It was a chilly Friday afternoon when an extended roar of more than two dozen motorbikes pierced the silence in the Spin Boldak district of Kandahar province.

To an outsider, the sudden invasion earlier this month by a large group of men on bikes could be cause for alarm, but for the residents of the small southern villages in the historical region of Afghanistan it was a welcome sound.

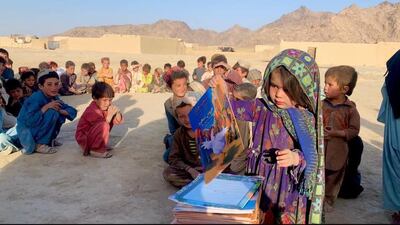

Children flocked to the streets and excitedly chased the bikes. The men – activists with an Afghan NGO called Pen Path – were known to the children as “brothers who bring them books”.

On this day, however, the convoy was also carrying placards with messages promoting girls' education in Afghanistan, an issue that has been of growing concern since the Taliban seized control of the country on August 15.

The insurgent group, known for its extremist views particularly related to women’s freedom, has failed to reopen the majority of high schools for girls in the country.

“After Taliban suspended grade 7 to 12 education for girls, we started this campaign, involving scholars, educators, men and women, to request the Taliban to restart girls school. We want to emphasise that education is our Islamic and basic right,” said Matiullah Wesa, the Afghan education activist behind Pen Path.

Mr Wesa, who started Pen Path 12 years ago because many districts near his hometown in Spin Boldak were without school facilities, said he hasn’t heard back from the Taliban, but remains hopeful.

“We will continue this campaign because this is one issue we can’t remain silent on; girls’ education is our red line,” he said.

Even as other groups, including the Taliban, struggled to come to terms with the new reality in the aftermath of events in August, Pen Path resumed operations within 48 hours of the fall of the Kabul government.

Unwilling to allow schools in Afghanistan to become a casualty of the developing crisis, Mr Wesa and a group of volunteers hopped on their bikes driving from village to village, urging elders and locals to restart their schools and public libraries.

Their teams headed first to south eastern Kunar province where they met tribal elders, religious scholars, teachers, and residents, and urged them to open dialogue with local Taliban members to keep schools and universities running.

Since August, Pen Path teams have campaigned in 42 districts across 13 Afghan provinces.

“The Taliban takeover dramatically impacted our work, particularly for women who were part of the door-to-door campaigns,” said Zarlasht Wali, a Pen Path board member.

“We used to travel to provinces and districts with our campaigns, but now due to the threats that we face we can’t move around. But now, if the Taliban even get a whiff of a campaign, they forbid it.”

“There was this village with 1,200 families and hundreds of children, but no schools were built there for decades since the war never stopped. It broke my heart to see my people deprived,” he said.

Promoting girls' education

Over the past decade, Pen Path has re-opened more than 100 schools, registered 46 new schools, and started 39 public libraries.

“Our primary focus is on creating awareness about education and particularly girls education. Apart from that we help communities open schools with the help of government or NGOs, and also provide martial support where needed,” Ms Wali said.

Pen Path is funded by local donations and operated entirely by volunteers. "We don't have any funds from governments or international NGOs. We are supported by the people," Mr Wesa added, with pride.

Mr Wesa and his 2,400 volunteers across the country are no strangers to threats and violence.

“For years now, I have been driving my motorbike across Afghanistan, with bombs and explosions in the backdrop, campaigning to restart closed schools, help locals register new schools, and encourage girls' education,” he said, sharing stories of close calls they’ve had.

“But we are from the people, the people support and protect us. We are not associated with any political group and all we want is to ensure every Afghan child has access to education.”

Education sector collapse

As the crisis in Afghanistan deepens, the work and experience of organisations like Pen Path have become increasingly crucial. Afghanistan’s education sector has taken a severe hit since the Taliban takeover.

As the country reels from a financial crisis, many teachers are finding themselves unemployed and even starving as institutes fail to pay salaries.

“Teachers have lost their jobs. This is despite the Taliban promising that teachers and healthcare workers would be allowed to work. Private and public schools have both downsized. I know a teacher who is now polishing shoes on the streets because she has not been paid,” Ms Wali said.

On the other hand, there has been an increase in dropout rates, she pointed out. “Most parents don't want to send their children to school because of security, or can’t afford to because of the financial crisis. By security, I don’t mean an absence of explosions...but a lack of trust between the nation and the government,” she said.

“Everyone I talk to, parents, teachers or students, they are all depressed. The little progress we had seen over the years has been reversed,” she added.

Over the years, Pen Path has been operating “home schools”, often discreetly and unknown to the authorities, in districts where regular schools were absent or forbidden by the Taliban.

“Since the Taliban takeover, we first restarted our home schools which are run by women volunteer teachers with 15-16 girls in each class. We provide the teachers with a small salary and materials like books, and our volunteers regularly visit these schools to monitor the quality,” Ms Wali said.

Pen Path also has online classes for those with an internet connection and provides pre-recorded video lectures to students stuck at home.

“If nothing else, we at least try to provide them with story books delivered through our mobile libraries on motorbikes. We tell them that even if there is no school, study at home by yourself,” Mr Wesa added.

Ms Wali had hoped, over the years, that the need for such secret schools would reduce as the conflict abated.

However, Pen Path has had to expand the programme in recent months, she said.

“This was our worst case solution that we implemented during war. Now, with the conflict over, we should have regular schools and not have to rely on these home classes,” she said.

Along with other members of Pen Path she remains determined to continue their work, despite threats.

“What I am doing is what Allah would have wanted us to do. As a believer, it is part of our faith to encourage education. Even the first word of the Quran is ‘read’—that shows the value of education in our religion,” she explained, adding that if girls’ education is not resumed, “we will be killing at least half of the generation,” she said.

Mr Wesa strongly agrees.

“We use our motorbikes to spread the message of peace, which is incomplete without women’s rights. I often receive threats, and I always reply, I want to rebuild the country again, but it is not possible to do that without ensuring women’s fundamental rights, from Bamiyan to Kandahar, from Helmand to Badakhshan. And I am ready to die for this,” he said.