As a boy, Michael Englebach was taken by his grandfather to watch cricket at the Oval, the famous London test match ground.

Concerned that the hard wooden seats would be uncomfortable for a man of such advanced years, young Michael suggested fetching a cushion to sit on.

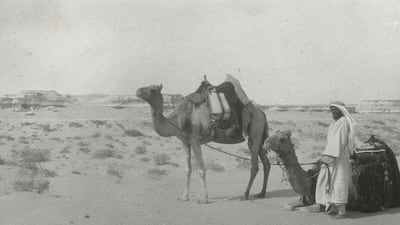

The offer was politely declined, for his grandfather was no stranger to discomfort. Mounted on a camel, he had previously explored the deserts of Saudi Arabia, crossing the vast wilderness known as Rub’ al Khali, or the Empty Quarter.

To his family, he was St John ― pronounced Sinjin ― while to others he was Harry, Jack, or even Abdullah, after his conversion to Islam.

The multitude of names point to the many facets of an extraordinary life, but all attach to the family name of Philby.

By the time Michael was born, Philby had long achieved fame for his 1917 expedition across 1,300km of desert from Al Uqair, on the Arabian Gulf, to Jeddah on the west coast and the heart of the kingdom.

In the process, he became a close friend and adviser to the Ruler of Saudi Arabia, Ibn Saud, spending much of his life there, initially as a British military officer, and eventually becoming a Muslim.

A passionate Arabist, he served in the Middle East as a civil servant and political agent, but became increasingly disillusioned with British policy in the region and fell out with the London establishment in spectacular fashion over its treatment of the Arabs, gaining a reputation as a troublemaker and dangerous radical.

Foremost an explorer, who was meticulous in his scientific observations, his greatest achievement is generally considered to be the crossing of the Empty Quarter, a test many did not expect him to survive, and which earned further plaudits from the Royal Geographical Society, which had already awarded him its Founders Medal.

All of which would have meant very little to a child. “To me, he was just grandpa,” Englebach says. “He was a very dignified figure. As a small boy looking at this grandfatherly figure, he was in every essence, the grandfather. He was bearded, he looked very distinguished and he behaved in very dignified manner.

“And he took an interest in what we were doing as grandchildren. I have very fond memories of my time with him.”

Englebach’s mother, Helena, was one of Philby’s three daughters by his wife Dora Johnston. His father, serving in the Royal Air Force, died in an air accident in February 1955, when Englebach was just six.

Englebach would visit his grandparents at their London flat at Drayton Gardens in fashionable Chelsea, where Philby was a visitor from Saudi Arabia. There was a study, filled with intriguing artefacts from his grandfather’s travels, but also the scorecards from every county and test match he had ever watched.

His grandfather, Englebach says, was a meticulous chronicler, whether of desert wildlife or the fall of wickets at a cricket match.

“He came to our school sports day when I was 10 or 11 years old, and was noting down the results of the races. At one point he said to me 'Mike, who is that boy who just won that hundred-yard race’. And he wrote down the name.

“This is what he was like. He was extraordinarily meticulous and ever curious. You could see in the way he asked questions that he wanted to know what you were up to.”

There were lunches in London, day trips from boarding school and a memorable two-week family holiday at the Welsh seaside in 1958 ― just two years before Philby’s death, in Beirut, at the age of 75.

What was not generally known at the time, and for many years after, was that Philby had a second family in Saudi Arabia. He had married Rozy, a Saudi woman some time around 1945. Some sources give her family name as Al Abdul Aziz, suggesting she was a close relative or even a daughter of Ibn Saud and much younger than Philby, possibly in her teens.

There is evidence that Philby’s son Kim, the British MI5 agent who would eventually be unmasked as a spy for the Soviet Union, knew of the marriage and the children that followed.

Whether Philby’s English wife ― there was no divorce ― was aware, may never be known. She died in 1957, and Englebach says he is not aware of the matter ever being raised.

If this seems strange to us, it should be remembered that this was a time when the demands of Empire and foreign service often meant long periods of separation for families. Absentee fathers were not usual.

It would be wrong, also, to think of his grandmother as a stay-at-home wife, Englebach says. In the 1920s she had accompanied her husband on his travels through Arabia, including Yemen, and argued furiously with another Arabist, the celebrated writer and explorer, Gertrude Bell, over Britain’s decision to anoint King Faisal as ruler of Iraq.

Rozy Philby, as she was known, had five children, although two died in infancy, a tragedy all too common in the region at that time. Three sons survived and thrived. One, Khalid Phiby, would become the UN special representative.

His grandson says he knew very little about this other, Saudi, side of the family. “My mother told me about them when I was in my late teens. She didn't have any contact, she simply said she'd heard that they were very intelligent, and that was all. And then we moved on. I wasn't really taking a huge interest.

“When I heard about him being in the Empty Quarter, I was worried about my grandpa. I thought, you know, he’s a bit old.”

It was a proposal to recreate his 1917 trek that changed everything. The Heart of Arabia Expedition, which set off this month, honours Philby’s achievement and is led by British explorer Mark Evans. The team includes Reem Philby, granddaughter of Rozy.

Englebach made contact with Reem ― the first between the two branches of the family in 60 years ― via a Zoom call. They finally met in September at the launch of the Heart of Arabia expedition in London.

“It was absolutely charming and very heartwarming,” he says. “I gather they're a very close family, and I think they're delighted to have an extended English family as well.

“Straight away I felt that there were people here who were close to me. It was a very warm meeting when we met. I'm pretty family minded, so anyone who's family to me is someone special. And so they are as well.”

There will be another meeting in January, when Englebach travels to Riyadh for the start of the second leg of Heart of Arabia to the Red Sea coast at Jeddah ― a reunion of his British and Saudi Arabian families will honour the spirit of Philby as much as any desert trek.