On a sunny July afternoon, Reena Verma walked through the winding lanes of Prem Gali Muhalla in Pakistan’s Rawalpindi as thrilled locals showered flowers, played drums and sang music in her honour.

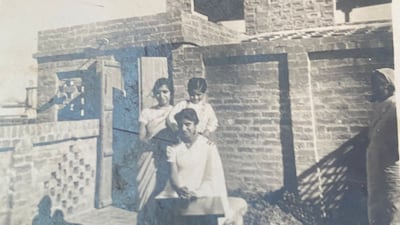

The grandmother, 92, a small figure with a white bob haircut, looked in awe and disbelief as she reached the three-storey house where she was born and lived with her parents and five siblings until the Indian subcontinent was divided at the end of British rule in 1947.

She visited each room and relived the memories of her upbringing in the house. She also spent a night in the room that was once hers.

It was the first time in 75 years that Ms Verma had stepped into the family home — now owned by a Pakistani Muslim in what became the Pakistani province of Punjab.

“It was a very emotional moment for me. I went to each room, even on the first floor and second floor. I could see my family roaming around. I could see the things that were kept on the mantlepiece,” Ms Verma told The National.

“I had mixed feelings because I was both happy and sad simultaneously. All of us had lived there together but I was there alone. We lived very well, all of us were fond of music and had gramophones and radios.”

Ms Verma was 15 years old and was on holiday in the Solan Valley in the Himalayas — currently part of India — at the end of colonial rule, a moment that marked the start of a tumultuous and bloody partition leading tens of millions to migrate on sectarian lines.

Her father, a British government employee, had arranged a regular holiday for Ms Verma and her three sisters in May. But this time they went to the Himalayan mountains as the situation was tense in their home state of Punjab, home to Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims.

She had packed some books, woollen clothes, marbles and dolls, and bid goodbye to her home with the hope to return in a few months.

But three months later in August when the British left and the subcontinent was divided into dominions of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan, Ms Verma became a refugee.

In the chaos, fear and shock, Ms Verma and her sisters remained in newly born India.

Her books, clothes and dolls were her only possessions.

As sectarian riots raged in the region, millions of people were uprooted and mass migration ensued, with families leaving everything behind.

More than a million people are estimated to have died in the following months as trains filled with bodies arrived across the Radcliffe Line — their passengers massacred by fanatical mobs as they tried to cross the new border between the Indian and Pakistani portions of Punjab Province.

Ms Verma’s family fled their home to migrate to India where they reunited and settled with their daughters in a Himalayan town that is now part of India’s northern Himachal Pradesh. They then moved to Pune in western Maharashtra where her brother, who was in the army, had relocated.

“We never thought we were not coming back,” said Ms Verma. “There were uncertainties, but we thought we would come back. My mother was in disbelief that she couldn't go back even two years after the partition.

“We had nowhere to go as my father had already returned and his pension was very less. Whatever money we had, we had put in three banks and all three banks failed.”

Over the years, Ms Verma built a fulfilling life in India.

She completed her education, worked at the government's cottage industry department, got married, had children and grandchildren.

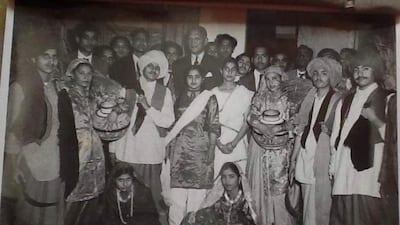

She participated in beauty contests and dance competitions and sang to her heart’s content.

But deep down, she yearned to see her ancestral home, at least once.

The relationship between India and Pakistan has remained frosty and the nuclear-armed rivals have fought three wars since independence.

“Life was very peaceful and happy and since we were children, it was a normal life. We used to go out for movies and travel to Lahore and other tourist places,” she said.

Visiting the rival nations remains a challenge for many like Ms Verma, as getting visas is difficult owing to political hostilities and deep-rooted suspicion between the two governments.

Ms Verma’s visa was rejected at first, but her dream finally came true in July with the help of Pakistan-based activists and journalists.

It happened after she joined an Indian-Pakistani heritage group on Facebook and wrote of her desire to visit her old home.

Ms Verma said her visit also highlighted the love and connection between the people of two countries that are sparring because of politics.

She urged their leaders to resolve their disputes and open their borders so that their citizens could meet each other.

“It has been decades and it is useless talking about the partition and the wrongdoings. The younger generation was not part of it,” she said.

“I am a survivor of partition and yet I am saying that both the governments must forget about the partition and make it easy for the young generation to meet and make future relations better.”