At 3pm as the call to asr prayers rang out across the old town of Manama, Ebrahim Dawood Nonoo unlocked the gates to the Gulf’s only Jewish cemetery to tend to his family’s graves.

As president of the Association of Gulf Jewish Communities, one of Mr Nonoo’s many daily tasks is to preserve the heritage and traditions of the religion's more than 140 years in Bahrain.

Just a few months ago, the cemetery, tucked behind a high, crumbling wall, was left overgrown and dishevelled as nature began to reclaim the land.

Thanks to a new perpetuity fund to maintain the cemetery, the sacred land where about 80 Jews are laid to rest is now surrounded by bright pink bougainvillea, date palms and pathways laid with care.

president of the Association of Gulf Jewish Communities

It offers a tranquil setting for families to visit the final resting place of their loved ones.

But many of the graves are unidentified, leaving unanswered questions for Mr Nonoo and Bahrain’s Jewish community of about 50.

“Few people from the Iraqi Jewish community that lived here would ever go to the cemetery,” Mr Nonoo said.

“Women were forbidden from going, the reasons for which we are unsure.

“Because no one went it was left in a terrible state. It was like a jungle when my uncle passed away in 1992.

“I realised we had to start looking after the cemetery, but it remained in a bad way for some time.

“Because of the Abraham Accords, we know we will have more expatriate Jews coming to Iive in Bahrain, so we want to make sure this is an integral part of the community.”

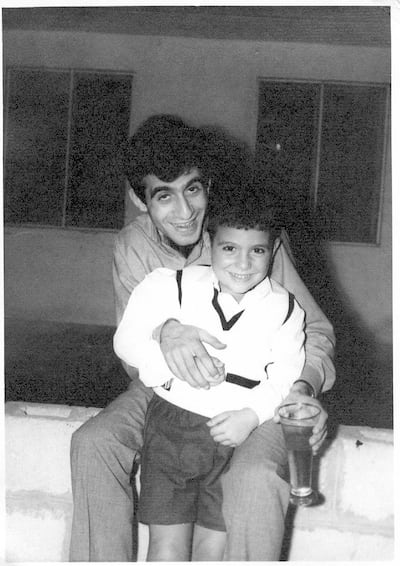

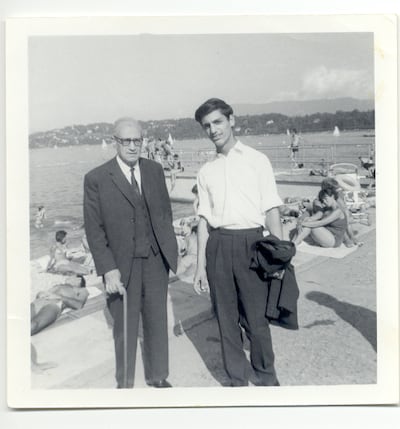

Mr Nonoo’s grandfather, Ebrahim, was born in 1897 and buried at the cemetery in 1959 and his father David was the last to be buried at the site, in 2018.

The family established the first money exchange in the country, the Bahrain Banking Company, that later became the Bahrain Financing Company.

A number of the graves, identified by oval mounds of earth and cement about half a metre from the ground, are of children who died from common childhood diseases, cholera or tuberculosis.

Others are left in sparse areas of ground, to allow room for further family graves of the generations to come.

Respects paid to community figures

One of the most prominent Jewish figures from Bahrain’s history is buried at the cemetery.

Heskail Abraham Ezra (1916-1974) was a money changer who was shot dead during a botched robbery.

He would work in the afternoons during Ramadan while his family were away in America.

It was during one of these periods when criminals entered his place of work and demanded that he open his safe. When Ezra refused he was shot and killed.

Ezra’s grave is one of the few regularly attended by his family from the US when they visit Bahrain.

Another grave is that of Joseph Khedouri (1891-1982), one of three brothers who left Iraq en route to a new life in Hong Kong.

Khedouri was so enamoured with Bahrain, he decided to stay and became one of the wealthiest men on the island through trading clothes from Europe in the 1930s.

His politician daughter, Nancy Khedouri, has been a National Assembly of Bahrain member since 2010.

Most people were buried at the site before 1960, but because there are no well-known rabbis or sages resting there it has not become a site of pilgrimage.

Dawood Reuben is buried alongside his two sons, a family of traders remembered fondly by Bahrainis for their integration into local life.

Perfume and material trader Jaqoob Yadzai (1925-2015) was the son of the first Jew to arrive in Bahrain, and is also laid to rest at the cemetery.

Celebrating Judaism in life and death

“Unfortunately, we have lost many records of who is here,” Mr Nonoo said.

“The biggest issue is how we preserve them, do we protect them with a glass frame? Otherwise they will just wither away.

“We would like to see the walls strengthened — because I’m worried they will crumble down — and the graves reset properly so they can withstand the test of time.

“Muslims go to their cemeteries regularly, but Jews are not as keen to do so and I don’t know why.

“There is a saying in Judaism, If you are born a Jew, you a die a Jew — and it is the same with Islam.

“Because of that, we believe Jews should be buried together and having our own cemetery gives us our own identity.”

Rituals run deep

Not a single Star of David adorns the walls or headstones of the graveyard, but there is a mezuzah next to a rusting gate that Mr Nonoo keeps padlocked.

He touches the small artefact containing a parchment of scriptures, reminding Jews of their duty to God, each time he arrives and leaves the gates.

His ritual at each visit is to wash his hands three times and don a traditional skull-cap on entry to the site.

Pebbles are scattered on some of the mounds, a sign the grave has been visited by family who leave a stone after each visit. Others are left unloved, and unattended.

A more unusual ritual has been costly for some, relieving them of their business, it is believed.

“It is bad luck to leave a cemetery without buying something from a shop,” Mr Nonoo said.

“There was a cold store opposite the cemetery that used to have a lot of custom from visiting Jews.

“Being at the cemetery was considered bad luck, so buying something passed that on before going home.

“The shop has been closed for a long time, so maybe the bad luck was passed on?”

The 100-year-old Jewish cemetery is alongside a Christian one and across the street from a Muslim burial ground.

A solitary Jewish grave lies inside the Christian graveyard, although it is unknown.

Just a short walk away is a synagogue, built in 1935. It was ransacked in 1948 during anti-Jewish riots across Manama.

It was left as waste ground for decades before Mr Nonoo’s father, David, rebuilt it in 1990. It was refurbished again in 2019.

From the synagogue, visitors can walk to a Hindu temple, Catholic church and mosque, an example of Bahrain’s example of religious tolerance in the Gulf.

At the height of Bahrain’s Jewish community, about 1947, there were about 1,500 Jews living in the kingdom, mainly Iraqi immigrants attracted to the island for trade in pearls and other commodities such as molasses, pottery, fabric and horses.

“At the time when these communities moved here to work, they all lived together so there was that natural level of tolerance,” Mr Nonoo said.

“They all got on well and their background didn’t matter. Their communities were intertwined and that has continued today.”