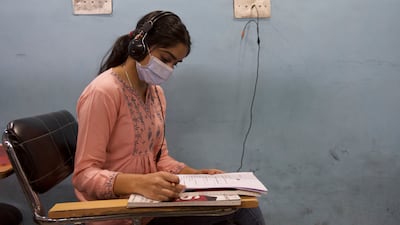

Ranjit Kaur is carefully following her English teacher in the classroom. Her eyes are glued to the white board where he breaks down a sentence into nouns, pronouns, adjectives and explains tenses.

There are half a dozen female students in the classroom – all aspiring to emigrate.

It is one of several English coaching centres in Jalandhar in India’s northern state of Punjab, where women are taking English language lessons for a mandatory test required to migrate to an English-speaking country, such as the US, the UK or Canada.

“I am preparing to go and study abroad but I am not good at English. This coaching is helping me to hone my skills. I am improving my grammar,” Ms Kaur told The National.

Ms Kaur is among tens of thousands of youngsters in the state who dream of moving abroad in search of greener pastures.

Punjab is one of the most prosperous states in the country. An agrarian belt, it is the breadbasket of the country and provides rice and wheat for the entire nation.

Most of the population is educated and live in good conditions.

But every family, whether rich or poor, from rural or urban areas, has at least one member who lives abroad or aspires to do so.

Every year, thousands of people from the state move to countries such as the UK, US, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada but also to other European countries and to the Middle East, including the UAE, in search of financial prosperity and better living standards.

“It is like a woman’s love for gold. Like gold never stops luring a woman, foreign destinations have the same effect on Punjabis,” Arvindar Pal Singh, who runs an immigration consultancy and travel agency in Jalandhar city in Punjab, told The National.

Greener pastures

Indians have the highest diaspora population in the world, with 18 million living abroad, the UN says. More people continue to leave the country in search of new opportunities.

This year, by June more than 87,000 Indians had given up their citizenship after obtaining foreign nationalities – India's laws prohibit dual citizenship.

More than 470,000 people from the state left the country for work and more than 260,000 people to study between 2016 and 2021, the foreign ministry said.

Moving abroad is a status symbol for many families in the state. It is common to see houses flying flags of the UK, Australia or Canada, a sign that a family member lives abroad.

Being a Non-Resident Indian is often equated with better financial prospects.

“I don’t feel we have good opportunities here or good salaries. I want to experience new things, and study in advanced universities. My brother is in Canada. He makes more money and has a better life. I want to experience that life,” Ms Kaur said.

The wave of emigration began in the late 1960s when people from rural and agricultural families moved abroad in search of work.

They would often come back to take one or two relatives with them.

Reasons for wanting to live abroad vary for families and range from seeking better opportunities to escaping the drug menace.

The north Indian state of 30 million people on the border with Pakistan has for decades been plagued by drug abuse.

“For parents, it is the best investment to send their young children abroad for higher studies, but also to keep them away from drugs,” Mr Singh said.

Consecutive governments have struggled to address the issue and have made promises to eradicate it but there are as many as 700,000 drug users in the state, according to official records.

The state is divided into rural and urban classes with rural families working mainly in farming, something the younger generations are often not interested in pursuing, Mr Singh said.

For the urban class, the source of income is either business or jobs. However, competition and limited opportunities mean unemployment is rife.

Punjab’s unemployment rate was 8.2 per cent in February this year, higher than the average national unemployment rate of 7.5 per cent, said the Centre for Monitoring of Indian Economy, a think tank.

“There is disguised unemployment. Most families have farms here and all members are engaged in it, but not every person is really working. There is enough time in hand and the state has a problem with drugs,” Mr Singh said.

The lack of work opportunities has pushed young Indians to persue employment opportunities overseas.

Some families prefer English-speaking destinations such as Canada, which offers about 300,000 visas to Indians every year, mostly students of whom 60 per cent are from the state.

Students are from science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine backgrounds.

Others apply for entry-level and midlevel positions in retail, business services, and manufacturing sectors while some choose Italy, Portugal, or Spain where they can work on farms as labourers.

“They go for studies but with a mindset of settling there, for prosperity, for a better lifestyle. Here social security is missing from our society. There, they find financial independence, earn money, and help their families back home,” Mr Singh said.

Coaching and consultancy

Moving to a new country is not an easy process. It requires money and preparation, such as passing mandatory English language tests, and a lot of paperwork.

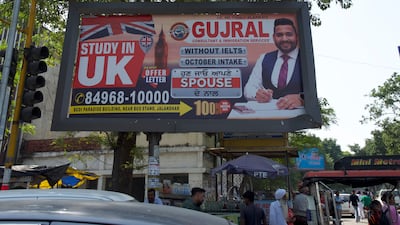

The demand has led to growing opportunities for businesses such as consultancy firms that have increased across Punjab.

In cities like Jalandhar, consultancy firms fill entire streets with flags of the UK, US, and Canada. They help people like Ms Kaur to secure places in universities, take them through the visa process, and even uncover job opportunities.

The service costs about 100,000 rupees ($1,200).

“They have to go through certain coaching because they have to prove they have enough knowledge of English for the desired course. They require a certain level of scoring for good universities. We provide them English classes and facilitate them with enrolment to university or for jobs,” Amarjeet Singh, managing director, Broadway, told The National.

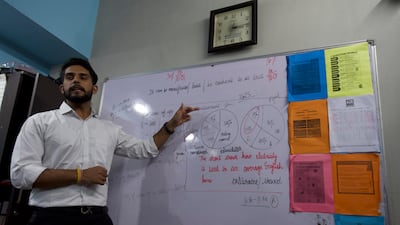

Akhil Katyal, who teaches English at Broadway, is also an aspiring emigrant. He has applied for jobs in Canada.

“Most of my friends are living abroad. They make better money, have less stress and live happily. They inspire me. I feel that life is better abroad because there are more opportunities to grow and respect for work,” he said.