As Saleh Farah's flight approached Abu Dhabi, he looked down and saw what appeared to be a village with huts and Bedouin-style tents dotted along the coastline.

It didn't look dissimilar to the surroundings back in his native Sudan, and couldn't have been more in contrast to the Abu Dhabi that lays before Mr Farah today — 55 years on.

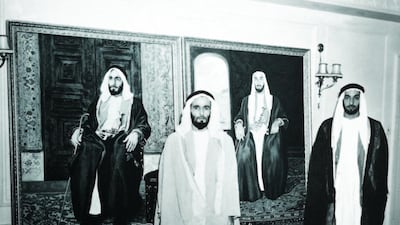

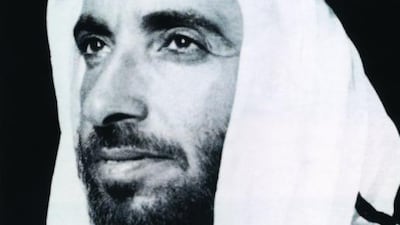

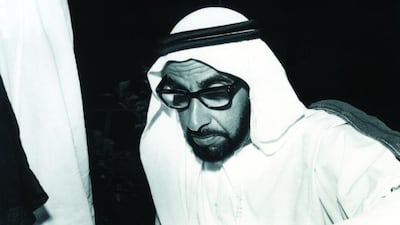

The following years and decades would see him perform a vital role in the formation of the UAE. He worked closely with the UAE's Founding Father, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, and developed a bond with a country that has become his home.

He sat down with The National to reminisce about his extraordinary life and experiences.

Answering a job advert

A law graduate and one of the first Sudanese to be called to the English bar in London, Mr Farah, now in his 90s, spent his early working years as a civil servant in Khartoum's government.

He resigned in 1966, having been at loggerheads with the establishment over elements of its bureaucracy. The British Embassy in Khartoum offered him a position as one of the protectorates of Lahij, just north of Aden in what was then South Yemen, which was still part of the British Empire. However, he foresaw unrest and turned it down.

It was a newspaper advert placed by Sudan's Ministry of Labour that prompted his life-changing move.

Sheikh Zayed had big plans for Abu Dhabi following its oil discoveries and sought talent from overseas to help to realise his vision.

Mr Farah interviewed in Sudan for the position of head judge in Abu Dhabi and was offered the job in November 1966. He was then told he would have a dual role: legal adviser to Sheikh Zayed and Director of Justice.

Life in Abu Dhabi

Travel to and from Abu Dhabi was an extended affair. Mr Farah first flew from Khartoum to Beirut for a several-hours stop over, before boarding a British Overseas Airways Corporation flight to Bahrain, where he spent the night. The following morning, his final leg to Abu Dhabi was aboard a Gulf Air Fokker plane that had infrequently scheduled flights to the emirate.

They landed in an area off what is now Muroor Road near the junction with 17th Street within what is today the Abu Dhabi Media complex. It was the only place in which the surveying team could find 1,000 metres of ground firm enough to hold the weight of an aircraft.

He arrived with only basic toiletries, some clothes, his Quran, and a readiness to get to work.

Sheikh Zayed was in Pakistan at the time, so his older brother, Sheikh Khalid, was in charge in his absence.

Mr Farah was taken to meet him at Qasr Al Hosn, before being set up at the guesthouse — situated where Al Mariah Cinema now stands on Al Nadja Street.

His first meeting with the Ruler came a few weeks later. But this time, Mr Farah had been given his own car, only to be put off driving almost instantly because of the difficult driving conditions on sandy terrain.

He flew to Dubai to meet Sheikh Zayed, who had returned from a private visit abroad, and accompanied him on the 20-minute return flight back to Abu Dhabi.

“He welcomed me very warmly with a handshake and asked how I was,” Mr Farah told The National. “He only had a couple of minutes with each person on the flight and, although it was a short introduction, it was from this day that I started spending most of my time around him.”

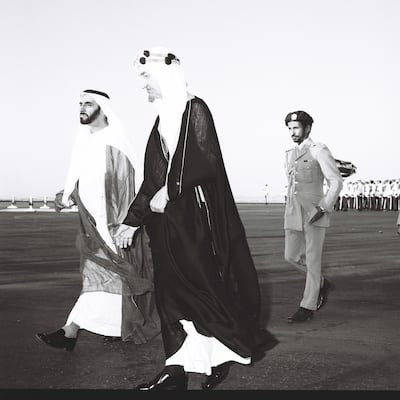

About two months into his new post, he accompanied Sheikh Zayed to meet King Faisal of Saudi Arabia for discussions over land borders.

He also accompanied the Ruler to Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, the UK and Spain, but most prominent in his memory are two trips to Iran to meet the Shah.

As Abu Dhabi was still a British protectorate, Mr Farah worked closely with British agents.

“I found the British agents to be respectful with me in person,” he said. “I was not only a lawyer, but a barrister, and this membership of the British inns of courts was quite an asset.”

It wasn't always a smooth relationship, however. A letter from Archie Lamb, of the British Political Agency in Abu Dhabi, in 1968 said Mr Farah “seems to take delight in being obstructive”.

“Obstructive presumably to what the British wanted as law and which was not suitable for the region,” Mr Farah said.

A new legal system

When Mr Farah arrived in Abu Dhabi, the British had been using their own legislation for almost two decades. His task, as a judge and director of the Department of Justice, was to establish a fully fledged legal department.

This entailed setting up a judicial system with a court of appeals consisting of three to four judges, excluding the initial judge ruling in any given case. The system exists to this day, albeit much expanded to accommodate the growing needs of the country.

