Three hours from Kolkata, in West Bengal, is Naya Pingla village, a quaint little hamlet in the lush green fields of West Midnapore. Naya is not like other villages in India, as here there are singing artists known as Patuas, who are associated with an art form called Patachitra.

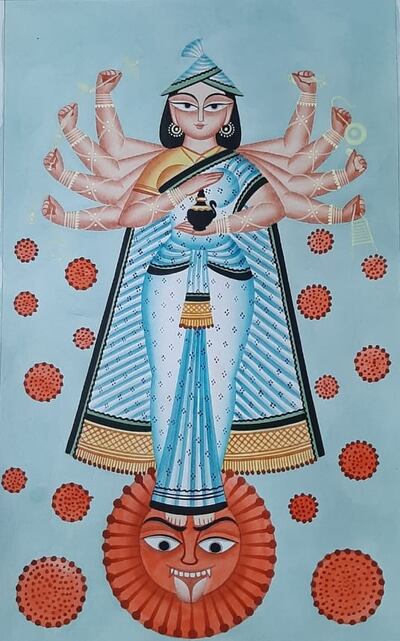

Pata is the Sanskrit word for cloth, while chitra means painting. The artists paint their stories on a long scroll that they slowly unfurl while singing.

Every wall is a canvas in this village, and everyone has the same surname – Chitrakar – which means artist. It is believed that the history of the Patua community in West Bengal dates back to the 13th century, and the art is said to be one of the oldest forms of folk painting in Bengal.

"Even though there is no written documentation of the origins of this art form, the popular legend goes that one group of painters of the Ajanta Ellora caves moved to Rajasthan, while the other group relocated to eastern India," says Moumita Kundu, the co-ordinator of banglanatak.com, a social venture that aims to support the sustainable development of the arts in West Bengal. "The eastern Indian group are the original Patuas, who traditionally sang the songs of Hindu mythology."

Patachitra is famous for its bold colours, lines and strokes. The Patuas made the paints from natural sources by crushing fruits, as well as flowers such as marigolds, turmeric, saffron and sometimes even the bark of trees. Bengal quince flower (bael) was then added to the mix to give the natural materials their vibrant colours. Surprisingly, this method is prevalent to this day.

"We insist on using natural materials in our paintings, but we use synthetic colours when we paint on T-shirts, bags or other commercially produced items," says Manoranjan Chitrakar, a resident artist of Naya. "People pay us for our work, and it would be unfair if the colour bleeds within a day."

The traditional artists of Patachitra would travel from village to village and display their arts while singing to entertain and educate the villagers on various issues. In return, the villagers would offer them rice, vegetables and other food items as payment.

artist

The Patachitras no longer travel. Instead, people from all over the world come to see their art and are delighted by the unique art form of painting-cum-storytelling through songs. But the Patuas retain the tradition of highlighting mythologies and social issues in their arts.

The government also had a role to play in the revival of the art form. The Trinamool Congress (TMC) government launched the Lokprasar Prakalpo Scheme to rehabilitate Bengal's folk art. Every artist between the ages of 18 and 60 is entitled to a 1,000 rupee (about $13) monthly retainer fee under the plan. Apart from financial help, the numerous handicraft fairs and exhibitions launched by the TMC have made the Patachitra artists of Naya Pingla very famous.

Swarna Chitrakar is an award-winning artist who has visited more than 10 countries in her career. Her art focuses on social issues, especially those suffered by women in India. "My work is mainly about the social ills that afflict women, such as child marriage, human trafficking and other issues. Although I have painted on tsunami 2004, September 11 attacks, tuberculosis, HIV/Aids and Covid-19, too," she says.

Swarna cannot read or write, so she depends on the medium of painting and singing to tell the stories in the songs. "My songs are the means through which I communicate the issues that affect us. When vaccines for coronavirus were launched, some villagers were hesitant to get the vaccines. I travelled to neighbouring villages, and I emphasised the importance of vaccination through my work to protect ourselves from Covid-19," Swarna says. Her efforts were rewarded when the villagers were convinced by her.

The Patuas have also established a painter's co-operative, Chitrataru, with the help of the NGO banglanatak.com, which has helped their work find new markets and audiences.

artist

Patuas from Naya have found a home in prestigious art exhibitions all around the world as a result of this initiative. The President's Award has been given to several Patuas from the village.

They have also participated in exhibitions, cultural exchange programmes and festivals in the US, Germany, Australia, France, the UK, Sweden, China and India. Naya is now often visited by art collectors and fans from all over the world because of their work's great renown.

But coronavirus and the subsequent lockdown in India have had a big effect on the Chitrakars.

"Neither were we able to travel to other villages to showcase our art nor did customers from outside come to buy our art," Manoranjan says. The annual Pot Maya festival, which celebrated the Chitrakars and their art, was also cancelled last year on account of the pandemic.

Although Anwar Chitrakar was troubled by the pandemic, too, he used it as a source of inspiration for a new exhibition.

Anwar grew up in the village of Naya, and although he had an interest in painting, he initially took a job as a tailor to ensure his family's security. Then he came up with the idea of making his own paintings, with a twist. As a self-taught artist, his work covers a wide spectrum of subjects, from the depiction of classic figures such as Radha and Krishna to more contemporary issues such as the Saradha fraud and the Maoist insurgency.

"So, regardless of whether or not they [visitors] buy it, they'll see it as a unique piece of art. That's what I had in mind when I started," Anwar says.

As a result of the coronavirus shutdown, he was unable to concentrate on his regular work, "so, I decided to come up with something that would make people pause and reflect".

To express the weird and transitional nature of the lockdowns, he began painting a sequence of 13 works. This was a solo exhibition on the Emami Art Gallery website, titled Tales of Our Times, in July 2020.

The police in one of them are angry because there are no automobiles on the road and they cannot accept any bribes, he says. His work reflects the positive effects on the environment throughout this period, as well as the loneliness, boredom and hope for a better future.

"In Patua art, it's always this way. It's not unusual for the Patuas' work to be influenced by major world events and social issues, as well as by our desire to spread a positive message for the development of society," Anwar says.

When the artists had very little work during the lockdown, Manorajan and a few other Chitrakars from Naya were enlisted by MeMeraki, an online art workshop platform. "I wasn't even aware that online classes could be held, and it has turned out to be a boon for us during the pandemic," Manorajan says.

But online classes aren't enough. Manorajan hopes that in the future, the government will allow special loans for Chitrakars so that they will be able to buy paints for producing T-shirts and tote bags, for example, with their trademark style of Patua painting.

"The synthetic paints cost a lot, and we require a lot of it to produce one painting. I hope the government recognises our pain and helps us during this time by organising more fairs and exhibitions, and giving us special loans."