We migrated to Pakistan in 1948, about a year after the Partition of India. For some time, all 17 of us in my immediate family lived in a two-bedroom home in Karachi. My father then built Sibtain Manzil, a two-storey house in Nazimabad, an arid strip of land about 10 kilometres from downtown Karachi.

By the time we moved into Sibtain Manzil in 1953, Nazimabad had become both a home to immigrants like us who sought a new life, and a hub for the cultural intelligentsia. And so, it wasn’t surprising to see my uncle, Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, or Sadequain as he is better known, among the cultural luminaries walking along Nazimabad’s streets.

He was attentive and intuitive and knew how to make someone feel special. He was intellectually astute, a good listener and thinker able to draw crowds in like a gravitational force. People would show up unexpectedly at Sibtain Manzil, eager to have a chat or receive a painting, which Sadequain would dispense freely.

A profoundly generous man, I remember an incident in the mid 1950s when a rickshaw driver without a rickshaw rang the doorbell and asked for help. “How much is a rickshaw?” Sadequain asked. “About 800 rupees sir,” replied the driver. Sadequain promptly bought him a rickshaw. “How can I ever repay you sir?” asked the driver. “Don’t repay me. Just take me to the centre of town tomorrow morning and bring me back in the evening,” replied Sadequain, who later painted a portrait of the driver resting in his rickshaw.

As a child, Sadequain would draw in charcoal on the walls of the family home. No matter how many times he got reprimanded, it didn’t stop him from redrawing and asking family members about their dreams to illustrate. “I was born to paint,” he would tell me. “And I have a photographic memory.”

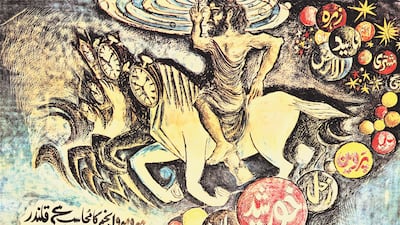

Though we hail from a family of Quranic scribes, which considered calligraphy an esteemed practice, Sadequain had been told that he couldn’t make a living as an artist. That never deterred him, and his talent was nurtured in the early 1940s when he joined his brother at All India Radio and worked as a calligrapher-copyist. After graduating from Agra University in 1948 and moving to Pakistan, he worked for a time as a college teacher and at Radio Pakistan before committing himself strictly to his artistic practice. Sadequain was also a profound poet and had begun authoring rubaiyat or quatrains in his early years; later, he would illustrate his poems and publish books.

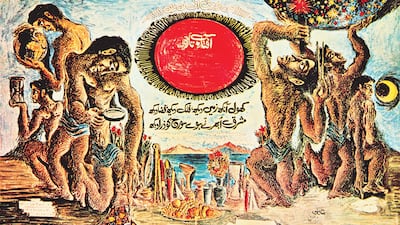

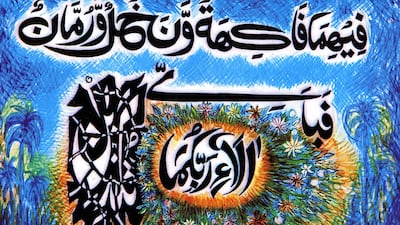

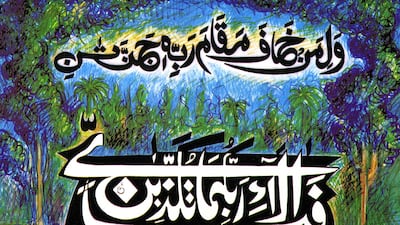

It’s incredible that he mastered and merged painting, calligraphy, poetry and murals. I am fascinated at how he propelled calligraphy as a mainstream art form, producing figures and metaphors from script.

Although he took me to see movies such as Ben Hur and The Longest Day, what I most enjoyed was watching him paint in his bedroom that doubled as his studio. I often fell asleep because it was such a hypnotising experience.

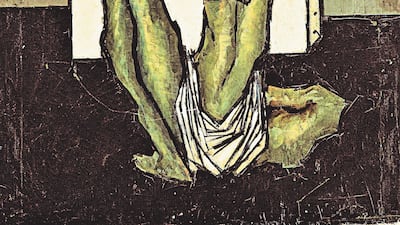

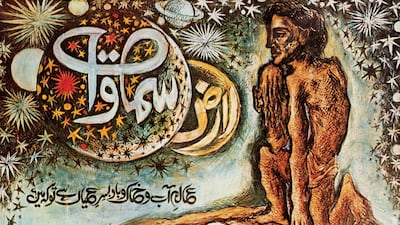

I think Sadequain was a performance artist, too, using his body, mind, paints and canvas to deliver an awe-inspiring artwork. I saw how his letters and forms swirled on his canvases, and I felt that he had a divine connection with them — not solely because some of the text was Quranic, but rather, that the individual letters spoke to his soul. He often described each letter as having its own personality, as though it were a person with good moods or dark temperaments — and he illustrated them as such.

