As cash flows in to assist African nations with the coronavirus pandemic, one group of volunteers is tracking the spend

In early April, the northwestern Nigerian state of Kaduna set aside $1.3 million to purchase food packages for vulnerable households amid restrictions on movement due to rising cases of the novel coronavirus in Nigeria.

As distribution began across local councils, Zaliha Lawal and a group of over 20 volunteers monitored it closely, taking photos and video and recording instances where officials diverted the items or allowed unfair distribution patterns to favour their friends or relatives.

“We felt it was very necessary to make sure the food items reach the real beneficiaries,” the 31-year-old transparency and accountability campaigner said.

Where irregularities arose, the team submits a report to state officials who, for the most part, promise to address the issues at stake.

Ms Zaliha and the volunteers are part of Follow The Money (FTM), a movement of anti-corruption campaigners tracking and visualising public spending on health, education and other development projects in mainly rural communities to improve transparency and accountability.

Launched in 2012, FTM is an initiative of Connected Development, a Nigerian nonprofit working with local communities to fight for efficient use of public resources. Members, known as champions, include activists, lawyers, development consultants, researchers, and data analysts, all of whom are signed up on the movement’s social mobility platform.

As cases of Covid-19 continue to rise across Africa, international aid and loans are pouring in.

The International Monetary Fund promised $11.5 billion in support for 32 African nations and the World Bank has pledged $50 million to Kenya, $7.5 million for Liberia, $37 million for Malawi, and $10 million for The Gambia.

The amounts are staggering, but details on how exactly the funds will be spent are patchy, sparking fears the cash will be funnelled into pockets of those in power.

Government statements provide only cursory descriptions of funds being allocated to areas including medical supplies, surveillance and response, capacity building, quarantine and isolate centres. There is little accountability for how the money is distributed on the ground.

FTM’s Covid-19 Transparency and Accountability Project is engaging its network of over 6,000 members in Nigeria, Liberia, Cameroon, The Gambia, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Malawi to track all funds.

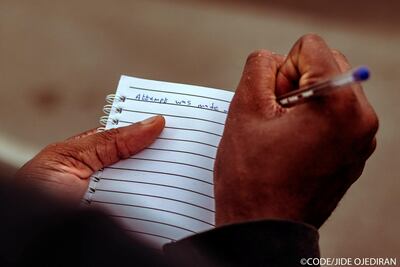

Members are mapping, documenting and monitoring donations, loans, procurement processes, food packages as well as cash transfer programmes and amplifying their voices for shared change using the hashtag #FollowCOVID19Money.

Collectively, they are challenging public officials to always use open contracting standards so that all contracts can be scrutinised, said Hamzat Lawal, founder of FTM and CEO of Connected Development.

Methods of tracking the disbursement of funds vary from country to country, but include filing freedom of information requests, watching and recoding the handover of goods in person and pressuring governments to release reports on spending.

In Nigeria, the team is using an open-source spreadsheet to track all donations to federal authorities as well as across the country’s 36 states. In The Gambia, FTM champions are visiting isolation centres to ensure monies meant for testing kits and other equipment are resourcefully used.

In Zimbabwe, plans are under way to organise a virtual hackathon where young people will visualise all data about funding and food packages into apps, widgets, and WhatsApp pods to make these details accessible to different communities.

For Teslima Jallow, an anti-corruption campaigner in The Gambia, joining FTM was mainly driven by a burning desire to advocate for social justice and hold politicians accountable.

Corrupt public officials will easily divert Covid-19 funds if they are not monitored closely, Mr Jallow warns, “and when this happens again, we will be the very people who will be left to suffer.”

At the heart of FTM’s strategy is collaboration, both with other NGOs and government agencies, says Eve Mathai, FTM’s country director for Kenya.

“No matter how much advocacy you carry out, those efforts are very futile if you don’t engage on a policy level.”

Nowhere is this collaboration more pronounced than Libera. FTM members there are working with other partners such as the Liberia Youth Wash Coalition, the Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission, and General Auditing Commission of Liberia to share reports on funds raised, how they are expended and to call for investigations where necessary.

Similar investigations have been carried out in Gambia. In late April, the Gambian finance ministry claimed that 160 million Dalasi ($3.1 million) out of a 512 million Dalasi (around $10 million) Covid-19 Emergency Response Fund was expended largely on providing medical equipment and supplies, training health workers, refurbishing health facilities, purchasing ambulances and pick-up trucks for front-line workers, and providing hotel accommodation for quarantined individuals.

After a month-long inquiry, FTM campaigners discovered that 45 per cent was spent on hotel bills and 40 per cent on purchasing eight Nissan pickups rather than equipping and renovating health facilities.

Health workers who spoke to FTM members found fault with the ministry’s claims and complained about a lack of training and protective equipment as well as unequipped isolation centres and insufficient hygiene items.

Similarly, the activists found that fraudulent names were deliberately included in a list prepared to pay risk allowance to frontline workers. Mr Jallow said they compared expenditure reports from the ministries of health and finance and uncovered discrepancies amounting to 1.073 million Dalasi or $20,885.

"We have written to the National Assembly to take action and asked that an investigation committee be instituted to look into this and bring the perpetrators to book," he told The National. The majority leader of the National Assembly has acknowledged their letter and promised to look into their findings, he added.

One central tenet of FTM’s work is ensuring accessibility to the data they are collecting. This means making messages available in local languages, including Swahili and Sheng in Kenya, Hausa in northern Nigeria, and Mandinka in The Gambia, and many more, Ms Lawal hopes the pressure from all these intensive anti-corruption efforts will keep public officials on their toes.

“Our work is not only to criticise always; we often proffer solutions through our reports to avoid a [recurrence] in the future,” she said.