A small Damascene bazaar in a serene courtyard of the 16th-century building complex of Takiyya Al Sulaymaniyah – named after the Ottoman leader Suleyman – is bustling.

The mosque and its two slim minarets – built in 1554 by Ottoman architect Sinan – is a must-see attraction in Syria's capital, and the marketplace in front of them remains one of the city's hidden gems.

A plethora of antique souvenir shops, old carpentry stores and copper plate makers hide the biggest jewel of all: one of the last remaining brocade sellers in the country.

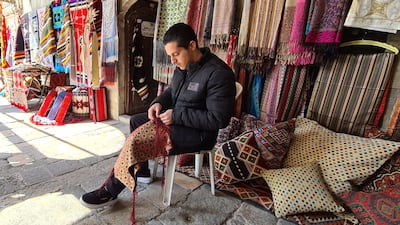

brocade trader

Maher Derki, 17, sits in front of a shop that has been in his family for more than half a century, showing off different brocade fabrics and rugs.

His family has been in the brocade trade for almost 100 years, beginning with his grandfather, Mohammed Saleem Derki (Abu Diab).

For a teenager, Maher is well-versed in the intricacies of brocade, a mix of natural silk, silver and gold woven fabric that has attracted the most regal of customers, including Marie Antoinette and Queen Elizabeth II.

In fact, Queen Elizabeth's famed wedding dress, featuring a drawing of two love birds kissing, was made using brocade fabric imported from Damascus.

“A real metre of brocade depends on whether the silk is natural or not and whether it’s done by hand or machine,” he says with authority.

“The handmade original, if you can even find some in all of Syria, is scarce; there aren’t 100 metres of handmade brocade left in the country. And even then, that’s almost invaluable.”

Brocade is strongly associated with Damascus, yet it is an Italian name derived from the word “pocatello”, which denotes a silk cloth embellished with silver or gold threads.

While Syrians have been manufacturing this highly detailed and colourful thread since the 11th century with Chinese imported silk, the town of Dreikish in Tartus is famous for raising silkworms.

But a lack of tourism and decreased demand for brocade after the outbreak of war in the country has ripped the industry to shreds.

“Most of what is present today is the brocade made by machines,” Maher says. “The handmade types are almost entirely extinct, they don’t make them any more. It’s not impossible to revive it, but it needs a significant effort.”

brocade trader

As we talk, Maher’s father, Samer, whose name graces the shop entrance, calls.

“I don’t go to the store any more,” he says with a heavy voice. “I have three factories and have to keep up making materials, but anyone who is looking into brocade, we are supportive of and will help those wanting to revive this tradition.”

When asked whether he thinks the business is dead, he says: “Brocade needs an incubator, brocade is the idea of a machine and this machine is easy, we can create 200-odd machines and get people to start doing it over again. It needs a generation.

“There is brocade in Pakistan and Turkey, but it’s not the same as here.

“If you want to go back to handmade times, it needs marketing because you and I are unable to restore this at the time.”

It’s difficult to fathom that such a central part of Syrian history needs marketing.

“Before the crisis, we used to go to all the expos and Paris, London, we were everywhere,” Samer says. “Even in the Gulf, we would spend months in expos, whereas now, we don’t have that type of exposure any more. It’s all gone.”

Samer’s father helped make the fabric for Queen Elizabeth's wedding dress in 1947 under a special request from the Syrian embassy in London. Shukri Al Quwatli, the president at the time, obtained 200 metres of brocade with 10-karat gold threads.

“My father was an innovator in this field. Even the wedding dress worn by Elizabeth, several people worked on it to get that end product fabric. My father was in this project from A to Z; he worked with Al Naasan, where the dress fabric came from.”

The war signalled the beginning of the end for the brocade trade, as the focus shifted away from heritage and crafts.

However, the preservation and revival of such important elements of Syria’s history can only pave a path towards a more certain future.