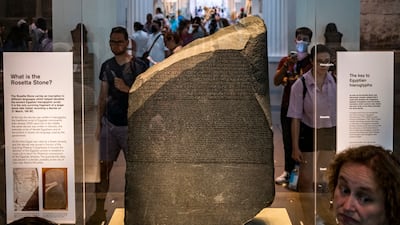

What is the Rosetta Stone?

A priceless stone tablet from Ancient Egypt, dating back to about 200 BC and rediscovered in 1799, that taught the modern world to read hieroglyphics from more than two millennia ago.

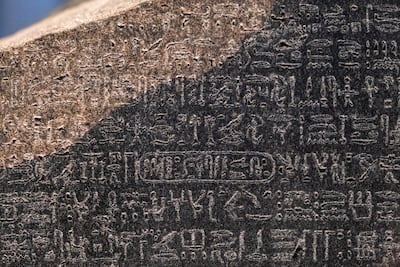

Inscribed on the Stone, 112cm high and made of a granite-like rock, is the same message in three different languages – formal hieroglyphics, an everyday Egyptian script and Ancient Greek.

After its discovery, scholars used their knowledge of Ancient Greek to decode the hieroglyphics and the Stone became one of Egypt’s most famous relics.

How was it discovered?

Accidentally, by French soldiers during the Napoleonic Wars.

Fighting in Egypt, some of Napoleon’s forces came across the Stone while digging the foundations of a fort near the town of Rashid, also called Rosetta.

Pierre-Francois Bouchard, the officer in charge, went down in history as the Stone’s discoverer after realising the significance of his find and passing it to scholars.

But the Stone did not remain in French hands, as Napoleon’s war loot was handed to Britain in the 1801 Treaty of Alexandria, and it was subsequently shipped to England.

Where is it now?

The British Museum in London, which has had the Stone in its collection since it was presented by King George III in 1802. It is housed in a glass case in the museum’s Egyptian Sculpture Gallery.

The only time it is known to have left the museum was in 1917, during the First World War, when it was moved to an underground railway tunnel to keep it safe from wartime bombing.

What is written on the Stone?

The actual text is not of enormous significance. It is a decree by a council of priests that venerates a young king, Ptolemy V, on the first anniversary of his coronation.

The Rosetta Stone is only a broken fragment of a larger whole and it is thought that the same message would have been reproduced on other tablets.

But the Stone contained enough clues for French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion to crack the code, although it was not until 1822 that he announced his findings in Paris.

His breakthrough pushed open many more doors as scholars started deciphering letters, documents and works of poetry from Ancient Egypt that had previously been illegible.

What are the languages on it?

Hieroglyphics: the pictorial script most commonly associated with Ancient Egypt, although by 200 BC it was already archaic and only used in formal settings such as this. It had fallen into complete disuse by about 400 AD and later scholars could not read it until the Stone’s discovery in 1799.

Demotic script: the everyday script used by literate Egyptians at the time the Rosetta Stone was inscribed. Like hieroglyphics, it fell out of use and was gradually pieced together again with the help of the Stone.

Ancient Greek: used by the rulers of Egypt at the time following its conquest by Alexander the Great. Still understood by some scholars in 1799, it was the key that allowed them to decipher the Egyptian languages.

What will happen to it next?

The British Museum is staging an exhibition to mark 200 years since Champollion’s breakthrough in 1822, titled 'Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt'.

The Rosetta Stone will be part of the display, which was described by a museum spokeswoman as a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for visitors to learn more about the Rosetta Stone’s significance and legacy”.

But some people, notably including Egyptian archaeologist and former antiquities minister Dr Zahi Hawass, believe the Stone was stolen and rightfully belongs in Egypt.

Dr Hawass plans to petition the British Museum this autumn to return the Stone, while making similar appeals to French and German collections to hand over other treasured artefacts.

The museum said no formal request to return the Stone had ever been received.