As India’s Covid-19 crisis deepened in March, students were filled with dread at the prospect of yet more remote learning and patchy support from staff.

Most had already realised that their own health, as well as that of relatives, was at risk from a ferocious strain of the virus.

The crisis has piled mental strain on students in higher education in India, of whom there are about 37.4 million.

Studying amid grief

Three weeks ago, on a hot Delhi summer afternoon, Tanisha (not her real name) was scouring social media for leads to procure remdesivir, an antiviral drug commonly prescribed to treat Covid-19.

Her grandmother was in hospital with the illness, but her condition was deteriorating.

The hospital had run out of stock. “I tried my best, but couldn’t get it,” Tanisha said. “By 5pm, we had lost her.”

With her family grieving, Tanisha’s first thought was about the approaching deadline of her incomplete assignment, due to be submitted within 36 hours.

She sent a text message to her university lecturer in Bengaluru, informing him about the death and asking for more time for the assignment.

“I lost my grandmother, I don’t feel like doing anything. I don’t know if I will be able to submit my assignment on time,” she wrote.

“I’m sorry. I don’t feel like doing anything either,” he replied, without a word on an extension.

Tanisha didn’t know what to make of it and told him she would try to submit her assignment on time. A friend completed it for her.

Like most university students worldwide, Tanisha, 20, must juggle coursework and exam preparation.

But in India, the workload is accompanied by the knowledge that the pandemic is placing more strain on the country’s crumbling healthcare system.

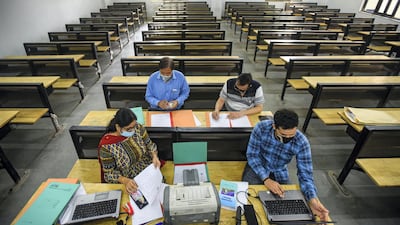

Unprepared universities

Seemingly unaware of the heightened pressure being experienced by students, some of their supervisors are being inflexible with assignment deadlines.

They have little faith that students will not cheat in online examinations and are giving them extra assignments, to grade them accurately.

By Wednesday morning, India had reported 25,496,330 coronavirus infections, almost half those reported globally. In one 24-hour period in mid-May, 4,529 patients died of Covid-19.

Overwhelmed hospitals across the country have been unable to accommodate patients, more and more of whom need oxygen.

In the absence of good government, NGOs and volunteers, including students, have appealed on social media for medical supplies. But despite this crisis, universities seem to be living in a bubble.

Lockdown anxiety

Research has found that lockdowns and university closures owing to the pandemic are harming students’ mental health.

In one study, of 195 young people, 71 per cent displayed signs of anxiety or depression, or of being under undue stress.

“A lot of my relatives are getting Covid and I’m in a constant existential crisis about how I have the privilege to study when others are suffering,” said Sourish, a journalism student.

Undergraduate Nandini said: “I doom-scroll endlessly and then nap due to exhaustion, procrastinating on every important thing that needs to be done.”

When classes went online last year, students emptied hostels and moved back in with their families, so they lost access to vital resources such as libraries.

For some, cramped homes, borrowed phones, erratic internet coverage and domestic responsibilities placed strain on their mental health and affected their studies.

Intermittent lockdowns and surging rates of infection have created uncertainty about the future, and decision-making has been anything but swift, hindered by bureaucracy in central and state universities comprising dozens of colleges.

Students have had to petition for the suspension of classes and the extension of deadlines.

In such a scenario, the onus has been on teachers to be sensitive to students’ needs. Jyotsna Pathak, who lectures at a Delhi University college, often makes time during online classes for chatting with students to gauge a sense of their mood.

“If someone is not in a position to complete an assignment on time, I ask them to submit whatever is possible, and then re-submit a fresh one later.”

Some students do take advantage of this leniency, she said, but the percentage is low.

A helping hand

But one university – the National Law University in Delhi – ranked as the second-best law school in India, revised its approach to teaching after the second wave of Covid-19 hit the country in March.

The small institution, which has only 400 students, has “autonomous” status, allowing it the freedom to devise its own curriculum,

It declared that the final exam would include only 40 per cent of the syllabus instead of the usual 70 per cent – the rest would be tested as small chunks of home assignments.

Students received three weeks off in April and May, to reduce their screen time while they worked on assignments. Deadlines were extended for those struggling with ill-health.

The convener of the examination committee, Anju Tyagi, said that in contrast to bigger universities, there are fewer barriers in seeking permission for change, owing to the university’s autonomous status.

But what NLU Delhi is doing, Ms Tyagi said, is not rocket science.

“We’re constantly listening to the requirements of the student committee,” Ms Tyagi said. “We’re just being human.”