The oldest piece of pottery discovered in the UAE is also one of the most astonishing.

The artefact is a terracotta vase painted with undulating brown patterns that dates back to 5500 BC. The vase is on display at Louvre Abu Dhabi’s opening wing, which exhibits the oldest works in the museum’s collection. It was unearthed in 2004 on Marawah Island, 100 kilometres off the west coast of Abu Dhabi, where a number of artefacts pointing to Neolithic life in the region were discovered.

The vase was found about 1,000 kilometres away from its culture of origin.

“It’s the earliest evidence of ceramic in the UAE and in relatively complete form,” Amna Al Zaabi, senior curatorial assistant at Louvre Abu Dhabi, says.

“The decorative patterns on the neck and body of the ceramic indicate that it was not produced locally. It was brought from Mesopotamia, or southern Iraq today.”

The vase, Al Zaabi says, suggests the Neolithic residents of Marawah Island could have been in contact with their neighbours as early as 5500 BC.

The artefact, on loan from the Department of Culture and Tourism — Abu Dhabi, has been on display at Louvre Abu Dhabi since its opening in 2017. When it came to expanding upon the historical depth of the UAE, it was perhaps one of the museum’s most insightful pieces.

However, a series of loans that were added to the exhibit in November further delve into how the region was a crossroads for culture even thousands of years ago. The artefacts are on loan from several institutions from around the country, including Zayed National Museum, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Al Ain Museum, Dubai Municipality, Sharjah Archaeology Authority, Department of Tourism and Archaeology in Umm Al Quwain and the Department of Antiquities and Museums — Ras Al Khaimah.

Among these artefacts are three necklaces on loan from Ajman Museum. Made out of minutely carved chalk beads, the necklaces date back to 3000 BC and shed light on the customs of the Bronze Age inhabitants of the UAE. They were discovered in Ajman’s Al Muweihat archaeological site.

“These are examples that would be produced locally,” Al Zaabi says. “The material used here is humble but it’s interesting to see how fine and precise each bead is.”

The necklaces date back to the Umm an-Nar period. The Bronze Age culture existed in what is today the UAE and Oman and was a key trading intermediary between civilisations in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.

Much like other similar accessories, the necklaces were unearthed in a collective tomb that was characteristic of the era.

“You would find hundreds of bodies buried in the same tomb over generations with their personal belongings,” Al Zaabi says.

Another newcomer in the exhibit, a comb dating back to 2300 BC, had also been interred along with its former owner. Made of ivory, it was an import and could have originated in the north of India, Al Zaabi says. It was discovered in a grave in the archaeological site of Tell Abraq in Sharjah and features broad, flat teeth as well as circular designs on its handle.

“It’s a common decoration,” Al Zaabi says. “You can also see it on the vessels displayed alongside. It was a very popular motif during that time."

The artefacts, Al Zaabi says, gesture towards a unique time in regional history, giving a view of the networks ancient cultures had developed.

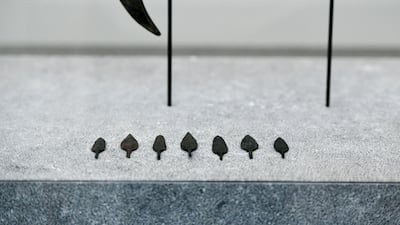

A set of seven incised iron arrowheads point to the culture of the region during the Iron Age. Dating back to 1500 BC, the arrowheads were discovered in Qidfa, Fujairah.

“They are incised with geometric decorations,” Al Zaabi says. “There are studies by archaeologists trying to interpret these motifs. Qidfa was an oasis that was excavated in the late 1980s. There, they also found other weaponry such as daggers.”

One of the museum’s most visually compelling objects related to the region’s ancient history is a dagger that was discovered at Dubai’s Saruq al-Hadid, the same archaeological site where the ring behind the Expo 2020 Dubai logo was found.

Made of a copper alloy, the dagger’s hilt is shaped like a lion, mid-pounce. What is peculiar is the tilt of its blade, which doesn’t bend as a pointed beak but horizontally.

“We know at this time in several areas around the world weapons would be considered offerings or would be buried with the warrior,” Al Zaabi says. “We don’t know exactly why the blade is curved. Some archaeologists say that it was part of a ceremony, where the blade would be offered and bent. This is common across many cultures where items would be fragmented or broken for offering. It could also be that it is simply a defective product.”

Some of the other locally excavated include a ridged-glass dish dating back to 100. An import of the Roman Empire, the dish was discovered in the archaeological site of Ed-Dur in Umm al Quwain.

“The Roman Empire was one of the empires that successfully managed to influence many cultures because it had many provinces or through trade,” Al Zaabi says. “We’ve found in the Gulf area, especially in the UAE, many objects of trade that came from the Roman Empire."

He says the sites, which date between 200 BC and 200, suggest it was a port city and glass objects make up 8 per cent of the objects found — though Al Zaabi says the dish is the most complete.

The artefacts are often juxtaposed with similar finds from other parts of the world. The dagger, for instance, is displayed alongside axe blades from Iran and North Ossetia dated between 700 and 1000 BC, as well as a mace from France dating back to 800 BC. The glass dish, meanwhile, is displayed beside glass goblets and cups from France.

“We talked about how to put such important pieces from our history within the universal narrative of Louvre Abu Dhabi,” Al Zaabi says. “We wanted to create dialogues between the works of art.”

The collection, Al Zaabi says, which has only become possible with the collaboration between the country’s archaeological and cultural institutions, is aimed at illuminating a period of local history that is not commonly known about.

“The archaeology shows that since the beginning, we’ve been connected with people. We haven’t been isolated. We were producing and exchanging. That’s the message we would like to deliver.”