Millennia-old mosques, ancient thermal baths and grand remains are scattered across Europe as markers of the Islamic empires that once ruled parts of the continent.

From Spain to Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, France and Portugal, tourists can see impressive physical evidence of the influence of the Ottoman Empire and Al Andalus Kingdom, the two Islamic states that most obviously shaped Europe. Here are three cities where the Islamic imprint can be explored by travellers.

Sofia, Bulgaria

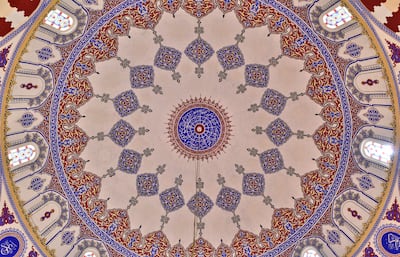

In among a cluster of Catholic churches in the capital of Christian-majority Bulgaria, a 500-year-old building stands out. I join a line of tourists entering this beautiful old structure, which is opposite the Sofia Central Market Hall in the city’s downtown area. Inside is a ceiling decorated with intricate mosaics, with a large piece of Islamic calligraphy at its heart.

This is Banya Bashi, the main mosque of Sofia. Appearance wise, this city is most obviously shaped by its historic links to the USSR and the Roman Empire. Sofia bulges with hulking remnants of those eras, such as the stunning, gold-domed Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral and the fourth-century Rotunda church, built by the Romans when their empire included what is now Bulgaria.

Yet Sofia’s Islamic history runs equally deep. For 500 years Bulgaria was under Islamic rule as a part of the Ottoman Empire. That helps explain why Banya Bashi, with its teal dome and towering minaret, is like a miniature version of the iconic Blue Mosque in Istanbul, the Turkish city that was the Ottoman capital.

Banya Bashi was created by the most famous of all Ottoman architects, Mimar Sinan, who in the 1500s designed dozens of mosques and bridges that are now tourist attractions throughout Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria. Sinan worked for the Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Great, under whose leadership this empire reached its peak, seizing Hungary and large parcels of North Africa and the Middle East.

By the time the Ottomans finally lost control of Bulgaria in the 1870s, their commanding empire was crumbling. Tourists to Sofia can learn about Bulgaria’s Islamic period at the city’s huge National Museum of History. They can also travel to the pretty Bulgarian city of Plovdiv, where the mighty Dzhumaya Mosque is in fantastic condition, more than 600 years after it was built.

Budapest, Hungary

As well as being one of Europe’s oldest zoos, established in 1866, Budapest Zoo & Botanical Garden is an oddly beautiful complex. It has a quirky melange of architectural styles, from sober communist structures to its whimsical art nouveau entrance and an enclosure that mimics a Transylvanian church.

Yet the building that held my attention once I entered this leafy space was decorated by domes, a minaret and blue-green glazed tiles. It is immediately reminiscent of the Ottoman architecture of Istanbul.

This makes sense. For about 150 years, until the late 1600s, the Hungarian capital was occupied by the Ottomans. Although this magnificent enclosure was not built until the early 1900s, long after the Ottomans departed Budapest, it stands as a reminder of the sizeable imprint of Islam on this city.

Across the Danube river from this zoo, overlooking downtown Budapest, are ancient relics of the Ottoman occupation. This area, which offers tourists gorgeous views across the city, has three popular attractions that date from the Islamic era.

They include the large Rudas and Kiraly thermal baths, both more than 400 years old. Visitors to these baths can enjoy a steam soak or a traditional hammam experience. On the hilltop above Kiraly bath, tourists come to see the stately tomb of one of Suleiman the Great’s most influential aides, Gul Baba. A popular site of pilgrimage for Turkish Muslims, this stone mausoleum is surrounded by a sublime rose garden, making it a worthy attraction for any traveller.

Cordoba, Spain

Perhaps my favourite building in all of Europe is in the overlooked southern Spanish city of Cordoba. Called La Mezquita, it is not just visually spectacular, but also unique in that it’s simultaneously a mosque and a cathedral. A monumental Moorish structure that dates back more than 1,200 years, it looks like a fortress from the outside, because of the thick, lofty stone walls that surround it.

That imposing appearance gives way, inside, to delicate design features. There are few interiors in the world more photogenic than the Mezquita’s main prayer hall. Dozens of arches embellished by stripes create spellbinding symmetry and contrast. Its soaring ceilings heighten the drama.

Just like Sofia and Budapest, Cordoba was moulded by the Roman Empire, a legacy exemplified by the 2,000-year-old Roman bridge that spans the Guadalquivir river, which runs through the city. Both times I visited Cordoba, and walked north across that remarkably old structure, it felt like I was slipping back into a bygone century, so well preserved and antique is Cordoba’s adjoining Old Town, which is home to La Mezquita.

Islamic motifs are common throughout this Unesco-listed Old Town. That’s due to the lasting influence of Al Andalus, a Muslim kingdom that from the early eighth century to the early 11th century ruled most of the Iberian Peninsula, including parts of what are now Spain, Portugal and France. Cordoba remained under strong Islamic influence until the late 15th century. Now this southern region of Spain, which includes fellow tourist favourites Seville and Granada, is called Andalusia, a reference to this key period in its history.