One August evening, a distraught woman was found by charity workers as she sat on the porch of her home waiting for her family to open the door.

Lakshmama, 64, had just returned from a month-long stay at a government-run hospital in southern Hyderabad city, where she was treated for severe health complications after contracting coronavirus.

But she had become a pariah for her only son and daughter-in-law, who despite her full recovery shunned Lakshmama in the belief that she still carried the virus.

"We had to convince her son to take her back. They were not ready to accept her and argued that she was a threat to them," said Mujtaba Hasan Askari, the founder at Helping Hand Foundation, which looked after Lakshmama for several weeks until she returned home.

Sadly, it is not an isolated case.

Thousands in India face a similar fate as a growing number of families abandon elderly relatives who have become victims of the stigma and misunderstanding surrounding the pandemic.

More than 9.4 million people in India have been infected by the virus that has killed nearly 138,000 in the country.

About 53 per cent of fatalities are people older than 60, according to health ministry data, making them the most vulnerable group.

Mr Askari's charity rescued at least 20 elderly people who were disowned by their children and relatives. Another 30 were rescued by Hyderabad Police.

Experts say it is not only the virus that is posing a challenge to the country's elderly population, but increased social, financial and emotional mistreatment.

From widespread discrimination in the treatment of older patients in overwhelmed hospitals, to the refusal of families to perform last rites for those who died of Covid-19, the pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of being elderly in India.

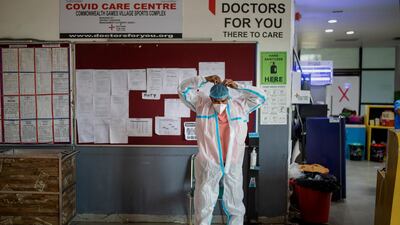

Staff at a government-run Covid-19 care centre in western Pune city are among those dealing with a spate of abandoned elderly people.

A 77-year-old patient was stranded at the hospital for more than a month after his son refused to take him home, claiming his father would not receive proper care.

Doctors said the son was dodged them for weeks.

"The fear of an increase in the caregiving burden due to dependency, and loss of livelihood due to the pandemic, has pushed the youth to such behaviour," said Dr Radha Murthy, managing trustee of Nightingales Medical Trust in Bangalore, a group that has rescued at least 18 elderly women since April.

She said families were worried other relatives would become infected, especially grandchildren.

India has more than 100 million people above the age of 60 and the number is expected to surpass 300 million in the next three decades, according to a government census from 2011.

But mistreatment of the elderly is a deep-rooted problem that predates coronavirus.

"We have been dealing with cases of abandonment and abuse for many years. The old people are subjected to not only physical abuse but neglect, verbal and financial abuse, like forcefully taking away their properties," Sonali Sharma, head of communications at HelpAge India told The National.

Decades of government efforts in disease eradication, poverty alleviation, sanitation and health awareness have led to an increase in India’s average life expectancy from 48 years in 1970 to 69 in 2020.

But the lack of a robust social security system and health initiatives remain the main challenge to increasing quality of life.

More than 70 per cent of the elderly in India are fully or partially dependent on their families for financial support, according to 2017 government figures, making many a burden on their children and relatives

In some cases that can lead to abuse.

India imposed one of the world’s strictest lockdowns from March until May, leaving tens of millions of people out of work and hampering their ability to feed their families, including elderly relatives.

The crisis triggered a sense of apathy towards older relatives, leaving some in desperate circumstances.

"The condition of old-age people is disturbing. Children are abandoning their parents as they migrate to other cities to earn a living," said Shiv Pratap, a field co-ordinator with Agewell Foundation, a group in Delhi that distributes protective equipment and food to 400 elderly people in city slums every week.

“These old-age people have neither money nor means to stay safe during the pandemic."

The problem was further exacerbated by a government measure that banned over-65s from travelling for non-essential work, making them rely on their families for the smallest requirements, including grocery shopping.

The restrictions meant many were disconnected from society, triggering heightened feelings of loneliness, anxiety and depression in some cases.

A study by HelpAge India showed that the elderly were the group worst affected by the pandemic.

Of the 5,000 people aged over 60 featured in the survey, 65 per cent said their livelihood was affected by the pandemic.

A similar amount suffered from chronic ailments including asthma, hypertension and diabetes, making them highly vulnerable to financial and health risks.

“When Covid happened everything came to a standstill for them,” Ms Sharma said.

“For those whose children were migrant labourers, their money stopped during the lockdown and at the end of the day, the elderly got affected most because they have food and medical needs."