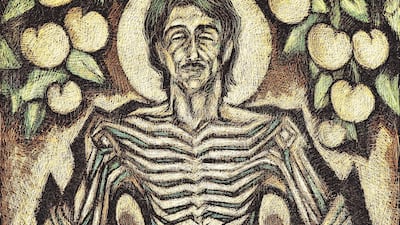

When the painting was complete, it seemed as though Sadequain and his letters morphed, becoming one: an opinionated work of art that celebrated calligraphy and defended the common man. Through his calligraphic figures and landscapes, he always focused on the human condition, addressing moral, political and social issues. It was his mission as an artist.

Sadequain caught the attention of renowned art critic and diplomat Hasan Shaheed Suhrawardy, who introduced him to his brother, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, prime minister of Pakistan from 1956-1957 and a patron of the arts, and in whose home hung works by Sadequain.

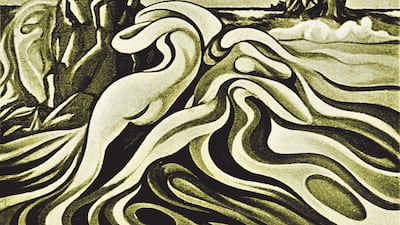

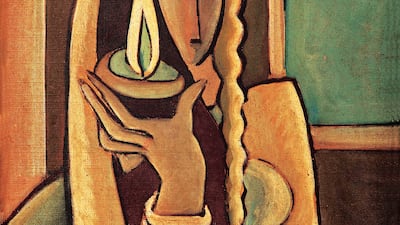

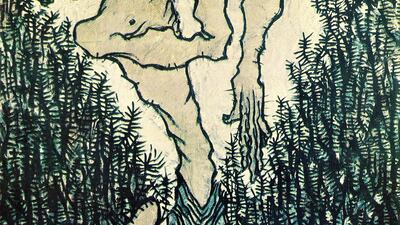

Exhibitions and commissions followed — some patronised by the state — as did a fascination with the work of Picasso, whose influence can be felt in works from the late 1950s and early 1960s. Around this time, Sadequain secluded himself in Gadani and a new element indigenous to the seaside town began to appear in his canvases: cacti, which he adopted as an allegorical symbol of aggression and humanity’s resistance and resilience in the face of hardship.

In 1960, Sadequain was invited by the International Association of Plastic Arts in Paris and won an award at the second Biennale de Paris for a painting he had made at Sibtain Manzil. The biennale subsequently granted him a scholarship, an experience that led to successful exhibitions in France, the UK and the US, and in turn, a wider collector base.

Sadequain regularly wrote to my father and mentioned his struggles and triumphs, and asked about each family member. Of his nieces and nephews, he wrote: “Tell them not to study too hard, tell them to play outside.”

Many believe that his Paris years birthed some of the best works of his career, one of the most significant being a commission to illustrate a new limited-edition of French author and Nobel laureate Albert Camus’s 1942 novel, L’Etranger (The Stranger). In Paris, he painted the city’s scenes in greys and blues, effecting his oeuvre with a greater sense of expressionism and a move towards abstraction. In 1967, he departed Paris abruptly and left behind belongings and paintings. In 2011, I was able to locate more than 500 abandoned paintings in attics, basements and storage facilities.

Sadequain returned to Karachi, and continued to dazzle with his art and spirit, focusing more on calligraphy, publishing his poetry and completing more murals — an art form he had begun in 1955 and in which he completed dozens in Pakistan, India, the Middle East, Europe and North America.

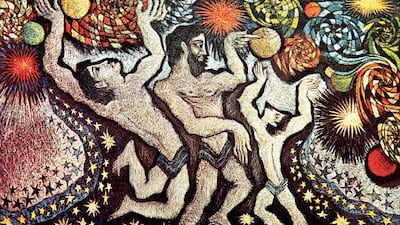

Murals had further cemented his standing as an artist of the people with their empathetic messaging. Notable ones include the monumental The Saga of Labour (1967) for the Mangla Dam powerhouse that pays tribute to labourers, while the 1968 Quest for Knowledge at the Punjab University Library prizes education through its illustration of young men and women holding a "key to learning". Sadly, many murals have either disappeared or been damaged because of neglect, one of which is at Frere Hall, a Venetian-Gothic structure whose ceiling Sadequain had painted, and dedicated to Karachi’s citizens, but which he didn’t complete owing to his untimely death in 1987.

For all his generosity and joie de vivre, Sadequain had a myopic vision as far as his own legacy is concerned. It is tragic that a man who gave so greatly has not been celebrated as much as he deserves. This is why I established the Sadequain Foundation. To date, it has published 25 books on Sadequain and staged more than 100 seminars and exhibitions around the globe. It’s so we don’t forget who spoke for others.