Keith Richards once described music as being similar to air. While the Rolling Stones guitarist meant it as a figurative statement of devotion to his chosen art form, one of the great inventors of modern times has taken this literally.

Last month, the UK company Dyson, founded by British engineer Sir James Dyson, announced its entry in the headphones market. The Dyson Zone, which will be released this year, is described as a set of noise-cancelling over-ear headphones that deliver high-fidelity sound, while simultaneously pumping purified air into your nose and mouth.

If this sounds like something out of a sci-fi film, then you wouldn't be far off. The National experienced those futuristic vibes when the product was exclusively displayed at the Palais De Tokyo in Paris on Monday. Although we were able only to gawk at the products, not wear them.

They look hefty, but staff assure us that's because they're designed to distribute the load "over the sides of the head", in a method similar to a horse saddle.

The cushions look flatter and angled in line with the contours of the ear for extra comfort, while the noise cancellation feature is also touted as being able to reduce volume by up to 40 decibels.

These elements discerning audiophiles will undoubtedly investigate next year, but they may pause when encountering the key feature: a non-contact visor that pumps clean air to the nose and mouth courtesy of compressors built into each ear cup.

This exists simply so customers can breathe cleaner air, Dyson says. We ask him if it's in response to the pandemic, but he says development began years before Covid-19 entered our lives.

The overall look of the product — the colour scheme of the displayed product is blue and copper — resembles something straight out of a cyberpunk comic.

And while the official price tag has yet to be revealed, it will follow most Dyson products at being at the top end of the scale.

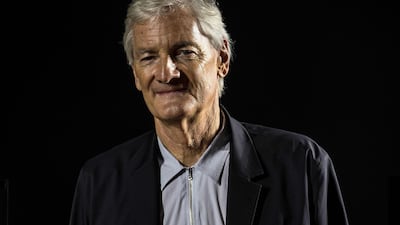

And that’s nothing to apologise for, Dyson says during a career retrospective called A Life After Art School. The value reflects the six years of development and 500 prototypes it's taken to come up with the final product.

He says it's the price of "being innovative", particularly because there are "huge" upfront costs. "Inevitably, it’s going to be expensive."

The hits and misses

The technology for the Dyson Zone was initially developed for Dyson’s failed electric car venture, which had reportedly lost more than half a billion dollars before the plug was pulled in 2019.

Where such an eye-watering amount could have curbed his ambitions, Dyson, 75, and his team powered on.

The road to his estimated $7.7 billion fortune has long featured prolonged setbacks and mastering the art of making disparate connections.

It all started in 1978 when his own vacuum cleaner was not doing what it was supposed to do. Taking a cue from the industrial cyclone tower he designed for his UK factory — one where a centrifugal force was created to separate paint particles from the air — the fledgling engineer applied the same principle in creating the world's first bagless vacuum cleaner.

He says the five-year research and development process nearly made him broke, with 5,127 prototypes created until he hit pay dirt.

The technology was sold to a Japanese company, after a series of “all night meetings”, which went on to brand it The G Force.

"It was named by a magazine as one of the designs of the decade, next to the Sex Pistols and the Pompidou Centre," Dyson says wryly. "After that I did my own licensing and technology and released my first vacuum cleaner, the DC1, in 1993.”

While Dyson vacuum cleaners have become a household name, there are plenty of products that haven't been quite as successful.

Consigned to the scrap heap in 2000 was a short-lived robotic vacuum cleaner. "It had 120 sensors and it had about 18 battery cells," Dyson says. "I realised that no one would buy it because it was too expensive."

The experience did trigger some soul searching, however, into the effective role robotics could play in our everyday life.

"I realised the future of robotics is vision systems. It is about being able to see, film and interpret what it is seeing."

This sowed the seeds for the Dyson 360 Heurist, a more refined take on the original robot vacuum cleaner that, through artificial intelligence, knows the contours of your home and cleans up on instruction.

Improving 'prosaic, boring and even nasty products'

Dyson has since become known for items other than vacuum cleaners, from cord-free hair straighteners to high-velocity fans, but Dyson is aware his sprawling empire has been built on the back of products that perhaps won't get people's blood pumping.

“I have never been attracted to glamorous products. I like the more prosaic, boring and even nasty products, like vacuum cleaners, and try to make them interesting and beautiful,” he says.

“I am sort of perverse in that way. I like taking on things that are not attractive and making them work better.”

It is a philosophy Dyson wants to leave as his legacy.

This is encapsulated in his 2021 memoir, Invention: A Life, in which he comes across as more fond of his failures than successes.

The biggest career setback, he says, came early on, when he was a minority shareholder in a company, leaving him creatively bereft. It's why he decided to launch Dyson and keep it as a family business.

It's also partly why he backed the UK decision to leave the European Union in 2020.

“On principle, it’s like companies. If you are taken over by another company, then you lose your individuality and ability to choose your own direction. So, for me, Brexit was about sovereignty and being able to decide our own course of action.

“As a small business owner, I must feel like that. I don’t want to feel part of a conglomerate. It is as simple as that ... it’s a psychological benefit.”

Dyson is now passing his knowledge on to future generations, because he wants to foster greater confidence in dealing with uncertainty. He's set up a series education facilities, such as London’s Dyson School of Design Engineering and The Dyson Building campuses in London Royal College of Art, which all revolve around the Steam syllabus of science, technology, engineering, the arts and mathematics.

“We recruit engineers because they love to change things and that’s their life ambition,” he says.

“I have also found that work experience doesn’t always help. What we need is people who need to be pioneers and not afraid to learn every day and young people I find are not scared of doing that."

Households of the future

When it comes to envisioning the household decades from now, Dyson is unsurprisingly reticent. He says an ill-judged answer could come precariously close to giving away company secrets.

"Robotics is something we are working on," he says, cryptically.

"Tidying up after children is a real chore. Clearing up after dogs and all kinds of things. Home help is becoming really important.”

One thing he is clear about, however, is that the investments and failures will keep racking up.

"You just have to accept that it's all a big risk and that you are going to be wrong sometimes," he says.

"If it always works, life will be too easy. It's all part of the thrill of it, it is a productive form of gambling that creates jobs and wealth."

Whether the Dyson Zone is one of those hits or misses, remains to be seen.