President Joe Biden is using America's defeat in Afghanistan to accelerate his approach to US foreign policy that breaks from the kinds of expensive and drawn-out military interventions that have defined the global security order since the end of the Second World War.

With the Taliban back in power after 20 years and unresolved conflicts simmering across the Middle East, the US has not managed a clear-cut military success since the 1991 Gulf War, when it recaptured Kuwait from Iraq's Saddam Hussein.

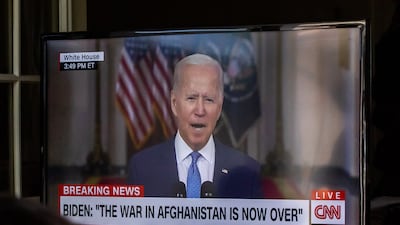

During a speech defending his handling of America’s messy withdrawal from Kabul, Mr Biden said his decision to end the war was also about “ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries".

“We must set missions with clear, achievable goals — not ones we’ll never reach,” he said.

It's a turnaround for Mr Biden.

First as a senator, then as vice president, he repeatedly voted for foreign military interventions, from Yugoslavia in 1999 to Libya in 2011, as well as the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

“As we turn the page on the foreign policy that's guided our nation the last two decades, we've got to learn from our mistakes,” he said, noting that future military interventions must be focused mainly on the “fundamental national security interest of the US”.

But a reduced role for America as the world’s policeman worries allies in the Middle East and Europe.

“It sounds like the end of an era,” said Bruno Macaes, a prominent European author on geopolitics and a Portuguese politician.

In his speech, Mr Biden said human rights would be at the centre of US foreign policy, but noted these would not be enforced through “endless military deployments”.

Instead, the US would use “diplomacy, economic tools and rallying the rest of the world for support,” he said.

Mr Biden has sought to reassure allies that “America is back” after four years of Donald Trump’s isolationist “America First” worldview and verbal attacks on partners, including those in Nato.

But several allies, including Britain, France and Germany, are unhappy with America’s end to the Afghanistan war, which came with little co-ordination even though hundreds of troops from those countries had been killed in the two-decade conflict.

“Mr Biden wants to appeal to a strong notion of the American national interest. That has a cost: partners can no longer expect their own interests to be taken into account in major US foreign policy decisions,” Mr Macaes said.

Gerard Araud, the former French ambassador to Washington, put it more bluntly on Twitter.

“Wake up, Europe! Your nanny has resigned,” he wrote after Mr Biden’s speech.

Gen Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, sounded a chastened tone at a Pentagon press conference on Wednesday. For years, military officials assured the American public that the Afghanistan conflict could be won — until suddenly it couldn't.

“Our military mission has now come to an end. We will learn from this experience as a military, and how we got to this moment in Afghanistan will be analysed and studied for years to come,” Gen Milley said.

“We in the military will approach this with humility, transparency and candour.”

Richard Haass, a former US special envoy to Northern Ireland and a seasoned diplomat at the heart of the Washington foreign policy establishment, hit back at Mr Biden's decision to retreat from Afghanistan, but agreed the US should not be looking to nation build.

“Transformation of other societies is not a realistic goal for US foreign policy or good use of the US military. But building up local capacities to tackle terrorism and promote domestic order is a proper foreign policy goal, one in our national security interest,” he said on Twitter.

Mr Biden said America must refocus its foreign policy to counter challenges from Moscow and Beijing.

“There’s nothing China or Russia would rather have, would want more in this competition than the United States to be bogged down another decade in Afghanistan,” he said.

But this approach could grow complicated, as many US allies are hesitant to anger Beijing.

“We are hearing from EU officials that a new caution is necessary on forging a common EU-US policy on China. That’s an immediate and heavy cost of the Biden decision,” said Mr Macaes, author of Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order.

He stressed, however, that European and Asian allies remain dependent on Washington for security — at least for now.

In the Middle East, fears of a similar US withdrawal from Iraq and a more isolationist American policy are forcing regional players to reconfigure their own relations and security.

Over the past two weeks, reconciliation efforts have gained momentum between the UAE and Egypt, and between Turkey and Qatar.

Saudi Deputy Defence Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman visited Russia last week and signed a military agreement.

Karen Young, director of the Economics and Energy Programme at the Middle East Institute, saw these developments as ways for countries to manage their own disputes while the US shrinks its footprint in the region.

“It is all related [to Afghanistan], but also anticipated before the US withdrawal, where there has been a need for Gulf states to de-escalate tension and some active disputes, to create some opportunities for economic co-operation,” Ms Young told The National.

“Without a US commitment to force in the region, there have to be other ways of dispute management.”

Whether it’s Turkey and the UAE mending ties, or Iranian-Saudi backchannel talks, the expert saw it linked to “a more opaque regional security environment, more pressing economic needs and [that] requires some deal-making".