claimed had been killed by “Bengali terrorists”. The military has been caught on several occasions staging photos of crimes allegedly committed by Rohingya or falsely captioning photos taken elsehwere to support its narrative.

“No police, no military forced people to flee. Only ARSA did,” said Maungdaw Township administrator Myint Khaing. “Genocide never happened in our country and never will happen.”

Blaming the flight of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees on ARSA is a crucial element of Myanmar’s strategy to avoid accountability. The country continues to maintain that its troops did not deport anyone and that “Bengali terrorists” ordered Rohingya villagers to burn their own homes and flee to Bangladesh in an effort to frame Myanmar.

Despite their best efforts at suppressing evidence, such as the jailing of the Reuters journalists who exposed the Inn Din massacre, contradictory evidence continues to emerge. A recently published video filmed in August 2017 shows a scene of apparently premeditated deportation. The video shows a Myanmar soldier instructing a group of non-Rohingya villagers to "clear out" Rohingya villages with sticks and swords. The soldier can be heard saying: "Slowly and step by step, [Rohingya] want to take the whole Rakhine State. Then, they will conquer the whole country…We'll clear out their villages soon after we leave here."

Maungdaw District administrator Ye Htoo responded to the video in the same way many Myanmar officials do when confronted with proof of wrongdoing: “I have no comment, but if it’s true, the military will take legal action.” But justice so far has been reserved for low-level offenders, who are scapegoated to forestall the threat of accountability for the clearance operations’ high-level organisers, who allegedly include Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

_______________

Read our special report on displaced Rohingya Muslims in Cox's Bazaar, Bangladesh:

'I saw them with our women, doing whatever they wanted'

For the Rohingya, now at least, anger stops short of militancy

Rohingya find their voice in exile but not an audience

How the exiled Rohingya and endangered elephants learnt to coexist

_______________

Myanmar’s efforts to erase evidence in Rakhine state indicate that the government of Aung San Suu Kyi has no intention of pursuing justice for the Rohingya, even though the military orchestrated and carried out its genocidal operations without the consent or oversight of the civilian government she leads.

Rights groups now pin their hopes for accountability on international bodies. The most likely organisation to rule on the alleged crimes of Myanmar military leaders is the International Criminal Court. Absent a request by the UN Security Council, the ICC ordinarily only has jurisdiction over countries that have ratified the Rome Statute. Myanmar is not a member, so in order for the court to investigate the crimes in Rakhine state, prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has argued for jurisdiction on the basis that Myanmar's forced deportation of Rohingya took place in part on the soil of Bangladesh, which is a member. The court agreed with the argument and announced on September 6 that it does have jurisdiction to investigate Myanmar's alleged deportation.

Ms Bensouda is conducting a preliminary examination of last year’s clearance operations in order to determine whether a full investigation is warranted. An indictment would be made on the basis of that investigation.

According to Hollie Nyseth Brehm, a genocide scholar at Ohio State University, “even if the ICC were to indict suspected perpetrators, international criminal trials are slow moving at best”.

Fortunately, Myanmar's destruction of physical evidence would not necessarily be a barrier to prosecution. "Some courts, like Rwanda's post-genocide gacaca courts, relied almost exclusively on eye-witness testimony," said Ms Nyseth Brehm. "We know that eye-witness testimony is certainly flawed, but in the absence of other forms of evidence, it may be the only option."

Wayne Jordash, a lawyer for the firm Global Rights Compliance, which is representing a group of Rohingya sexual assault survivors who have petitioned the ICC to investigate gender-based violence as a component of genocide, agrees that a lack of physical evidence is not the greatest obstacle. “The problem is not establishing whether hundreds of thousands of Rohingya were deported or persecuted or even [subjected to] genocide. The bigger problem is whether we’ll find the linkage witnesses... Every international trial relies on insider witnesses who have generally got a lot of blood on their hands themselves but are persuaded, cajoled, or coerced by the prosecution to assist their aims by giving evidence and pointing the finger within the organisation.”

On September 27, the UN Human Rights Council called for the establishment of an “independent mechanism” that will collect and preserve evidence, especially the type that could link crimes against the Rohingya to specific perpetrators, to be used in a future prosecution.

That same day, the journalists on the media tour in October made their last stop at the fence 10-foot fence that separates Myanmar from a strip of land on the Bangladesh border known as No Man’s Land. Here, more than 5,000 Rohingya refugees subsist on food delivered by the Red Cross. Speaking through the fence and flanked by dozens of fellow refugees, a community leader named Dil Mohammad explained that he and his people will not return to Myanmar until a number of demands are met: a guarantee of safety, the right to citizenship, and accountability for the people who drove them from their homes and destroyed their villages.

“The ICC must put the perpetrators on trial,” he said. “If they try, it can happen in a short time. We are hopeful.”