Trunks and treasure chests in the attic may be a thing of the past, but many of us have old things lying around the home – some revered, others forgotten. A war-era watch, granny’s favourite utensil, a handwritten document that’s 100 years old, jewellery boxes, lamps and yellowing books all reside peacefully, carrying memories of the past. If these inanimate things could speak, what tales they would narrate.

Trip down memory lane

Tracing family history and social ethnography through heirlooms, collectibles and objects of antiquity was the idea behind the creation of the virtual Museum of Material Memories. It was founded in 2017 by Aanchal Malhotra, an oral historian and author of the Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory, and Navdha Malhotra, a ceramic artist and digital communications expert.

oral historian and co-founder of the Museum of Material Memory

When researching for her book on objects that migrated during the 1947 India-Pakistan partition across the border on both sides, Malhotra received requests from people to visit them to see their objects. The creation of the museum came about when Malhotra was thinking up ways to build an organic archive to preserve the material history that was based on submissions across the Indian subcontinent and its diaspora, and that was part of families for generations

Extending the time frame to 1970 broadened the project’s historical and geographic scope, allowing communities not affected by the partition to contribute to the archive.

“Every one of us should be empowered keepers of our own histories, whether they be oral or material, and we hope this contribution format will encourage people to actively archive personal history,” Malhotra tells The National.

Accordingly, the Museum of Material Memories is a retrospective of heartfelt stories and cherished possessions, all with a stamp of antiquity. Anyone around the world can submit objects, as long as they originated in the Indian subcontinent. It chronicles the culture, customs, conventions and language of a vast and diverse region. Apart from the historical value of the objects, the stories owners share are equally enthralling.

Layers of history

“The idea of investigating history through personal objects is brilliant,” says Priyanka Sacheti, who contributed a 100-year-old purple lehenga that belonged to her paternal grandmother. A made to-order piece crafted in Varanasi, it was Sacheti’s great-grandfather’s gift to his daughter more than a century ago.

Remembering the visits to their ancestral haveli in Ajmer, Rajasthan, during the holidays, Sacheti says the annual ritual of gently unwrapping the lehenga stored in her mother’s wardrobe “spoke profoundly about its preciousness”. She is fascinated by the conversations that occur by way of objects, and that excavate memories that may otherwise remain unexplored.

Sacheti was 19 when she wore the lehenga for the first time. “It was like wearing history. Apart from its personal and historical significance, it also has a feminine cultural heritage value that goes back three generations,” she says, appreciating the connection between her grandmother, mother and herself folded within the layers of the lehenga.

Worth their weight

Khushveen Brar was very young when her great-grandmother and grandmother died. “I felt envious of my older cousins who have fond memories of both the grandmothers,” she says.

Conversations with her mother created a yearning for the connection she couldn’t have. So Brar requested that her maternal aunt bequeath some of their belongings to her, and thus she came into possession of a salwar with a “ginormous ghera” and a pair of silver anklets. Reading a story of a similar panjeb (anklet) on the museum’s website encouraged Brar to explore the possibility of contributing her story.

Both the pieces she inherited are almost a century old and are thought to be a part of the wedding trousseaus of her grandmothers. The emerald-green salwar made of satin silk is almost 2.5 metres long.

The anklets have a delicate interlinked design with flower motifs on the clasp, and weigh 336 grams as a pair; each is 30 centimetres long.

Brar is so possessive and respectful of the objects that she doesn’t want to have them altered. “The thought that my grandmothers had touched them and now I am touching them is so fascinating that I don’t want to change. I feel connected and want to cherish their fingerprints.”

Roots and shoots

Pistols aren’t normally associated with veneration. However, Anviti Suri can’t help but cherish her Colt pistol, which was manufactured on December 22, 1903, in Hartford Connecticut, and acquired by her grandfather in 1960 to feel safe while travelling, which is now on view on the Museum of Material Memories.

Suri vividly remembers her grandfather dressed in a white kurta-pajama taking out the pistol every Dusshera, an Indian festival where it is customary to do an astra puja, or special prayer, for weapons.

Suri also initiated conversations with her grandmother, father and uncle about their memories of the pistol. She says she is amazed by how the same object can generate unique personal recollections by its sheer presence in a home, minute details that are far more fascinating than a systematic chronological narration.

Table of contents

Objects have a destiny, too, as in the case of Madhumita Gupta’s dining table upon which three generations of the family have eaten five-course Bengali meals every day for years.

contributor to the Museum of Material Memory

Crafted in the late 1950s, the table came to the family when an errant tenant, a skilled carpenter, fled the house in Itarsi, Madhya Pradesh, leaving behind a few pieces of furniture. Gupta’s grandfather confiscated the polished teakwood table and passed it down to her mother. The piece became an indispensable part of many birthday parties and, Gupta says, has been privy to many conversations, both happy and challenging.

The table originally consisted of foldable side panels that were removed and given to Gupta when she set up her own home after getting married in 1985. The side panels were joined together to create another table that now belongs to her nephew.

That second table has a plank running through the centre that can be used as a footrest. The plank also carries teeth marks of a family pet who chewed on it, as Labradors are wont to do. “My nephew refuses to get it replaced, to retain the dog’s memories,” says Gupta, who believes that while this table wasn’t originally crafted for the family, it was definitely intended for them.

The pen is mightier …

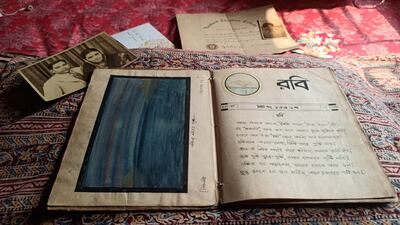

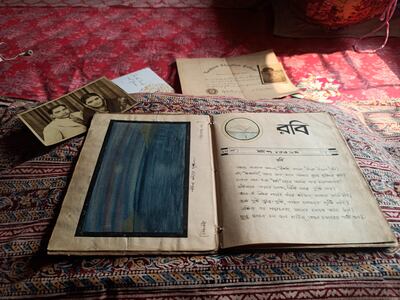

A college project and an online course about old artefacts ignited an interest in such objects for Dr Debika Banerji. While digging out old stuff for a course assignment, she remembered an old handwritten magazine lying around the house.

Robi Magazine is a document written out by Banerji’s grandfather in 1929 during his college days, and she says the penmanship speaks eloquently about the previous generation’s immaculate writing skills and perfect lettering.

The magazine is about 30 pages long, and contains poems, illustrations, cartoons and two watercolour sketches, all faded with time. The worn-out cover has saved it from disintegrating completely, and this is the only surviving copy, as far as Banerji knows, which has travelled to Lucknow, Pune, Kolkata and Jalandhar along with her grandparents.

Trials and triumphs

The Museum of Memories is not without its obstacles and setbacks. Crowdsourcing objects, which is the museum’s USP, can be challenging, says Malhotra, as the ongoing search for rare objects and their stories is crucial for success.

The co-founders also have to rely on strong visuals – photographs and videos – to captivate readers and establish a connection with the objects, but this can sometimes be a technical challenge.

The pandemic, however, did help the cause as families in lockdown had conversations as never before, then reflected on and articulated their thoughts in journals, thereby increasing submissions. Malhotra encourages others to delve into their own histories because “conversations with parents, grandparents, great uncles and aunts, will lead you to make connections, tether you to events of history and spark memories you could not imagine”.