It is past midnight in Kabul, but the phones of 180 Afghan women ping as messages arrive and screens light up with the persistent chatter of resistance against Taliban rule.

Few on the WhatsApp group share their real names, and fewer still have a profile photo. But all are Afghan women, trusted with an invitation by a core group to plan a revolution.

“We will continue to raise our voice. The world will listen,” one woman wrote.

“Ufff, when will the morning come so we can go out [to protest] again?” another asked.

The group's name – changed often to avoid detection should any of the women be detained – is anonymous, as are the women who run it. But the theme revolves around a rough translation to “women’s justice”.

It is one of many groups of largely Afghan women, some as young as 15, who are mobilising others to protest against the Taliban’s oppressive regime.

The Taliban swept into Kabul on August 15, taking their strict ideology with them – one they used to frighten and oppress women when they controlled Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001.

“We have been abandoned. Everyone around the world is watching the atrocities the Taliban are committing against us, but not one country or international organisation is doing anything about it. It’s up to us to defend our rights,” said Zahra, one of the women leading protests in Kabul, adding that Afghan women feel betrayed by their allies.

“They held a number of conferences, invited the Taliban for talks around the world, signed a deal with them on the promise that they will protect our rights. We repeatedly said we didn’t trust them, but no one listed to us,” she said.

Zahra is a medical professional who has been unable to work in her clinic since the Taliban took over. Although the Taliban asked medical workers, including women, to return to work, Zahra said there was widespread harassment of women.

women's rights activist

“The five kilometre journey from my home to my workplace is full of threats, risks and humiliation. I have been stopped numerous times by armed fighters. I get questioned, my phone is checked. It is extremely frustrating,” she said.

The Taliban have imposed strict limits to women’s participation in social and political spheres. Their Cabinet does not include a woman, and the group’s position on the future of women working is vague.

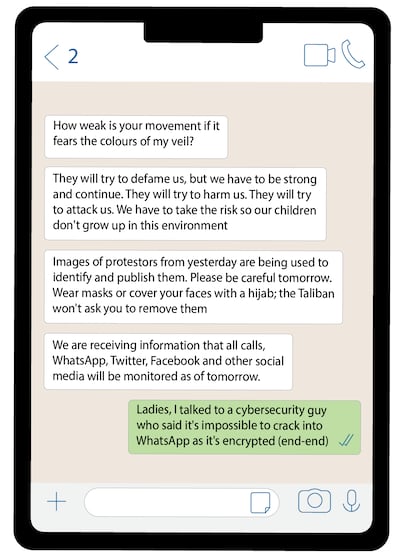

The Taliban have also reportedly used encrypted messaging service WhatsApp to communicate, despite being banned by Facebook, its parent company.

“We are not asking for anything more than our rights as prescribed in Islam. We are Muslim women and we know what rights have been given to us,” Zahra said.

But the demands made by the women leading the protests, which have occurred in cities across Afghanistan since the Taliban seized power, are not just about their rights.

The movement is deeply intersectional, demanding media freedoms, tolerance of ethnic and religious minorities, and gender balance in social, political and public spheres.

“We are talking about the attacks on media. We have also raised voices against the Taliban’s violence in Panjshir, their blockade of crucial humanitarian aid to the province, and Pakistan’s interference in internal Afghan affairs,” said Sara, a high school pupil and a protest organiser.

Prevented from working and going to school, women like Sara and Zahra are directing their energy towards mobilising other women and youths to joining their peace protest to demand a review of how the Taliban rules Afghanistan.

Zahra, who had participated in many protests, organised her first demonstration days after the US and Nato allies' withdrawal was complete.

“I was leading the group, chanting slogans demanding our rights. We got very close to the fighters and they started to yell at us. One of them told me ‘Don’t come any close or I will shoot’, but I kept moving forward slowly and tried to talk to him.

“He was pointing his gun at me, but I felt strong in the company of other women, so we kept moving forward and crossed the checkpoint,” she said.

Since the first protest, Zahra has organised many others, each one better planned than before, having learnt from the experience.

“We have a social media group, where we only add women we trust. Before we go out, we plan everything and discuss every details well in advance, from security to crimes and other problems,” she said.

Every demonstration is planned a day or so before, an agenda is set, routes are finalised, and security issues discussed.

“We also take measures for safety, like using various social media platforms that cannot be traced, with generic group names, and also regularly deleting older messages, photos and videos that can be incriminating if found,” Sara said.

The women also insist that all members must keep protests civil and peaceful.

“We urge protesters to stay calm, and don’t engage in violence. We have been pretty clear with our team that if any of them chose the path of violence, they are not with us,” Zahra said.

“Because if we were seen as violent, the Taliban would grab the opportunity to beat us and shut us down. We are not here to protest for a day, make headlines and leave. We want to continue this, for generations if necessary,” she said.

With a long-term commitment such as theirs, the women realise that the importance of keeping morale high. Most conversations on the groups are women providing emotional support.

“We are all scared. Many of us cry, but we have to do this and we are each other’s allies,” Zahra said.

When one of the women in the online group said she was crying and feeling scared and hopeless, Zahra told her: “You don’t die everyday; death only comes once and I would rather die fighting with pride than being humiliated.”

In another social media group, Sara echoed similar sentiments to her group.

“We lost thousands of lives to reach here and achieve all what we have, so how can we keep silent now?”