“There was no documented legislation when I arrived, but instead there were customs, so what we tried to do was to add laws to to these,” Mr Farah said.

A hurdle for the legal development team was that anything concerning Abu Dhabi was dealt with under the British court and protectorate laws were handled by a British judge periodically visiting what were then called the Gulf Trucial States from Bahrain. At some point, the British gave jurisdiction to Abu Dhabi regarding all nations, with the exception of Europeans, Americans and members of the Commonwealth.

“To win jurisdiction over the total population, we had to secure British agreement to our suggested laws, which would also apply to the groups previously exempted by the British under the Gulf Trucial States agreement,” Mr Farah said.

When submitting new laws to Sheikh Zayed, Mr Farah required the acceptance of the British agent. The judge's uncompromising stance regarding Abu Dhabi and “stubbornness” is recorded in the British archives.

Mr Farah was with Sheikh Zayed almost every day. He said the Ruler would begin his day at 7am and then there would be a break for lunch, when Mr Farah would go home. He would return for Sheikh Zayed at 4pm and stay until about midnight, sometimes leaving at 3am or 4am.

“Despite staying up so late and having very little sleep, I never felt tired as it was a different life to that of working in an office in Khartoum,” Mr Farah said. “I thought I was going to be in court trying cases after they requested a judge from Sudan, but instead I was mostly developing laws for the country. After all, there weren’t many crimes being committed.”

The meeting in the desert

In January 1968, a year after Mr Farah's arrival in Abu Dhabi, it was announced that the British would be pulling out of the region.

Steps towards closer co-ordination between Abu Dhabi and Dubai began immediately. Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, then Ruler of Dubai, received Sheikh Zayed and his advisers on January 10, 1968, to explore the possibility of consolidation and find a common policy to bind the states together.

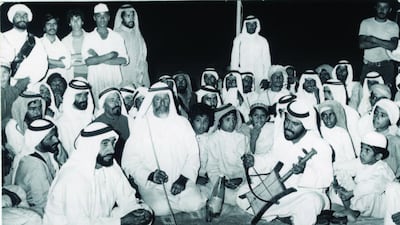

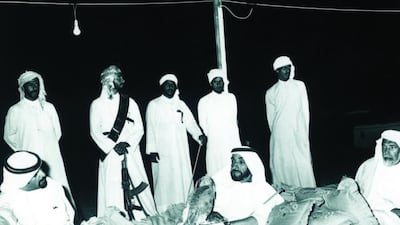

Then came the significant moment in history on February 18, when Sheikh Zayed and Sheikh Rashid met again. This time, it was at a campsite in the desert at Seih Al Sedira, a small hill on the Abu Dhabi side of the border and close to the community of Al Sameeh.

Two tents were set up — one for hospitality and the other for private meetings.

“I was one of the few who were there … I didn’t know what was going to come from this meeting beforehand, there had been no indication,” Mr Farah said.

“They were talking in one tent and came out and asked us to draft a statement saying they had agreed on a union whereby the other five states were invited, plus Qatar and Bahrain.”

A letter from the Gulf Political Resident Stewart Crawford noted the drafting session, which included Mr Farah acting as the Ruler's Legal Adviser.

The signing was known as the Union Accord. It included a unified flag, unified currency, federal unity in defence, internal security and foreign policy, plus in common immigration, education and medical systems.

Mr Farah represented Abu Dhabi on a liaison committee set up to co-ordinate the contact between the emirates. He was the expert from the emirate given the task of drawing up the Constitution.

The Constitution was a complicated process and Mr Farah once again found himself at loggerheads with the Qataris, who at this point were set to be part of the formation.

A frosty relationship between Mr Farah and Qatar's legal adviser, Dr Hassan Kamel, ensued and is recorded in the Arabian Gulf Digital Archive within correspondence from British agent Mr Lamb.

On one occasion, the Emir of Qatar, speaking to Sheikh Zayed referred to Mr Farah as a foreigner. Mr Farah said Sheikh Zayed retorted: “He belongs to Abu Dhabi and not Khartoum. He is not Sudanese but instead a member of the ruling family.”

The meetings eventually touched on a suggested draft for the Constitution, which was later adopted. Mr Farah and Adi Bitar of Dubai were given the task of drawing up a joint statement of the agreement for the union.

Finally, after 47 months of discussions, the UAE was born.

New era, new passport

Having flown into Abu Dhabi on a Sudanese passport and then being issued with an Abu Dhabi one for his travels with Sheikh Zayed, Mr Farah was one of the few at the time who was, as part of a special decree, naturalised for services to the nation. This is an honour that has never left him.

After Sheikh Zayed’s Ministry of Justice moved to the Federal Government, Mr Farah was made legal adviser to the President with an office at the Presidential Palace.

Having continued in this role through the 1980s, he retired aged 60 in 1991. He remains in Abu Dhabi, now a father to 10, a grandfather to 16 and a great grandfather to three.

“Having been in the service of Sheikh Zayed, I felt that I couldn’t stay on in law after leaving service with Abu Dhabi,” Mr Farah said.

“I chose instead to retire to my house from which I could visit people and they could visit me. There were job offers, but they were difficult to accept for the same reason. As the legal adviser to Sheikh Zayed, they thought they would have someone of consequence, but that wasn’t for me.”

Today, he marvels at the changes that have taken place in Abu Dhabi. Without forgetting his homeland, he is proud of his involvement in the formation of the country and to have witnessed the progress that Sheikh Zayed achieved.

“We are fortunate to have lived Sheikh Zayed’s dream for his people and which was continued by the late Sheikh Khalifa and presently the torch continues to be admirably carried by Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed,” Mr Farah said.