Mohammed Alnaas on Sunday became the first Libyan and youngest author to win the International Prize for Arabic Fiction when his novel, Bread on Uncle Milad's Table, beat five other shortlisted works for the $50,000 prize.

Speaking from the sidelines of the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, days after winning the coveted award, Alnaas says he is still buzzing with excitement, and needs time to reflect on how the accolade will affect his life.

“It’s overwhelming, and I still haven’t had the chance to wrap my head around it,” he says. “It seems like everything in my life has changed in one moment.”

As well as the monetary award, the International Prize for Arabic Fiction guarantees an English translation for winning works. Alnaas says he is eager to see Bread on Uncle Milad's Table, as well as the issues it explores, being given a wider audience.

“The international reader needs to know what contemporary Arabic fiction has to offer,” he says. “I think the novel has some new questions to add in the discussion about equality and masculinity, I would love to see the book translated, not just into English, but to all written languages of the world.”

'Bread on Uncle Milad's Table'

Alnaas had two years of false starts when trying to write Bread on Uncle Milad's Table.

He first conceived the novel in 2018, and although he had tried to flesh out its character and plot at his writing desk, for a while all he had of the book was its title, which was inspired by an old Libyan proverb, and the protagonist it names.

In the end, to know how to write a novel around a baker, he had to learn how to make bread.

Breadmaking had become a popular pastime in the pandemic era as many across the world turned to flour as a way of coping with social restrictions. Living in Tripoli, however, Alnaas also had to deal with chronic power cuts and the sounds of not-so-distant gunfire and bombardments. The author would go through a kilogram of flour every day, trying to knead away the encroaching death and war while figuring out how to write Bread on Uncle Milad's Table.

As his breadmaking skills improved, he felt confident he had found a way forward. In April 2020, he wrote the first line of his novel. He wrote feverishly for the next six months, until the story found form.

author

“I wasn’t ready to let go of the idea that the character of Milad should be a baker,” Alnaas says. “Because I was ignorant of baking techniques, I began to research and learn all the types mentioned in the novel, even croissants, which are one of the most difficult baked goods to make. When I did, the novel opened up for me.”

The novel begins with Milad striving, yet failing, to embody the ideal of masculinity as his society views it. After becoming engaged to his sweetheart, Zeinab, he decides to be himself. He performs tasks his society reserves for women, such as breadmaking, while Zeinab works to support the family, but soon finds out he's being mocked in the village.

Bread on Uncle Milad's Table is an exploration and dismantling of preconceptions of masculinity, especially in a society ruptured by conflict. Alnaas says he intended the novel to prod “Arab societies in general to open their hearts and minds to what’s different from the stereotypical”.

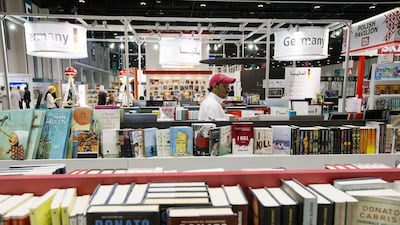

Scroll through the gallery below to see photos from the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair 2022

The novel was released in June 2021 by the publishing house Rashm.

“Milad was different from his community, they didn’t allow him to live freely as he wanted, they forced him to be like them, and I think that’s what destroys societies, that communal and systematic force and urge for everything to be just the same, I lived my childhood, where everything looked the same, we looked the same, and we looked like our 'Big Brother', it wasn’t good,” he says.

“After the novel was published, I received a comment on Goodreads, in which one reader says how much he saw himself in the character Milad. This is what makes me write, for the reader to interact with the novel, whether with love or hate; this means that I have fulfilled their trust.”

Celebration among Libyans

Alnaas’s win has stirred a festive storm among Libyans online. The achievement is being celebrated as a turning point in the country’s literary scene after “decades of dictatorship, war and harsh changes in the social fabric”.

“The literary scene at home really needed a winner in the Ipaf,” he says. “That’s why when the winner this year was announced, they celebrated and are still celebrating. It’s the first time that a literary event becomes viral in the Libyan social media scene, which is a big thing.”

The young author also says it feels “weird” to be the “first '90s kid to win”, but that he hopes the achievement inspires a new generation of Arab writers.

“I hope that what I’ve done here can unleash the creative talents of my generation and the generations to come in the Arab world,” he says. “I believe we will hear new strong voices, who will offer to the world a new look into Arab literature, it will blow your minds — not physically, don’t worry. [But] trust that.”

A 'bold voice' yet to come

Despite, or perhaps because of, his success, Alnaas is not ready to leave the world of Bread on Uncle Milad's Table. The author has recently finished a manuscript based on Lutfi Al-Malawi, a character from the novel, a work that's sponsored by the Arete Foundation for Culture and Arts in Libya.

“The novel's arrival at this stage of the Ipaf award means a space of financial stability, in addition to marketing the rest of what I will write in the future. As for the book itself, prizes are not the only value from which one can determine the value of a particular book. The book’s endurance over time is what makes it valuable. That is why we still read many great novels that did not win prizes.”

On how he sees the landscape of Libyan literature, Alnaas says he is witnessing a marked rise of young writers defying the status quo, something he welcomes.

“Literature in Libya on one hand suffered decades of marginalisation and censorship during the rule of Muammar Qaddafi. It underestimated the writers and poets of that era. The regime stereotyped them and made them in some way employees of the state, waiting for its giving and granting,” he says. “Meanwhile, it also fought private businesses and publishing houses. They made publishing affiliated with the state, in addition to the severe censorship that the regime was exercising at the time.”

Now, he says, there is a tendency towards liberalism among young writers, but this is offset by the remnants of the older system and the rise of a militant wave that fights literature and freedom of speech.

“Young Libyan writers are now looking to spread their literature across the world. I think that, in the next 10 years, Libyan literature will have a voice that no one has ever known before, a voice full of wounds across a hundred years — since the Italian occupation — but a bold voice.”